Film Fatale: Picnic at Hanging Rock and Australian Gothic

Words: Charlotte Amy Landrum

When a young British adult reaches their confused and existential mid-twenties, they are taken into a room with three doors. One door leads to Southeast Asia, where they can seek spirituality and become an influencer. Another leads to a newly built house in the Midlands with a decent mortgage, where they can raise some children and tend to their BMW. The final door—one that is almost falling off its hinges due to mass use—leads to Australia.

I have never been to Australia. It is one of those places I can’t envision when I close my eyes, like trying to imagine the universe's beginnings or the fourth dimension. It sits there in all its hugeness, yet 95% of its land is unoccupied due to the harsh landscapes where only people willing to learn how to self-sustain, or some indigenous communities, reside. It is so far away from England but supposedly so similar, and many say better, and everyone manages to look past the snakes.

With that said, if you’re a non-Aussie and want to try to understand the place without the long-haul flight, then I recommend sitting down and getting into Australian New Wave cinema: a period from the 1970s to mid-80s where filmmakers, both local and not, braved the Outbacks to try and decipher the experience of living there.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

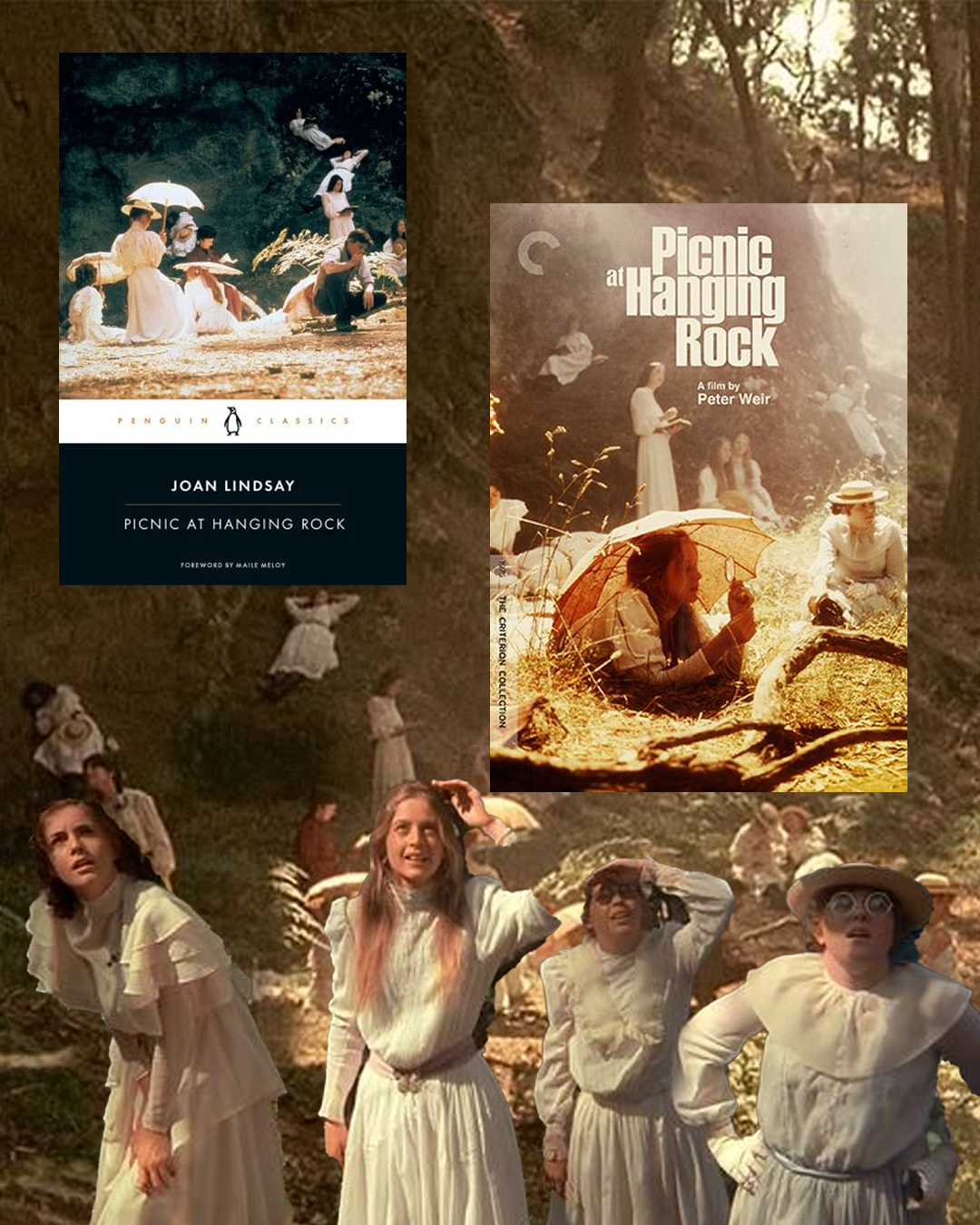

One of the most notable films from this movement is the coquettish and sweaty Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), directed by Peter Weir. Based on the novel by Joan Lindsay, the film takes us to rural 1900s Victoria on Valentine's Day, where we’re introduced to the girls of Appleyard College. Inside the walls of the prestigious school, the students are draped in white gowns, wash their faces with bowls of water scented with flower petals, and comb their long silky hair with ornate brushes whilst softly singing. They are getting ready for a day out at Hanging Rock – a looming geological formation that towers above the surrounding desert and is, even at first glance, an interesting choice for corseted ladies to picnic. It’s almost unsurprising, then, when three of the students go missing after travelling up the rock in a hazy and trance-like state.

“The contrast between the ill-prepared British person and the natural land is the biggest recurring theme in Australian New Wave Cinema.”

Throughout the entire film and before students Miranda, Marion, and Irma vanish within the crevices of Hanging Rock, it is clear that the English girls of Appleyard College don’t belong here. In layers of Edwardian garments under the beating heat, we can almost feel the thick and unforgiving air beam off our screens. The girls’ picnicking accentuates this – they are embarrassingly trying to uphold activities that would ideally take place on a lazy 20°C day in an English garden. But this is not a pleasant late-spring lunch in Hyde Park; this is the burning slopes of Victoria. The disappearance of the three girls that follows feels like the land biting back at its British colonisers, throwing the unprepared upper class folk into a manic frenzy to try and understand this fever-dream mystery. (Spoiler: they never do.)

The contrast between the ill-prepared British person and the natural land is the biggest recurring theme in Australian New Wave Cinema. Alongside Picnic at Hanging Rock are two other essential movies: Walkabout (1971), directed by Nicolas Roeg, and Wake in Fight (1971), directed by Ted Kotcheff. Walkabout and Wake in Fight bring being in places you shouldn’t be to the forefront. Walkabout follows two English children stranded in the desert but ultimately saved after meeting an aboriginal boy with the survival skills to hunt, find water, and show them the beauty of the land that lurks outside their city. Wake in Fright is a 10/10 film that follows a preppy English school teacher embarking on a menacing bender with small-town locals that shatters his moral compass.

Despite these three films taking place in different decades with varying tones, they all tell their stories through the same language of contrast. Here is a shot of a poisonous snake and then a private school child; a shot of a sparkling, advert-worthy Sydney and then a shack surrounded by slaughtered Roos; a bustling financial district and then the bare, dead landscape.

These films make me think of Southern Gothic – another genre that explores a land that outsiders flippantly decided to call home. Whilst the historical and present horrors of racism and colonisation that the American South (and America as a whole) has seen shouldn’t be compared to anywhere else, the films that were created to express the ongoing experience of a land and home being warped, destroyed and feared by newcomers who gleefully settle there is ever present when looking at Southern Gothic works like Daughters of the Dust (1991) or even season one of True Detective. In the same way, in these Australian films, these environments are expected to accommodate the masses despite a cruel history and a natural landscape perceived as uninhabitable by many without the dry blast of an AC unit and their personal home comforts.

Of all the scenes depicting the hot sun beating down on the clueless Brits in these films, a moment in Picnic at Hanging Rock encapsulates it all perfectly. During their carriage ride to the Rock, the girls’ teacher, Miss McCraw states: “This we do for pleasure, so that we may shortly be at the mercy of venomous snakes and poisonous ants. How foolish can human creatures be?” Moments later, one of the children mumbles to herself in the same carriage: “Waiting a million years, just for us…” as she gazes out the window, not knowing the tragedy that awaits, with an attitude of invincible reassurance despite all the environmental odds stacked against them.

These films all showcase the faults and vulnerabilities of a Brit Down Under, but in general, the works that came out of the Australian New Wave more importantly highlight the unique beauty of the country. Walkabout shows us glistening springs through the eyes of adolescents, Picnic at Hanging Rock evokes the same feeling of laying on a soft bed with pink sheets during a July heatwave, and even Wake in Fight kind of makes me want to hang out with some fellas, do some gambling and slam some beers (only for one night though, not five like in the film). These stories make you feel a similar way to Miss McCraw sitting in the back of the carriage: aware of how unprepared you are, but willing to go all the same just so you can sit in the warmth next to a huge rock with only your dumb faith in between you and the vicious sun.