Why Women Are Drawn to Work Culture Television & How Severance Subverts the Genre

Words: Lexi Covalsen

Make it stand out

For decades, television about work culture has provided a space for women to explore themes of ambition, independence, and identity. From Marlo Thomas’s Ann Marie, who twirled in excitement at the mere prospect of having a temp job in the 1960s sitcom That Girl, to Sarah Jessica Parker’s chaotic Carrie Bradshaw being mocked in the opening sequence to Sex and the City – as the glossier version of her “work self” vamped by on a bus billboard, splashing the real-life Carrie with gutter water – TV has long asked whether women really can have it all.

The iconic working girls of television have been the conduits through which women have asked the pressing questions of our times: “What might it look like to work outside of the home?” And “can professional fulfillment ever take the place of romance?”

For the 2020s, however, those archetypes – the secretarial sweetness of Ann Marie and the disillusioned frothiness of Carrie – have come to die in Helly R. (Britt Lower), the female lead in Apple TV+’s dystopian workplace drama Severance, who simply asks: “How the fuck do we get out of here?” ‘Here’ being the suffocating prison of corporate work culture.

“Social Media Guru,” “Innovation Catalyst,” “Solution Provider,” “Macrodata Refiner.” Are these job titles really all that different? For those uninitiated, I would be surprised if you could pluck out Helly’s job title from that list of real life LinkedIn offers.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

In an increasingly digital world, our jobs have decreased in significance while eating up more and more of our lives. The expectation for one’s job to reflect their inner truth is at an all-time high, while the reality of corporate work is not far off from the nonsense clicking that Helly does day-in and day-out at her cell-like desk.

Let me take a step back, though. You see, Severance is the story of a ragtag group of desk-workers employed by a biotech company called Lumon. These employees have all opted to undergo a radical procedure that separates their work selves (innies) from their outside selves (outies), effectively creating two distinct identities. It’s a chilling Black Mirror-esque universe where the question of work-life balance is taken to the extreme.

The second season, which premiered in January 2025, has already been hailed as the heir-apparent to the prestige television throne, following in the footsteps of workplace dramas like Succession, Industry, and Mad Men. The show’s protagonist is Mark Scout (Adam Scott), a grieving man who chooses to undergo severance to escape his pain, at least for part of the day. Alongside him are his colleagues – Irving (John Turturro), Dylan (Zach Cherry), and micro-bang icon Helly.

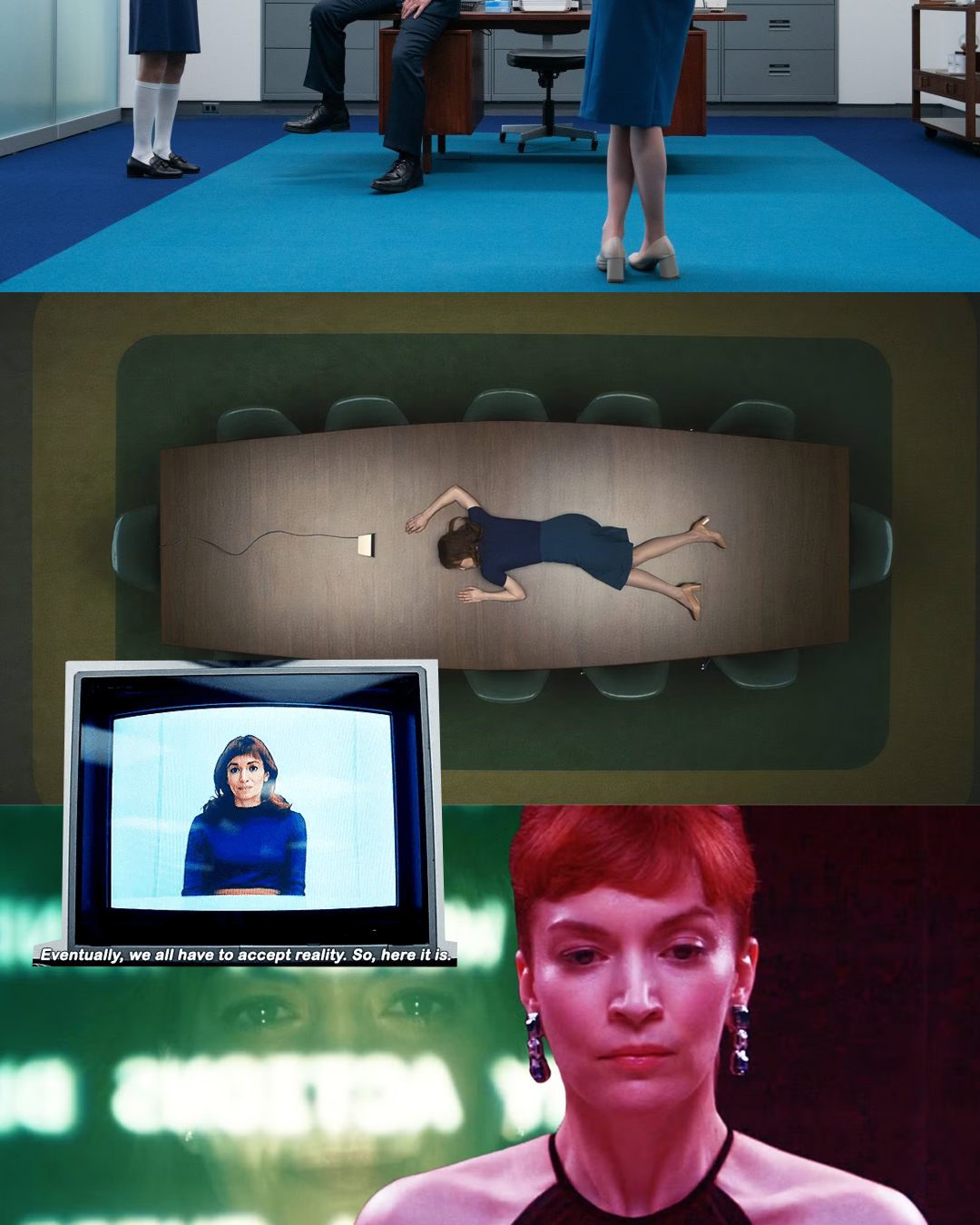

We meet Helly, our lone female worker, sprawled belly-down on a conference table in Episode One. This is the moment of her innie awakening. Unlike her male coworkers, dressed in drab, unflashy suits, Helly’s wardrobe of marble blues and mellow yellows subtly nods to the flower-power aesthetic of That Girl. If it weren’t for the computer screens, you might think she woke up in 1966 after all.

“In an increasingly digital world, our jobs have decreased in significance while eating up more and more of our lives.”

But unlike Ann Marie, Carrie, or any of the career women before her, Helly isn’t climbing the corporate ladder – she’s trapped by it. Before long, she’s actively resisting the severance process, trying to escape the fluorescent-lit, windowless offices of Lumon through a series of increasingly gory acts of self-mutilation. Anything to feel the sun on her skin.

She starts by writing desperate notes on her arms in ink and then progresses to threatening to cut off her own hand (the symbolism is thick…). Finally, a glassy-eyed Helly’s final attempt at freedom is by hanging herself from an extension cord in the all-powerful office elevator. The result? You guessed it, she’s saved just in the nick of time: resuscitated, rebuked, and swivelled immediately back to her desk.

But why focus on Helly R.? She’s not the protagonist. Yet, as the only woman in the office, she bears the weight of history. She symbolises more than her male counterparts. In her, we can see how the fantasy has finally come to die – the one that our grandmothers believed when they saw Marlo Thomas strutting out of the elevator in her mod dresses and pearls, and the one we ourselves believed not that long ago, flaunting #GirlBoss mugs and bumper stickers. That notion – that promotions, paychecks, and corporate gains would free us from the shackles of patriarchy – has shattered. In 2025, women still earn 13.1% less than men in the UK, reports of workplace sexual harassment are rising, and only 1 in 10 of the country’s top companies have a female CEO.

Perhaps in response to this, the online landscape is both regressing and becoming more and more confusing: we are constantly being bombarded with conflicting content about work. “Day in the life as a stay-at-home girlfriend” videos live side-by-side with “office siren” get-ready-with-mes and “get your money up” reminders. But beneath the surface, these warring trends are nothing more than distractions from a capitalist world that demands you perform for profit while suppressing every other facet of your humanity. In the end, we’re all on some level just refining macrodata, and Helly R’s wit and constant defiance is the antidote to this mind-numbing reality.

This is the real triumph of Severance. It’s not just the plot’s mystery-box appeal that keeps us coming back (what kind of company even is Lumon anyway?), but it gives us the chance to exorcise our feelings of alienation – the creeping unease, the loss of control, the haunting thought that maybe work really is all there is. Maybe the real reason we keep watching week after week is that, deep down, we believe that if Helly R. can escape, maybe we can too.