The Forever Politics of My Beautiful Laundrette

Queer cinema, as a cultural arts movement, is inherently political. The sheer nature of an LGBTQIA+ production is definitive of intense dissatisfaction with the status quo in which said film presents itself. Indirect or not, queer cinema has always been adamant in its attempts to illustrate social injustices through narrative storytelling and revolutionary foregrounding of its subjects – whether a justified attack on the workings of a right-wing autocracy, or the fragile heteronormative understandings of gender and sexuality.

Radically demonstrated by the commentaries of America’s breakthrough New Queer Cinema movement (term coined by B. Ruby Rich), since the 1990s said movement has characterized itself with the rejection of heteronormativity and championing of outcasted individuals of colour, transgender performers, and gender non-conforming citizens. Without New Queer Cinema, we as an audience would never behold the likes of Paris Is Burning (1990), Tangerine (2015), and Moonlight (2016).

In contrast, British queer cinema in the late 20th Century was unsurprisingly dominated by conventional, melodramatic storytelling chronicling the plights of the white, privileged middle-class gay male – an unfortunate trope which continues to dictate much of Western filmmaking. Whilst the touching, introspective works of artistic greats such as Derek Jarman and Isaac Julien invoke an alternative poetic cinema, the earliest precursor of a marriage between mainstream cinema and the inclusive identity politics of New Queer Cinema is undeniably that of the Academy Award-nominated collaboration between screenwriter Hanif Kureishi and director Stephen Frears titled My Beautiful Laundrette (1985).

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Bearing the title of ‘most rewatched LGBTQIA+ film’ in my Letterboxd catalogue (2014’s Pride a close second), My Beautiful Laundrette is, in my opinion, the quintessential darling of British queer cinema. Although white-centric Hollywood successes such as Call Me By Your Name (2017) and Love, Simon (2018) have recently shocked and provoked the homophobic masses, such mainstream productions are saturated and tame by comparison - even Pride. My Beautiful Laundrette does not shy away from its subject matter – so unapologetic in its depiction of same-sex interracial romance and gay sex, in fact, that it is astonishing how protests from the right-wing resided primarily in newspaper columns and not the streets. Nevertheless, 37 years later it sparks conversation and debate.

Financed by a fresh-faced Channel 4 looking to appease the interests of frustrated voiceless minorities, the understated comedy-drama depicts the south London tale of effervescent second-generation Pakistani immigrant Omar, played by the dashing Gordon Warnecke, determined to exceed a life of poverty. Tasked with the renovation of the dilapidated “Churchill’s’ Laundrette”, owned by Thatcherite uncle Nasser (Saeed Jaffrey), Omar navigates an alien world of 1980s enterprise rife with the typical racial harassment, class stratification and economic upheavals familiar to him. But of course, who is to blame for such difficulties other than the conservative administration and agency of ex-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (ding-dong, you know the rest).

As detailed by historian Peter Jenkins, Thatcher “labelled England as sick – morally, socially and economically”. Attributing said ‘fall from grace’ to the liberalisation of the arts and the legalisation of homosexuality, a new Thatcherite agenda rested upon the entrepreneurial endeavours of wealthy yuppies, the foundations of a new national economy rooted in the nuclear heterosexual family unit indicated the beginning of a homophobic reign of terror. This subsequently peaked on 24 May 1988 with the now-abolished discriminatory Section 28 law coming into effect, banning the “publication and promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities at the height of the devastating AIDS epidemic. Remnants and repercussions of Section 28 still echo today. In British schools, for example, with GAY TIMES reporting “half (48%) of pupils have had little to zero positive messaging about LGBTQ+ people” as of 2020.

Contesting Thatcher’s ludicrous policies and rhetoric, the provocative Kureishi and Frears envisioned My Beautiful Laundrette as a well-observed, quick-witted state-of-the-nation film explicitly illustrating the socio-political pressures and dreary realism of a country in crisis. Deliberately the focus, they subvert racist cultural stereotypes and foreground Thatcher’s new economic order by positioning the community of middle-class South Asian diaspora as ironic allegory. Thriving in the entrepreneurial age of Thatcherism, the likes of Nasser and hedonistic business partner Salim (Derrick Branche) coexist in conflict amidst an unemployed underclass of British natives.

However, it is the intense scene-stealing chemistry between Omar and squatter Johnny as two gay male lovers, portrayed by a young Daniel Day-Lewis sporting frosted tips and a cockney accent, which breaks the mould.

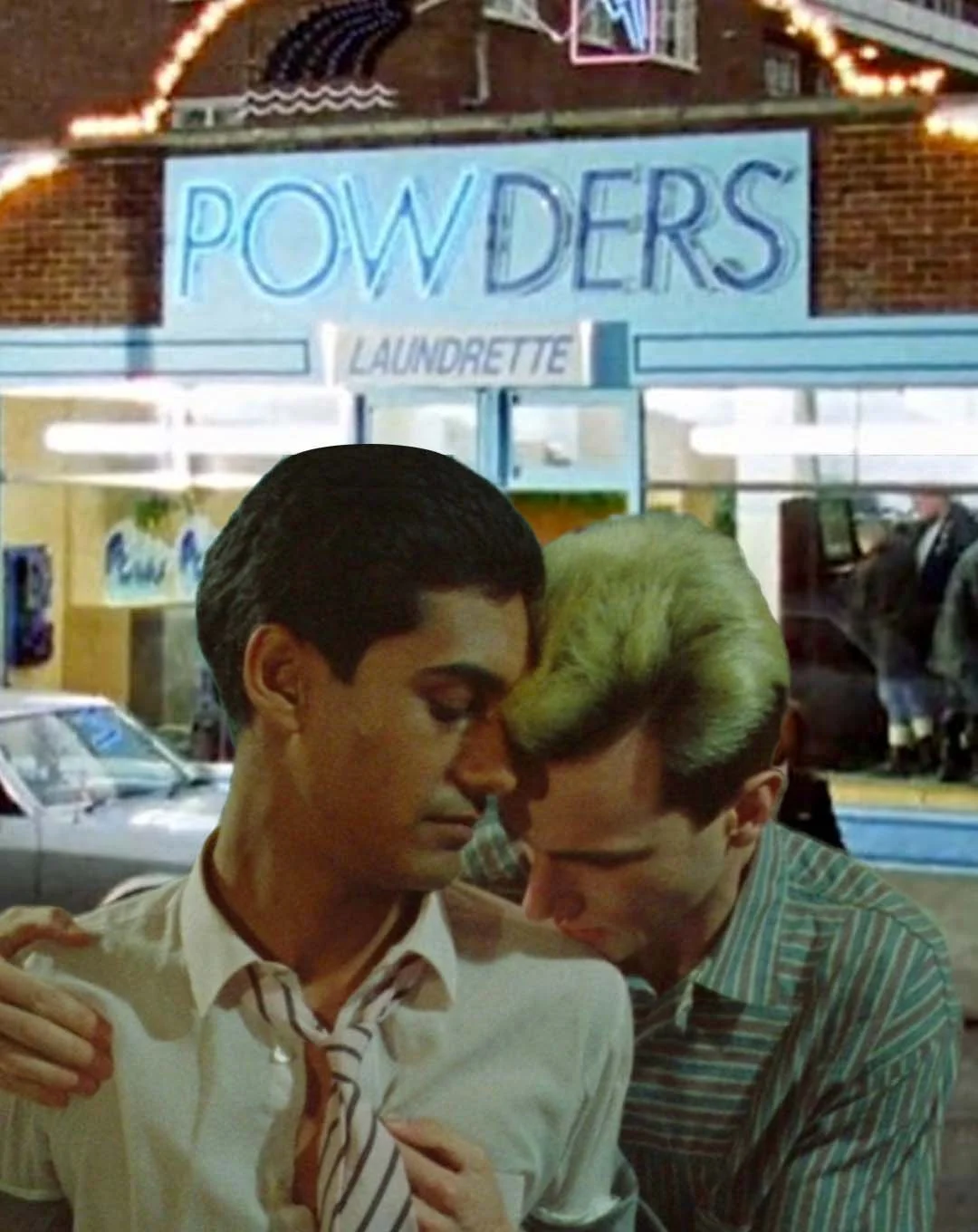

When reunited with his estranged childhood friend, Omar hires Johnny to help him renovate and run Churchill’s. Anyone familiar with the existence of My Beautiful Laundrette can conjure up the image of Johnny discreetly licking Omar’s neck, hidden in plain sight from National Front fascists. Trust me, it’s one for the queer history books. Despite the film’s repetitive attempts at homoerotic subtext and gay innuendo, the topic of homosexuality itself is remarkably inconsequential. In the oppressive political climate of My Beautiful Laundrette, the larger issue at hand is one of enterprise - Thatcher’s beloved. With erotic, organic scenes of sexual contact abound, one particularly intimate moment sees Johnny sensually pouring champagne from his mouth to Omar’s mid-intercourse in the dimly lit office of the laundrette.

“With all this evidence, it begs one final question. Is present-day Britain all that different from the decadent eighties?”

According to critic Alexandra Barron, this chain-of-events sets into motion the fantasy of a new “queer national romance” focusing on the same-sex romantic union of Omar and Johnny as star-crossed lovers, representative of the uniting of rival factions within a narrative strategy – the safe space of the now “Powders” laundrette, transformed from graffiti-loaded squalor to feminized utopian artifice. Assuming joint-leadership roles, much like the unlikely partnerships of Pride, our protagonists are ultimately responsible for the merging and eventual hybridisation of two opposing communities in a “spirit of trust and collaboration”, prospering from the benefits of their private enterprise built on sexual diversity.

During climactic final scenes in which Salim is brutally attacked by fascist skinheads, Omar and Johnny pass the crucial test of the crossing of ethnic boundaries. Left bloody, Johnny manages to save Salim from being beaten to death. Whilst Omar nurses Johnny, exclaiming “you’re dirty, you’re beautiful” in a final act of oxymoronic protest against the right-wing, the film closes with the two of them shirtless - playfully splashing each other with water from a sink.

By the 21st Century, My Beautiful Laundrette had already solidified itself as a bona fide classic of British queer cinema, topping curated film lists by the BFI and Advocate. It continues to resonate with an overwhelmingly positive South Asian queer diaspora – Trikone magazine stating “the kiss between Johnny and Omar has, to many a queer South Asian, become the moment they came out to themselves.” But in the contemporary political climate of 2022, are the socio-politics of My Beautiful Laundrette still relevant? By the looks of recent immigration removal and cost of living protests, it certainly seems that way. Our current Tory government persists on stalling the banning of conversion therapy with the inclusion of transgender individuals, beside a refusal to reform a now outdated Gender Recognition Act. Meanwhile, police delays over a recent spike of unwarranted violent homophobic hate-crimes are disturbing LGBTQIA+ communities across the nation. Above all, enterprise continues to dictate.

With all this evidence, it begs one final question. Is present-day Britain all that different from the decadent eighties?

Words: Douglas Jardim