The Algorithm Isn't the Problem - It's the People Behind It

Make it stand out

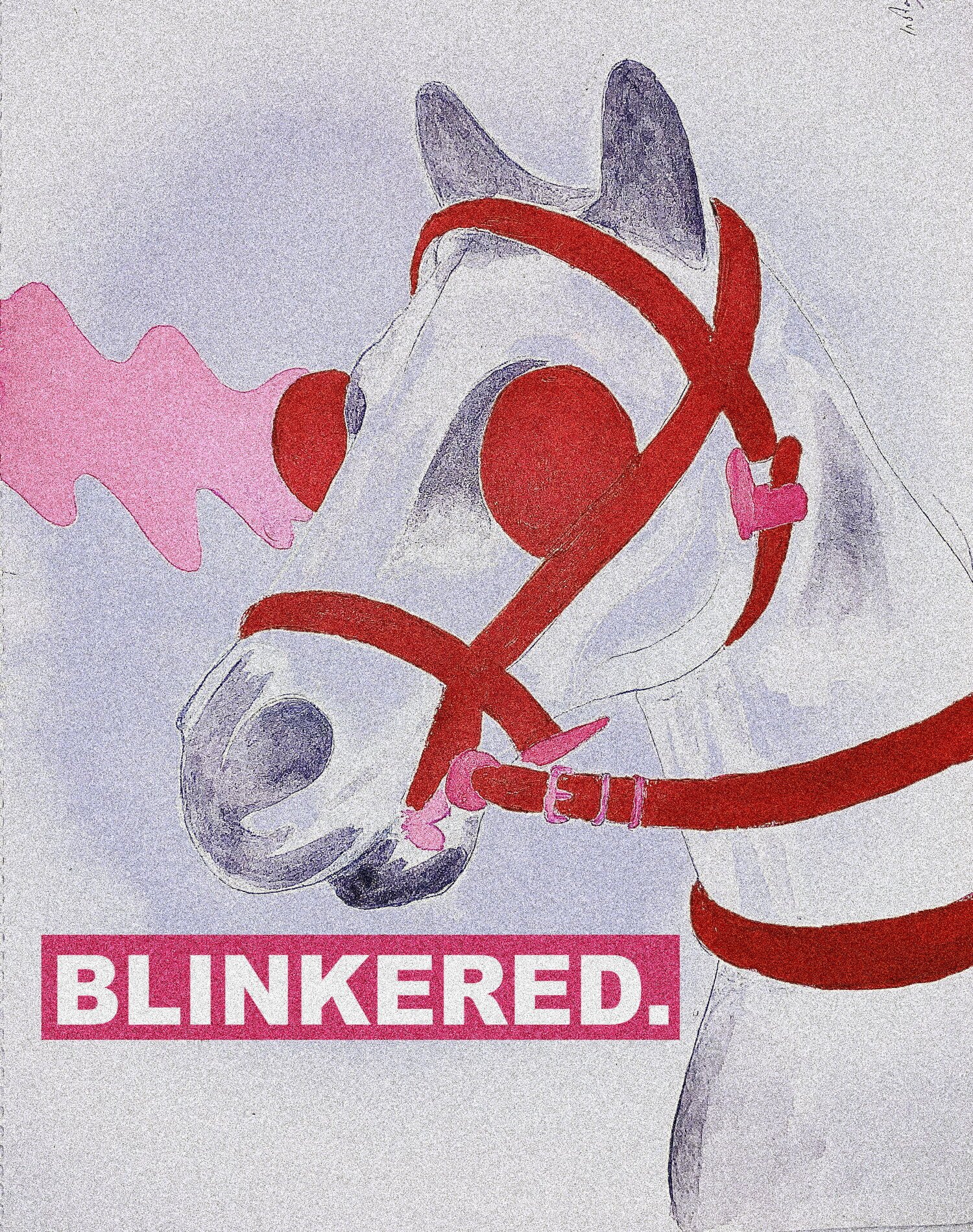

The algorithm is the perfect enemy. A faceless entity upon which to project all our collective anger for the wrongdoings of the internet, or at least most social media. Has your picture featuring a bit of nipple been deleted? The algorithm’s fault. Has one of your favourite accounts been shadow-banned, so you now no longer see their content? The algorithm’s fault.

What does worry me is the ease at which we blame our issues with social media— especially Instagram — on this omnipresent algorithm, and whether this prevents us from getting to the root of the problem. As defined by Jamie Bartlett in his book The People Vs Tech, algorithms are simply a ‘mathematical technique, a set of instructions that a computer follows to execute a command which filter, predict, correlate, target and learn’. In other words, they’re benign mathematical processes. It’s not the algorithm itself that is the issue. The problem lies in how they are designed and deployed, and by who.

While algorithms are key to implementing the censorship of marginalised communities, they aren’t wholly responsiblefor it. Anger at the algorithm misplaces the blame for their malfunction onto a mathematical process rather than those who are responsible for writing them — and the community guidelines they adhere to. To create real change, this frustration needs to be developed. The anger that we place onto the algorithm should instead be directed towards the software developers and coders creating these programmes. They’re the ones who have the power to change how they function.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Marginalised voices in the LGBTQI+ and sex worker communities have raised the issue of being censored by Instagram despite adhering to community guidelines. Recently, Pxssy Palace, a queer arts collective who also run club nights, have spoken out about having their Instagram content shadow banned. Ruby Rare, a sex educator, and NYC based musicians Sateen have both previously had their Instagram accounts deleted. Often this censorship is justified by Instagram claiming that the accounts in question have violated the terms of service by posting nude or sexually explicit content. Yet an investigation by Salty into algorithmic bias in content policing on Instagram confirmed the suspicions that ‘women, trans and nonbinary people, BIPOCs, plus-sized people and sex workers are being silenced, by conscious or unconscious bias built into the framework of our digital world’.

Through a survey to their followers they found that:

- Queer folx and women of colour are shadow-banned and have their posts and accounts deleted at a higher rate than the general population.

- Among their data set, there was a high number of accounts that were reinstated after deletion showing a high rate of false flagging.

- Plus-sized and body-positive profiles were often flagged for ‘sexual solicitation’ or ‘excessive nudity’ despite their posts being of a non-sexual nature and adhering to community guidelines surrounding nudity.

There can be little denying that algorithms are actively policing marginalised voices by projecting the rules of a social network through its millions of members; but the central issue here is Instagram’s patriarchal attitudes towards bodies and sexuality. This results in the fetishisation of some bodies over others, and the regulation of sexuality so that it aligns with an ‘acceptable’ form. As a result, the prohibition of nudity and sexually explicit content by the algorithm seems to be not a blanket ban. But rather a ban of nudity and sexually explicit content they deem to be unacceptable, and therefore undesirable.

If there were a total ban on nudity and sexually explicit photos, then surely images of slim, young, predominantly white, able-bodied women, such as those posted by companies like Victoria’s Secret, would be subject to the same scrutiny as those posted by marginalised communities? Simply, they aren’t. This is because — in addition to the many intersecting privileges the typical Victoria’s Secret model possesses — these images are produced for the consumption of men.

In such images, the women are shown in their underwear but are voiceless, sexually suggestive whilst showing none of their own sexuality. They embody the patriarchal dream woman who is simultaneously sexually available yet innocent, miraculously tiptoeing between the dichotomies of the madonna-whore complex. This strengthens the pre-existing notion that “women cannot be sexual beings in the way that men are” — that they cannot be agents of their own sexuality, and that it must be controlled by men. IRL this has been done through restricting access to contraception and abortion, Female Genital Mutiliation, and historically sending women to asylums for ‘hysteria’ due to thier sexual desire. Algorithmic bias just means that this control of sexuality has been extended into the online realm, but the regulation of sexuality into an acceptable and consumable form for cisgender heterosexual men is nothing new.

The desire to control forms of sexuality that do not exist primarily to serve cisgender, heterosexual men can also be seen with the censorship of LGBTQI+, body-positive and sex-positive accounts on Instagram. These accounts raise the visibility of alternative forms of sexuality and ways of relating to the body that threaten key elements of patriarchy; from the dominance of heterosexuality, the demonisation of female sexuality and strict beauty standards. It’s unsurprising, then, that these accounts undergo a higher level of scrutiny from the Instagram algorithm. They represent a threat to the patriarchal ideals that we live under; and are seen as being ‘unacceptable’ because of this.

Yet, as well as being censored for failing to align with patriarchal views of sexuality, other accounts are also censored because of the patriarchy’s extreme sexualisation of certain groups. As mentioned earlier, women of colour are policed at a higher rate than the general population and plus-sized bodies and body-positive profiles are flagged for ‘sexual solicitation’ or extreme nudity. Despite the images posted not being of a ‘sexually explicit’ nature, the fetishization of marginalised bodies under the patriarchy deems these images as being more sexually explicit than images of privileged bodies. They are seen as less acceptable and more taboo because they do not adhere to strict patriarchal beauty standards. As a result, these images are more heavily censored.

The issue of algorithmic bias and censorship of marginalised communities can’t be viewed as simply the algorithm’s fault. Instead, we must view algorithms as an instrument in implementing patriarchal views in the online world, and work to prevent this.

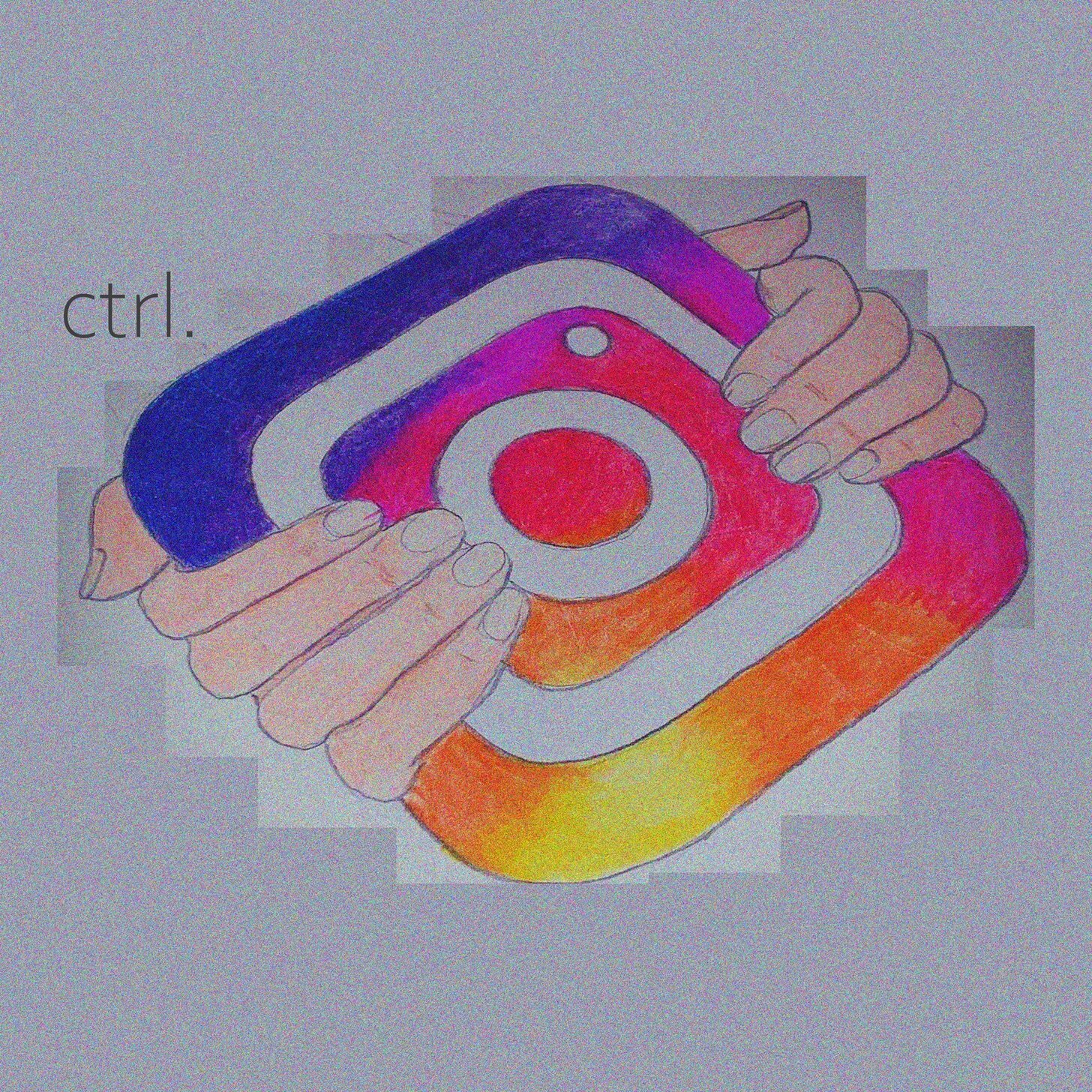

How can we expect our social networks to equally represent people when they are still overwhelmingly designed and engineered by straight white cisgender men? In Facebook’s 2018 diversity report, it was shown that in the technical field, only 22% of employees were women, 1% were black, 3% were Hispanic and, while there was no data on LGBTQI+ employees in technical roles in the US, only 8% of employees self-identified as LGBTQI+.

In addition to this lack of diversity in employees, it showed there was a lack of cognitive bias training, although there was often training managing overt bias to help with issues of diversity and inclusion. Cognitive bias is the often-subconscious biases that we hold which affect our ability to judge and objectively make decisions. An understanding of this is important, as although algorithms themselves are mathematical processes, cognitive bias from those engineering them has the potential to seep in, and are then deployed across an entire network. Moving forward, it is important that the people who design and maintain our social networks are both diverse in makeup and aware of their subconscious biases, so that social networks can become places of equality and justice.

Our online spaces don’t have to be condemned to a patriarchal future, and with increased diversity in those who design algorithms, increased understanding of cognitive bias by tech companies, and increased work to tackle wider societal bias, this level of censorship could become a thing of the past.

As well as increasing the diversity of those who work in tech and their understanding of cognitive bias, an increased awareness of the pervasive influence of the patriarchy in all areas of life is needed to ensure that it doesn’t continue to permeate our online worlds. The irony is that, in the present moment, the accounts that are doing the work of educating people about the patriarchy are the ones being censored in the online world. As a result, their activism isn’t having the impact it should.

Algorithms are simply instrumental extensions of the patriarchy into the digital realm. By all means be angry at them. But don’t lose sight of the attitudes responsible for censorship in our online world. The algorithm is the perfect enemy, because it distracts from the real bad guy which is, as always, the invisible and insidious structure of patriarchal values that govern the world we live in.

Words: Issey Gladston | Illustrations: Zia Larty-Healy