“I Am No Better Than a Man” - Where Has Female Desire Gone?

Words: Laura-Ashley Modunkwu

Make it stand out

Meme culture functions as a photo album, chock-full of snapshots of our collective psyche. With the meme’s unique ability to humorously and succinctly capture contemporary discourse through a few words or an absurd photo, new jargon is born. The “I am no better than a man” trend is no different. While its origins are murky, the joke speaks loudly to all that goes unsaid about how we discuss gender and desire.

This playful confession is often sparked by a new photo dump of Megan Thee Stallion on Instagram or a fan edit of K-pop idols. Simply put, it's another way for us to laud female desirability. A paradox anchors the humour here: despite decades worth of campaigning against objectification, maybe, just maybe, women, too, harbor a mischievous, internalised voice whispering impure thoughts about our fellow women into our minds. It’s all relatively harmless, and perhaps by specific standards even an empowering admission, this silly public acknowledgment of women’s capability to lust just as men supposedly do, the shameless desire of it all.

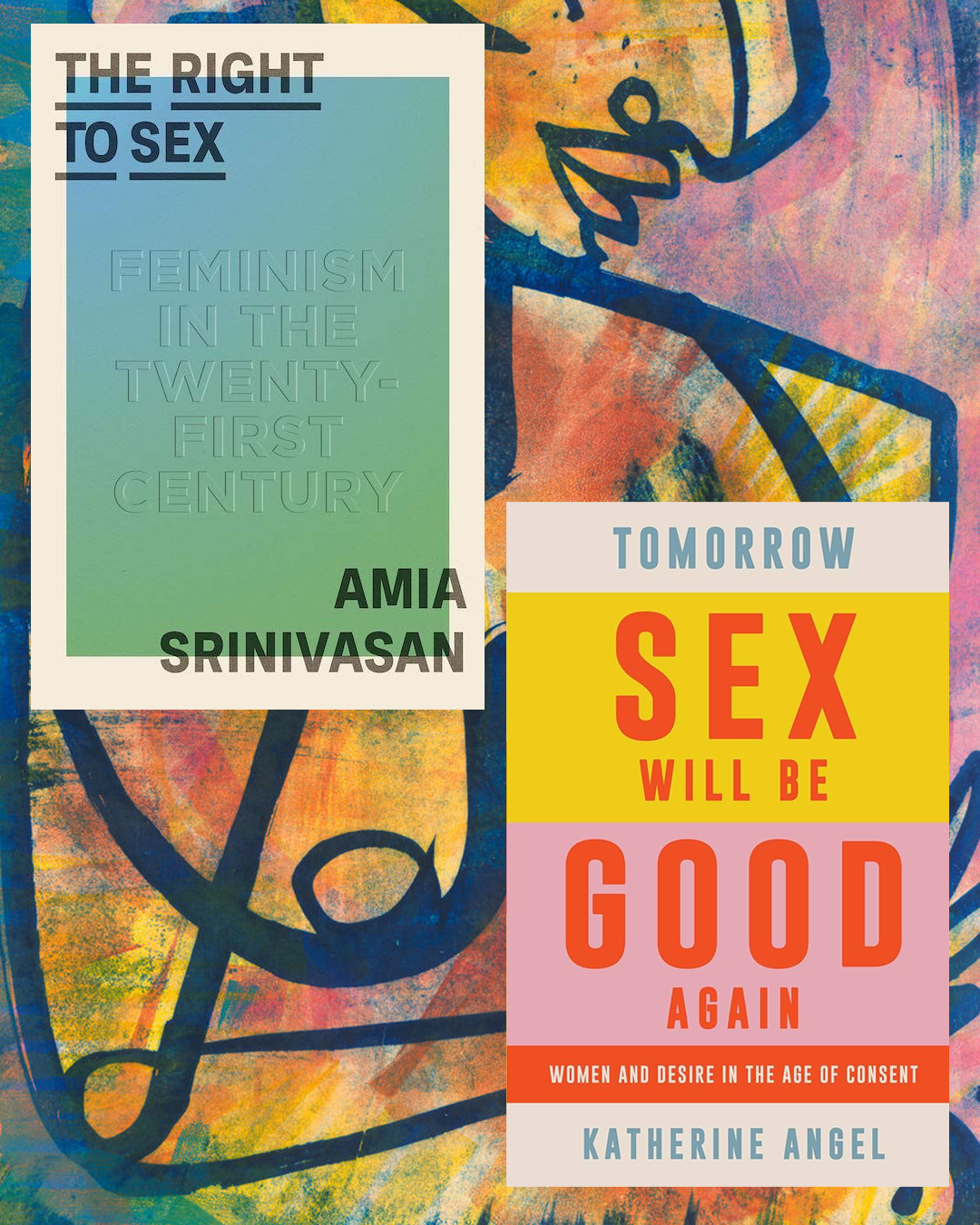

We’re also aware of the paradox, however: what appears liberatory on the surface is often hiding a trap disguised as freedom. Those of us who belong to and advocate for marginalised groups are not exempt from inadvertently reinforcing the very systems we aim to dismantle, frequently reshaping familiar power dynamics into a more polished and socially acceptable guise. Katherine Angel explores this contradiction in her book Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again: Women and Desire in the Age of Consent, exploring how female expressions of desire are often twisted against women, warning against the notion that true sexual liberation lies in adopting the same frameworks of power that have long oppressed us, particularly if we mirror men.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

This mindset arguably stems from a particular brand of sex-positive and pop feminism that shaped the 2010s. Many millennial feminists, drawing inspiration from the second wave before them, sought to reinvent female sexuality with the seemingly radical declaration that women enjoy sex “just as much as men.” Inadvertently this approach, while well-intentioned, reinforced the heteronormative and patriarchal sexual dynamics it sought to dismantle. Instead of interrogating why cishet male sexuality stood as the ideal, it only helped to entrench that standard further. In an attempt to establish a new status quo where women are equally as desirous and uninhibited, women were still being encouraged to operate under a framework that positioned male desire as default.

Gen Z, the generation so often dismissed as “sex-negative” and puritanical, are simply struggling to navigate a warped, inherited sexual landscape. Their efforts, upheld by a growing population of progressive women, are clear in calls to “decentre men,” “reject the male gaze,” and completely disavow heteronormativity.

Gen Z, therefore, is trying, however messily, to carve out new paradigms of attraction, pleasure, and power. Amia Srinivasan aptly asks in The Right to Sex, “If my desire is to be disciplined, who will do the disciplining? And if my desire refuses to be disciplined, what will happen to me then?”

“ For centuries, female sexual desire has been pathologised and policed, and this history of stigma lingers today.”

Heterosexual women are not alone in this reckoning. Among sapphics, there seems to be a notable rise in discourse critiquing the forced sanitisation of lesbianism and its prescription as the “purest” form of love due to its absence of men. This form of diet-political lesbianism has aligned sapphic sexuality as inherently more ethical or politically correct and, in its valorisation, has been led down the plank to be stripped of its complexity, a complete flattening into something palatable, restrained, and desexualised. The romanticisation of lesbianism as the ultimate moral alternative to heterosexuality has led to a sanitised perception of queerness that draws the line at femme for femme attraction as this is widely more accepted than butchfemme dynamics.

The crux of the issue here isn’t simply that women feel the need to defer to male sexuality as the standard; it’s the nature of the standard itself. We’re in a time where male sexual entitlement, through blatant displays of power like catcalling, groping, staring, and verbal sexual harassment are on the rise, used for popular entertainment, and, if jokes online are any indication, becoming coveted as a positive gender affirmation. Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic speaks to how we’ve been conditioned to both fear and misunderstand the erotic, a distortion that has been weaponised against us. Meanwhile, pickup artists and bio essentialists alike argue that men are “wired” this way, urging women to adopt their playbook. This warped perception of desire has left us confused about what genuine sexual agency looks like. What we often interpret as male "sexual confidence" is, more often than not, just the unchecked exertion of power.

“I’m no better than a man” can honestly be understood as young women testing the boundaries of desire while still maintaining some plausible deniability through their humour and giving themselves a kind of leeway to engage with their sexual impulses in a way that feels safe, as well as shrouding the implications and assumptions that come along with being not only the fairer sex, but the virtuous one. For centuries, female sexual desire has been pathologised and policed, and this history of stigma lingers today, making women’s caution in embracing their sexuality an understandable response to a culture that has long treated it as suspect or excessive.

Even now, despite the abundance of entertainment that embraces female sexuality – from female rap, with artists like Cupcakke effortlessly weaving rhymes about their sexual escapades, to films like Challengers (2023), Nosferatu (2024), and Babygirl (2024), where female leads possess unapologetically complex sexual appetites – our culture still struggles to accept women’s desire as full-bodied: contradictory, nuanced, and ultimately messy.

So, where do we go from here? The goal isn’t to prove that women can be just as "bad" as men but to redefine desire on our terms. While it may feel gratifying to act as the gatekeeper of what constitutes "good" sexual expression, that role is just as confining as the restrictions we seek to escape. As with all oppressive structures, the key lies in rejecting the notion that there is a single "correct" way to be sexual: discomfort will always be part of the conversation around desire. Still, perhaps in making space for that discomfort, we also make room for a more honest, liberated understanding of our wants.