Culture Slut: Showgirls and Pulling Back the Curtain on Showbiz

Ever since I’ve been working night shifts, which is about six years now, I have had a New Year’s Eve tradition of cooking myself a really nice pizza and eating it in the office whilst watching one of the greatest films ever made - Showgirls. Widely panned on its release, Paul Verhoeven’s 1995 erotic epic explores Hollywood’s favourite subject; the inner workings of showbiz, the world behind the curtain, backstage drama and the curation of stardom. Some of the most beloved Hollywood films rest on the inspection of its own mythologies, from the multi-generational interpretations of A Star Is Born to the host of celebrity biopics that are dumped on us with increasing frequency, stardom is cinema’s greatest product. How does one become a star? Who were stars before they were stars? What happens when stars cease to be stars? These are all questions Showgirls sets out to explore, and in doing so it joins a long line of exceptional films doing the exact same thing.

There are two films I see as being the most influential to Showgirls’ storytelling, and as a triptych they encompass the whole of 20th century American cinema, 42nd Street from 1933, and All About Eve from 1951. All three follow the story of a starry-eyed young protagonist infiltrating the world of showbiz, first in the chorus-line or other small role, and eventually being elevated to star of the show, no matter the cost to her or those around her. They show the difficult nature of breaking into a notoriously intense industry, the sacrifices of those involved and the perseverance and cunning of those looking to rise to the top. In all of them, they show the joy of finally becoming the shining star, the goddess of the stage, but equally how there is always a dark shadow waiting in the wings, a nod to the corruption, ruthless scheming and cruelty that permeate this world. Hollywood’s best movies are about Hollywood, and how showbiz works because that’s what they know best. The constant inclusion of the dark underbelly of the performance world isn’t just a literary trope employed to give a story an arc, its very real and always present.

42nd Street is a pre-code musical directed by Lloyd Bacon, but is remembered as being one of the sparkling jewels in the crown of choreographer and musical director Busby Berkeley. Famous for films like Golddiggers of 1933, Dames and Ziegfeld Girl, Berkeley’s huge production numbers and kaleidoscopic dance sequences have stunned audiences from the inception of the Hollywood musical in 1930, straight up to the present day - the most recent reference I can think of being in 2022’s Don’t Worry Darling (remember the dancers in the dream montages).

The story follows Peggy, played by Ruby Keeler, auditioning for the chorus in a new spectacular stage show helmed by famous director Julian Marsh, played by Warner Baxter. After making friends with the right people and some sheer dumb luck, she makes it into the show which quickly gets started on its elaborate production numbers, all to the glory of the beautiful Dorothy Brock, played by the incredible (formerly) silent film star Bebe Daniels. The show itself seems absolutely unhinged and none of the musical numbers that they show them rehearsing seem to have any common thread or theme, but that’s beside the point. Then shock! Horror! Bebe Daniels breaks her leg and cannot go on stage for the opening night of the show. Who will replace her?

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Of course it’s our Peggy, Peggy the ingénue, Peggy the underdog, but can she carry this show on her own? Just before she goes on stage, she receives two important pieces of advice that I have used in my own stage career, and that I have in turn imparted to new performers.

The first is from Bebe Daniels, and she says that The Audience wants to love you, so get out there and let them. The second is from the show director, who gives the now iconic line “You’re going out there a youngster, but you’ve got to come back a star!” Do we think she does? Of course she does! The film ends with some of the most unhinged, lavish production numbers I’ve ever seen, including a scale remake of a New York street, complete with murder, rape, suicide, police shootings and a skyscraper composed entirely of tap dancers with light up signs, which then fades to rapturous applause.

This main theme seems to be the kind of aspirational storyline that made Hollywood so popular with the general public. Good, normal, hard-working girl makes it big and becomes a star! Her dreams come true due to her own talent and personality; all is right with the world. That does happen, but every other part of the film is informing us about the ruthlessness of the star making system.

At the auditions, all the girls line up to show off their legs whilst the director inspects each of them individually, dismissing those who aren’t the right shape. The show is funded by a rich businessman because he wants to take Bebe Daniels to bed, and she is forced to make him believe that she will because otherwise he will shut everything down. Peggy only makes it through the auditions because the girl she is standing next to in line is sleeping with one of the directors, who she makes green-light her and her friends for the chorus. Bebe Daniels has a secret boyfriend who the show producers have beaten up by local gangsters so that he won’t blow the ruse with the wealthy investor. During Peggy’s final rehearsals, she is kissed passionately by the director, under the guise of running lines with her, reminding us that Hollywood has exploited its performers since its inception.

Even at the very end, after the spectacular final number, we see the audience leaving the theatre, wondering hungrily about what will come next. We are shown that the audience is never satiated, never full, always wanting more. Flashes of brilliance are just that; flashes.

Whilst Showgirls may take its setting from 42nd Street, it models its central plot squarely on 1951’s All About Eve. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, it tells the story of Eve Harrington, played by Anne Baxter, a young fan of the inimitable star Margo Channing, played expertly by Bette Davis. Eve becomes Margo’s assistant and studies everything she does, how she walks, how she talks, what she drinks, how she acts on stage, and very soon she manages to finagle her way into an audition to be Margo’s understudy. Of course, Eve is soon revealed to be a scheming little vixen who sabotages Margo so that she might take the lead role in the play and become a star in her own right. But her fame doesn’t give her peace of mind, because in order to succeed she’s had to ally herself with a viperous theatre critic who believes she now belongs to him, and in a genius final scene we see a new young fan bluff her way into Eve’s dressing room and set herself up as the next ingénue fatale.

These are female characters who have lived full and exciting lives, and whether or not they are on the decline now, they have previously ascended and shone more brightly than anyone else.

All About Eve is one of the sharpest and smartest screenplays ever written, casually throwing out lines that are repeated today by everyone from sophisticated critics to drag queens to humble columnists. “Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy night” is uttered by Margo Channing as she downs her second martini, preparing to throw a fit about being passed over for Eve. In an argument with a playwright, Margo tells him that all playwrights should be dead for three hundred years before their work is produced so they can’t meddle with an actress’s performance, when the immediate cutting reply comes - “That would solve none of their problems because actresses never die, the stars never die and never change!” A dig at the ageing leading lady.

Margo and Eve’s relationship starts off as flattery, moving briefly to friendship and then diving into competition and jealousy, particularly around Margo’s boyfriend who Eve attempts to seduce. There is no coincidence here like for Peggy and Bebe Daniels, Eve has engineered Margo’s downfall so that she might shine brighter. As Bette Davis says with perfect contempt, “I detest cheap sentiment.”

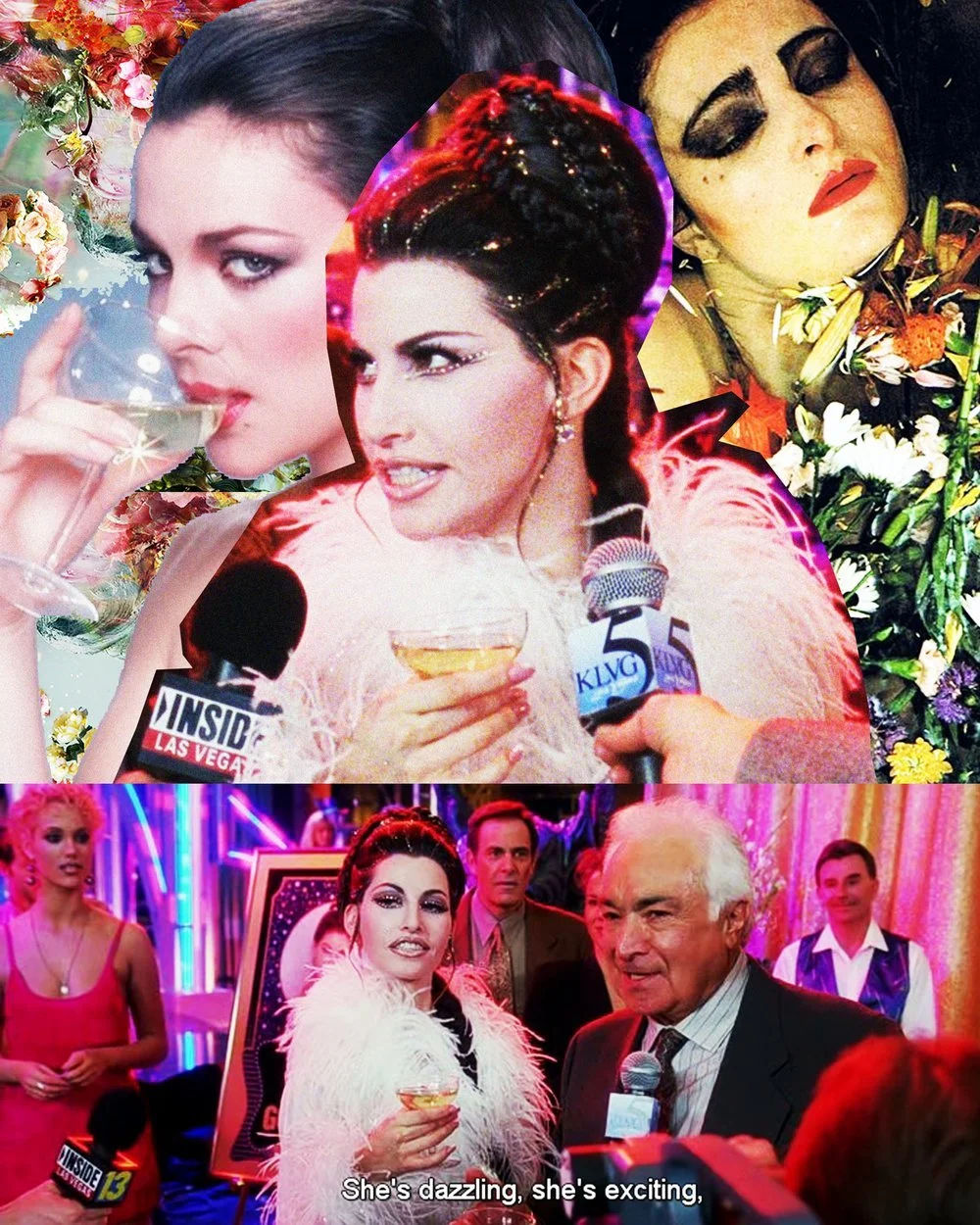

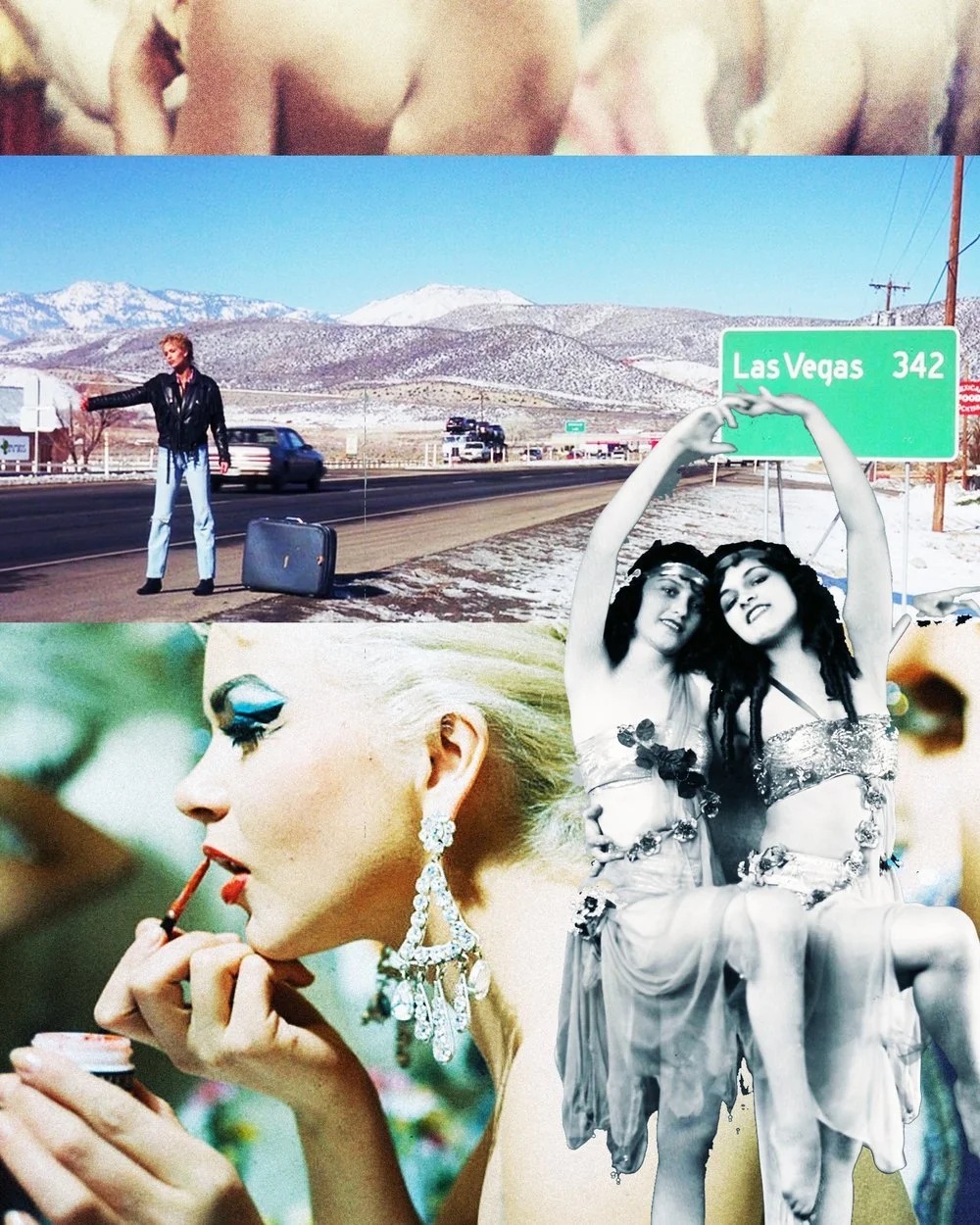

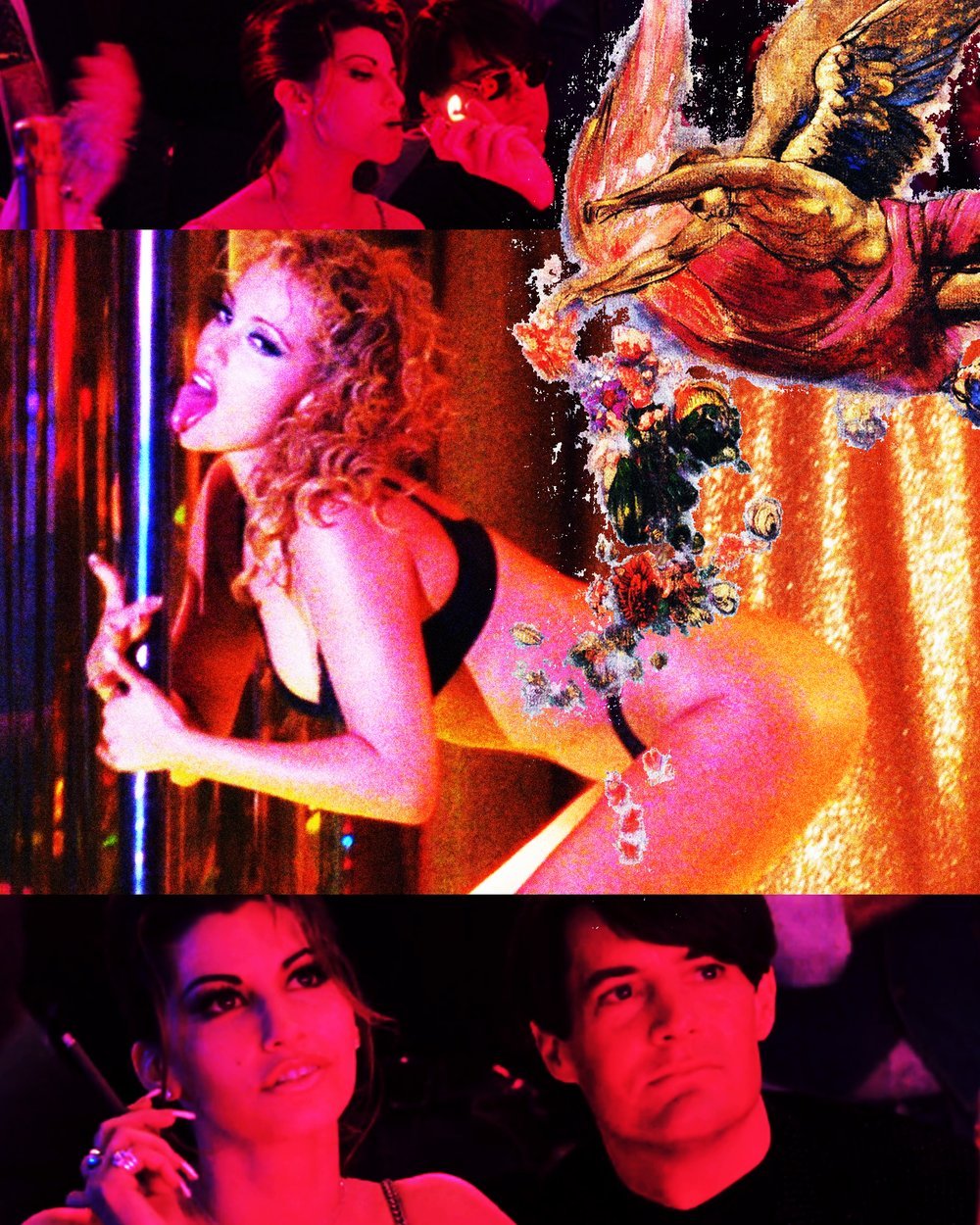

Showgirls unites these two films, taking the best from both and becoming a bizarre camp odyssey in its own right. We follow Nomi, played by Elizabeth Berkeley, as she travels to Las Vegas to become a dancer. She starts off in a sleazy club, but after a chance meeting with the biggest star on the strip Cristal Connors, Gina Gershon at her surreal best, she auditions for the chorus of Goddess, an erotic dance show at the Stardust Hotel. Here, she fights her way through the underworld of backstabbing dancers and predatory producers and becomes Cristal’s understudy. The two women have a flirtatious yet adversarial relationship, which culminates in Nomi pushing Cristal down the stairs and taking her place as star of the show, but it’s not long before we sense another dancer looking to follow in Nomi’s ascending footsteps. After a grim denouement, Nomi leaves Vegas in search of a new place to conquer and heads in the direction of LA, to Hollywood itself.

In Showgirls, Verhoeven tells us that the house always wins. Individual breakthroughs and ascension to stardom is just a small part of a much larger system designed to exploit everyone in it, from the dancers to the crew, to the producers and beyond. The audience always wants more. There is always someone younger and hungrier coming down the stairs behind you. The star is never in control of her own destiny, she’s always at the mercy of the institution that has elevated her. Peggy is fish out of water, willing to do whatever she is told, ready to be taken advantage of. Eve’s scheming places her in the top spot, but she is at the mercy of the critics and directors and playwrights that control her world. Nomi is forced to realise that she is expendable for the sake of the show, everything she cares about can be bought and discarded if it doesn’t benefit the system.

What about the eclipsed stars, the women who were discarded on the way? Bebe Daniels as Dorothy Brock escapes her courtesan relationship with the rich investor and is able to run away with her secret vaudeville boyfriend. Margo Channing marries her long term lover and stops obsessing over her rapidly disappearing youth and beauty. Cristal Connors takes a nice fat insurance settlement and enjoys the first rest she’s had in years.

These women all take a step back from stardom a little worse for wear but, importantly, with knowledge and power. They are such compelling characters to us an audience decades and decades later because they have something that Hollywood still struggles to give its female characters: experience. These are female characters who have lived full and exciting lives, and whether or not they are on the decline now, they have previously ascended and shone more brightly than anyone else. There is nothing more enticing than a fading star, or a star on the brink of explosion. Look at Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, Vivienne Leigh in A Streetcar Named Desire, Judy Garland in A Star Is Born.

Real life is no different, look at the more modern public obsessions with women like Amy Winehouse, Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan. These are all women who have been touched by stardom, transfigured by it, pushed to the brink. Some of them go over the edge, some manage to land safely, but they all went out as youngsters and came back as stars. The stars never change and never die. They all had people gambling on them. They all headlined in Goddess at the Stardust Hotel, and the house always won. Slow curtain, The End.

Words & Collages: Misha MN

Misha has a Showgirls zine available to purchase, message them on Instagram to find out more.