Young, Uninsured and Sciatic

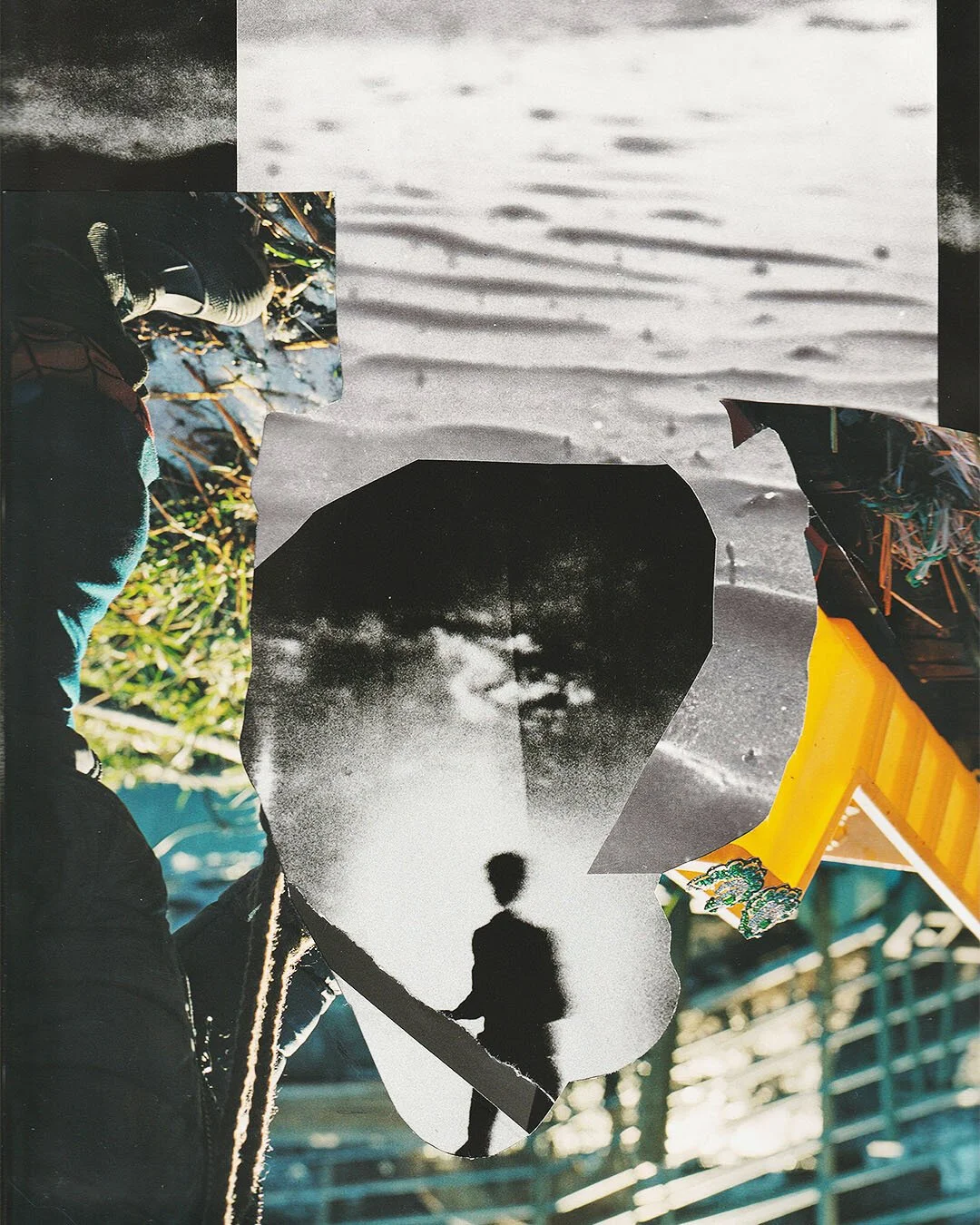

Make it stand out

I sat in front of the Physician’s Assistant, with my legs awkwardly propped up on the footplate of the wheelchair, trying my best to focus on her questions.

“Do you play any sports?” she asked. No, I had said. I also didn’t work out intensely, didn’t have any family history of degenerative musculoskeletal diseases. I hadn’t fallen recently either. I was only twenty-three. Even though none of the risk factors seemed to line up, the pain radiating down the right side of my body was very real, and very much sounded like sciatic nerve pain according to my web searches. The PA reached the same diagnosis and sent me for x-rays. Before I was wheeled out of the room she asked if I had questions. I did.

“What are the chances that this could be caused by stress? Like emotional stress?” I had asked. She told me it wasn’t out of the question, but it also wasn’t something they could test for.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The x-rays came back looking normal, and I was prescribed a muscle relaxer and an anti-inflammatory (essentially a larger dose of over-the-counter Aleve). “This is going to make me walk again?” I asked incredulously. “Yes,” the PA had responded, “But you should stretch when you can.”

Stretching seemed like the destination at the end of the tunnel I would never reach. Two days previous, what had started out as a weird twinge around my right hip had quickly escalated into a shooting sensation down my right leg, which left me unable to move. I spent the first night functionally paralyzed on the floor of my room, at one point looking for something within arm’s reach to vomit into, so I nauseated from the pain.

My housemate brought me ibuprofen and water the next morning after I texted him. The pain died down enough for me to sleep. The following day, though, I was still unable to sit up, so he offered to take me to urgent care. I agreed, and he had to carry me into the building.

And here was the PA, advising me to stretch. I fully expected to receive a prescription of morphine or to be wheeled into emergency surgery, and yet here I was, being sent home with a glorified Aleve pill, a print-off about sciatica, and some stretches to do.

Over the course of the next week, still bedridden, I read everything I could about sciatica: Most people experience this condition when a slipped disc is pressing on the sciatic nerve. Thankfully, most people who pursue conservative treatment methods, such as stretching and walking, recover just as well as those who undergo surgery. Disturbingly though, many people don’t know the exact cause of their sciatic pain. I quickly figured out the muscle relaxers did nothing for me except make feel drugged. The cause of my condition was as amorphous as ever.

Every day, the pain receded a slight bit more. It took me a few minutes less to sit up every morning, and eventually, I could even put both feet on the floor, then flat on the floor. It wasn’t until I was almost walking, that I found the courage to search what I didn’t want to search: the connection between nerve pain and PTSD. The year anniversary of being verbally abused and threatened with sexual violence by an ex-partner was rapidly approaching, and I was afraid that triggering my trauma might also trigger another episode of sciatica, leaving me spending another night on the floor and another week or two away from my job.

I immediately found articles discussing links between PTSD and chronic illness; apparently those suffering from PTSD are more likely to develop chronic conditions including nerve pain, digestive issues, and even heart and lung problems.

As someone without unstable health insurance, I have never sought a diagnosis for PTSD, but I still recognize some of the items on the list of symptoms in my own behavior, from the macro-level beliefs like the whole world is inherently dangerous and no place is entirely safe, to the periods of being hyper-alert and my inability to fall sleep unless the lights are on.

My first instinct had been that my pain was caused by some kind of emotional stress – and there is a theory that stress can cause the body to deprive the nervous system of oxygen, especially the lower back, and cause pain – and even cause sciatica itself.

Besides the link between PTSD and chronic illness, the other horrific fact that I found in my searches was that marginalized and oppressed people are more likely to experience PTSD.

Even though PTSD is typically associated with combat veterans, certain demographics are at higher risk of developing PTSD; namely, women, racial and ethnic minorities, those with less education, and those with a lower socioeconomic status. Further, certain types of trauma are even thought to be more likely to lead to PTSD, including that which continues for a long time, does not allow means of escape, and is man-made.

Systemic oppression – both manufactured and inescapable – is not only pervasive and insidious power imbalances that loom over day-to-day life, but an injustice that leads to tangible and individual acts of violence done to actual people. It’s an absolute recipe for developing PTSD.

It also raises the question for me: Is my belief that the world is inherently dangerous a symptom of disordered thinking, or is it very valid and the rationale very real, as this view is predicated on my ex-partner’s verbal abuse and the broader systems that insulate him from ever facing any consequences, not to mention all the men I have known who fit this prototype? As a woman, to some degree the world is an inherently dangerous place for me, in a way that it’s not for someone like him, as these systems are both unable and choose not to hold him, and those like him, accountable.

Even though I may never know the exact causes of my sciatica, and even though I may not know if I actually meet the criteria to be diagnosed with PTSD, it doesn’t change the fact that it is truly unfair that systemic oppression can affect people at the health level, at the molecular level. And what I find truly frustrating, is that under the headings of “treatments for PTSD,” there’s only listed therapy, medication, maybe acupuncture, as opposed to treating one of the problems at the source, and dismantling systemic racism, white supremacy, the patriarchy, the wealth gap. The political is personal, and it extends as far as physical health.

Words: Stoly Manning | Illustrations: Ella Soni