The Power of Revenge

While many may think that the rape-revenge genre of film is composed exclusively of exploitative films that warrant no critical or feminist analysis, its primary goal at its inception was to offer an indictment of the justice system that overwhelmingly fails to protect rape victims, creating an onscreen vigilante heroine to enact revenge on their fictional abusers.

Born out of second-wave feminism and its fury towards the patriarchy, rape-revenge films seek to remedy the notion that victims of rape must stay silent. However, despite commonly featuring female protagonists, few of these films can actually be considered feminist since many perpetuate victim-blaming, implicitly glorify male violence and favour graphic brutality over any psychological exploration of the consequences of trauma. This is the direct result of male direction and women being denied the ability to tell their own stories from their perspective.

Films made by men can indeed be feminist, but when a man makes a film about a woman being sexually abused, the presence of the male gaze means that her representation is intrinsically sexual, and by implication there is an aspect of the depiction that is made for male pleasure and male consumption, thus diminishing the impact of the abuse itself. Therefore, in order for a rape-revenge film to be considered feminist it must be female-led both on the production level and on screen in order to eliminate the male gaze and allow women control over how their bodies are viewed.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The genre originated with Meir Zarchi’s 1978 film I Spit On Your Grave which at the time was described by prolific film critic Roger Ebert as ‘a vile bag of garbage’, a sentiment that was echoed by the mainstream media. Nonetheless, as Zarchi’s film garnered a cult following, it was adopted by some radical feminists who interpreted it as ‘feminist wish-fulfillment’, whereby the protagonist’s retributive violence against her abusers was seen to symbolise the anger women feel, yet are unable to act upon. (It is important to note that many female artists, including Yoko Ono, Valie Export and Ana Mendieta, were responding to the subject of rape through their art at this time, although few of these works matched the impact of Zarchi’s film, thus showing not only the importance of accessibility and medium but also the power of the patriarchy in suppressing female voices.)

Many female-directed rape-revenge films made since 2000 have been made with the purpose of reworking the genre for the 21st century. While there are many that offer a psychological exploration into the consequences of sexual abuse in tandem with revenge-seeking, one could argue that these deviate too far from the archetypes of the rape-revenge genre, thus creating a different sub-genre entirely. There are fewer examples of sexualisation of a female protagonist by a female director in contemporary rape-revenge films, indicating a desire to deviate from this generally one-dimensional presentation of women, however these films’ similarities to the rape-revenge films of the 1970s offer insight into how feminism has progressed as well as the necessity of female direction.

The overt sexualisation of the protagonist in these films has the intention of satirising the sexist tropes inherent to the genre, thus highlighting the importance of the elimination of the male gaze. The most salient instance of this is Revenge, Coralie Fargeat’s aptly titled rape-revenge film made in 2017. Without a deeper understanding of the history of the genre it might be easy to disregard the film as an unnecessary addition that says nothing new or interesting about its subject.

However, the film’s exaggeration of the heroine’s sex appeal and the foregrounding of the men’s predatory natures mean that Fargeat’s film should be understood as both a satirical reworking of the rape-revenge film and a brutal display of anger at the male gaze. Fargeat’s characters have minimal depth, instead operating as symbols for different attitudes towards rape and gender relations, so that attention is kept solely on their actions and their bodies. The female direction and the satirical exaggeration of the heroine’s sexuality — her name, Jen, is the same as that of the protagonist in I Spit on Your Grave, indicating the intertextuality within the genre — results in a comprehensive dismantling of the male gaze. This shows that even when a rape-revenge film follows the usual template of the genre, female direction, and its elimination of the male gaze, is a vital component in subverting the genre, as well as being an essential ingredient if it is to achieve its feminist potential.

In a move that differs from other films of the genre, in Revenge the rape itself is not graphically shown, yet the build-up to it is almost as disturbing as the assault itself. By not depicting it, precedence is given to its anticipation and also the anger of the male characters, which demonises them even before the rape happens and thus encourages viewers to feel the same unease as Jen, while showing that there does not need to be any physical damage to a woman’s body in order for it to be violated.

By not showing the rape, Fargeat eliminates the sexual aspect of it, illustrating it for what it is here: an act of violence predicated on a man’s desire to completely possess a woman’s body. The preceding scene, between Jen and Stan, her rapist, is almost devoid of dialogue, being filled instead with extended gazes and awkward silences which accentuate Stan’s predatory nature. Immediately prior to the rape, he repeatedly asks Jen, ‘What is it you don’t like about me? […] Why am I not your type?’ since he is confused by her lack of reciprocated interest in him after they danced together the previous evening, making it clear that he does not, or refuses to, understand that flirting does not equate to sexual interest and consent, while also revealing his feelings of entitlement to her body. The fragility of the male ego is a pervasive theme throughout the film and is displayed, for example, by the increasingly frenzied violence the men use in their attacks on Jen in response to her own violent behaviour, which in superseding theirs undermines their masculinity by turning them into the victims.

The exaggeration of Jen’s femininity and sexuality invites comparison with Zarchi’s film, despite I Spit on Your Grave favouring the male gaze in its suggestive depiction of Jennifer rather than satirising her hyper-sexualisation. However, in Revenge, Jen’s beauty serves to exaggerate the lasciviousness of the men around her, and although her femininity initially suggests vulnerability, Fargeat subverts this impression by making it an instrument of her brutality. It is doubtless down to Revenge being directed by a woman that has led to it being read as feminist body horror, reminding its viewers of the dangers entailed in objectifying and feeling entitled to a woman’s body.

The emphasis on all the characters’ bodies, as well as there being more male than female nudity in the film, indicates that it seeks to redress the balance which has historically been lost in the instrumentalisation of women’s bodies on screen. Instead of Jen’s depiction as simply a sex symbol being her character’s governing principle in the film, both her physical form and her character become embodiments of pure anger.

Jen’s implementation of revenge is in keeping with the graphic violence characteristic of the rape-revenge genre. Despite the visceral nature of the violence depicted, Fargeat’s film does not revel in its savagery, and when Jen kills one of Stan’s acolytes she is shocked by her brutality. Nor does she engage with her tormentors in the way Jennifer does since in Revenge they are also out to kill her, and the fear Jen felt for Stan before he raped her stays with her.

Since fear is generally seen as being a weak, and therefore feminine emotion, the men’s fear thus emasculates them, while in the final scene, when Jen kills her boyfriend Richard, there is a strong sense of anti-climax because of the extended sequence with the two of them literally chasing each other round in circles, the opposite of a final dramatic face-off. Richard’s nakedness in this scene makes obvious his vulnerability, but also his failed attempt at asserting his manhood as sole proof of his superiority, inviting us to conclude that being male is in itself ultimately inconsequential when it comes to strength. This is the film’s final satirical gesture, generated out of an absence of sensationalist brutality, a sustained illustration of desperation and a visual representation of the cyclical nature of violence.

Such gender-based analysis of films is innately binary, yet the difference between the male gaze and the female gaze and their respective implications must be acknowledged and dismantled as the idea of binary gender becomes obsolete. Until then, the example already set by female directors should be taken up by other artists of marginalised identities, paving the way for equality to seep into the cultural consciousness through film. Revenge and similar post-2000 films, such as Baise-Moi and A Vigilante, ensure that the female body, as well as gender non-conforming bodies, become the norm, instead of being viewed as ‘the male other’, predicated on a lack or a difference, thus being subjected to humiliation, violence and hatred motivated by a fear of the unknown. Yet unless they are directed by women, rape-revenge films will continue to oversexualise their protagonists and deny them full autonomy at the expense of allowing them to embrace their full potential. Thus, instead of adhering to the ideal of the archetypal male hero, these films allow their female protagonists to be their own, and their audience’s, long-overdue hero.

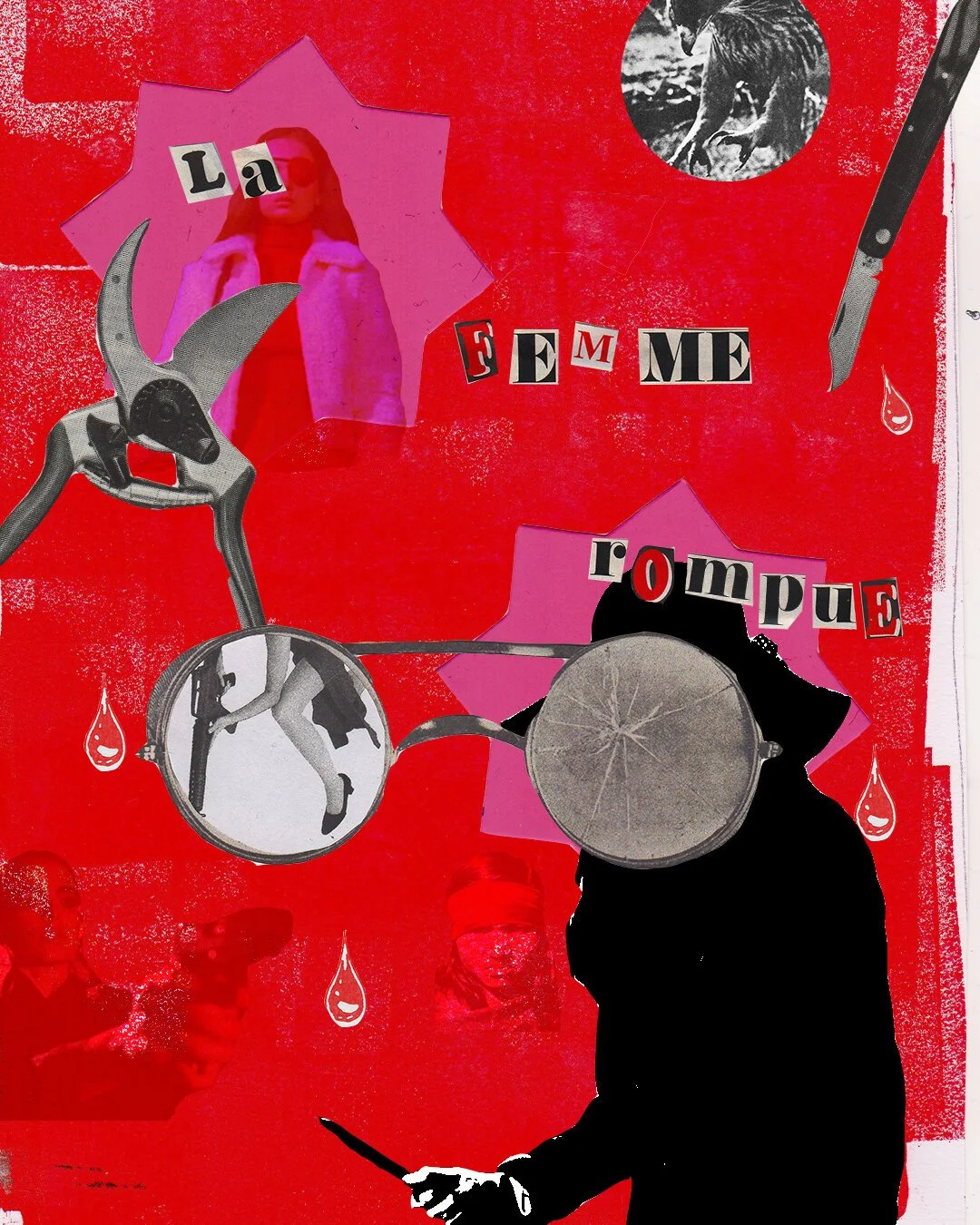

Words: Arla Albertine | Artwork: Rosa Burgess