The Poetic Prophecies Of Greer Lankton

Make it stand out

Trigger warnings: anorexia and eating disorders, gender dysphoria, drug abuse, overdose, suicide.

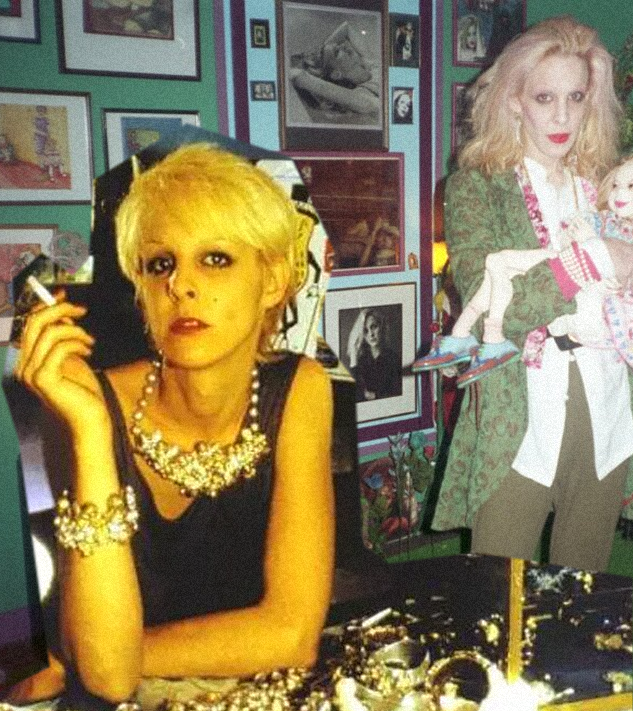

There are a couple of magical things about this sketchbook by Greer Lankton from September 1977. The first, that it exists and has survived. The second, that it has been published and is now widely available in this physical facsimile form. Greer Lankton is a trans icon, a trailblazing artist from the downtown Manhattan scene of the 1980s. She was best known for making doll sculptures: sometimes creepy, often wonderfully strange, usually very funny, occasionally terrifying. She made dolls of Divine, Andy Warhol, Candy Darling — and a cast of her own characters, including Princess Pamela, Cookie Puss, Missy, Sissy, and Grandma Tillie. Much of her work was displayed in the window of Einstein’s — a boutique fashion store run by her husband, Paul Monroe — but she also had exhibitions at the Civilian Warfare gallery. In 1995, her sculptures were included in both the Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale.

After she died, in 1996, her family donated her dolls, sketchbooks, and large collection of photographs to the Mattress Factory in Pittsburg; much of it is now digitised and freely available to peruse online. This particular sketchbook, September 1977, was gifted to Joyce Randall Senechal, who later donated it to MoMA. Primary Information, an independent publisher based in Brooklyn, has published a careful and intricate copy of the manuscript: her notes and thoughts, diary entries, her ink sketches replete with colour and highlights.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

September 9th 1977: she begins with a food diary — she struggled on and off with anorexia and eating disorders throughout her life. This feels, despite its quotidian nature, like an intrusion. She has allergies and tries to understand them better. One page bears the heading, “Emotional aspects of asthma” — a sentence that feels it could have been the lead tweet in a viral Twitter thread last week.

She begins in a methodological mood, day by day, then suddenly confessional; it switches from diary to journal to sketchbook. She makes graphs, charts and diagrams about gender and identity and feelings. You can see her thought processes: she is working through, working herself out. It feels as if she might have made the decision to medically transition while writing in these very pages. She decided to start hormones and undergo gender-affirming surgery in 1979.

Greer feels like a prophet; her words, highly poetic and often magical. Her thoughts feel ahead of their time — or, perhaps, we just don’t have an expansive enough sense of trans history. “Even without hormones I have changed,” Greer writes. “As David + Lee’s friend said last year ‘you’d be the perfect transsexual’”. She is direct yet nuanced. “As a woman some men will discriminate. As a sex-change many people will discriminate but alas does it really matter[?]” While this was written privately, it also feels perfectly suited to public publication. “Naturally I’ll be Miss Drama. It’ll be scary, painful. Long… and disappointing at times. It couldn’t be worse than it was. People will stare but they always have. It’s worth it. I will still be doing what I’m doing only happily + constructively”.

She quips, “I probably shouldn’t figure model during the transition”. Many of her dolls would be trans — or genderfluid or agender. She explored gender and its relation to the body throughout her work. She continued to keep sketchbooks and journals throughout her life — including an astrological birth chart and an address book labelled THE DOLL CLUB. How camp. I’m sure today's dolls will find something relatable in either her writing or her art. As Alaska Riley (@onlinegirlie) wrote, inspired by Greer’s sketchbook, “I’ve said often that transness is a testament to intuition. Led by a profound understanding that our bodies are malleable in nature, we claim agency by assuming the task of evolution.”

“Greer feels like a prophet; her words, highly poetic and often magical. Her thoughts feel ahead of their time — or, perhaps, we just don’t have an expansive enough sense of trans history.”

“After Greer had the surgery, Mr. and Mrs. Lankton used to call me their third daughter,” notes Senechal in her afterword to the diaries. “I was impressed with how loving and supportive they were with all of their children. It was a calm household, with a lot of good food and laughter. I always felt welcomed, included, and loved.” It’s great to know that, despite her litany of worries, she was accepted and loved by her family.

Greer scrawls on one page, “As the late great Candy said, ‘I’ve got a right to live’,” next to a simple pen portrait of the Warhol superstar. The texture on the page adds a sensitivity, a personality. Greer feels close. There are many pages I want to cut out and frame on my wall, powerful artworks by an artist-in-waiting.

Primary Information specialise in publications like this, fine art ephemera with an emphasis on the Downtown Manhattan scene and queer art: David Wojnarowicz’s exhibition catalogue, In the Shadow of Forward Motion, for example, or a compilation of the independent queer magazine, Newspaper (1969–1971). This year, they’re releasing two facsimile copies of poetry collections by queer Asian-American painter, Martin Wong, and two books by provocative queer photographer, Jimmy DeSana. These are brilliant books, vital documents.

And there’s something important here, especially as concerns queer and trans history — how it’s written and who gets to write it. Archives are full of obscure ephemera and personal documents, but many are only accessible to researchers and specialists. Queer life often plays out purely in private: our relationships to love, desire, sex, gender. How these often play out behind closed doors for us; sometimes, only in our thoughts, our private diaries, in imagination. There’s an ongoing trend in institutions organising archival exhibitions and publications, like this one, reproducing otherwise obscure documents. It gives a window into another time, another place. Queerness can often feel isolating — documents like this remind us that we are never alone, we are everywhere, we have always been here, hiding in plain sight.

“After Greer's death, the Lankton family gifted me twenty-one years' worth of Greer's journals, including this sketchbook,” writes Senechal. “I decided to transcribe them into a digital file, which took a couple of years. Often it was emotionally difficult to get through them. I would cry when I read about how much pain she was in.” Afterwards, she donated the sketchbooks and journals to the Department of Film at MoMA.

Greer’s work persists — as does her energy. Senechal concludes, and I can’t think of a better ending, “Greer had a beautiful spirit and I miss her every day. But as she writes in these pages, ‘I will not die, I will become.’” After all, aren’t we all in a state of constant becoming?

Words: Louis Shankar