The Pleasures of Online Research and the Labour of “Googling”

Words: Madison Jamar

Make it stand out

Monitors lit the room with the dim glow of their screens which all projected the same image: pink and purple hues stretching in rays over a star speckled midnight-blue sky. The aluminium finish of the then latest Mac desktops lining the desks of the library’s computer lab highlighted the newness of my high school, which opened its doors in 2008, my freshman year. Though the majority of classroom computers were the bulky black Windows PCs we were familiar with, the acquisition of the Apple Macs along with other new tools such as SMART boards and projectors signalled an embrace of the coupling of tech advancements with education - as well as a higher property tax in comparison to neighbouring school districts. These classroom additions promised an ease in teaching, implying in turn an ease in learning.

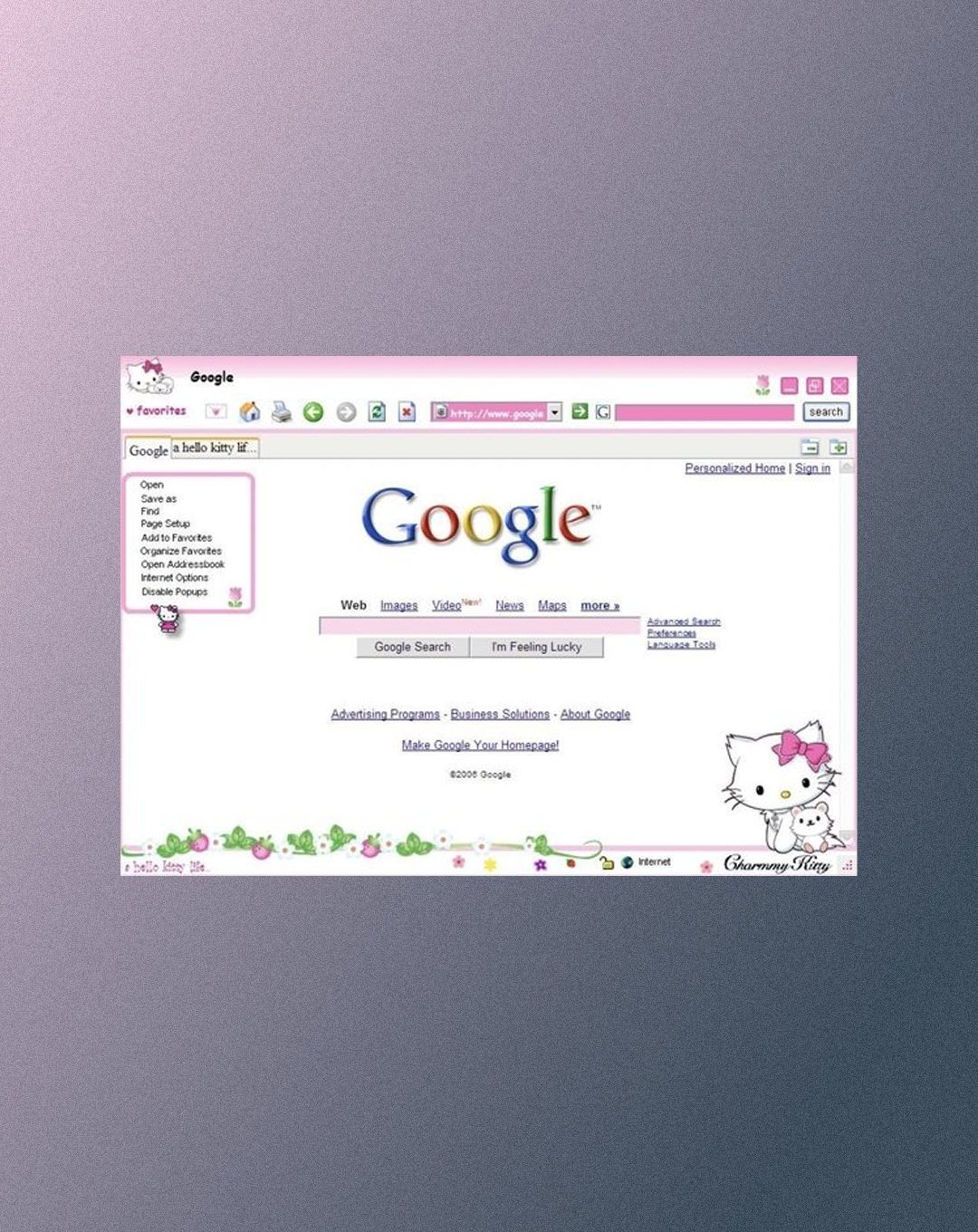

We gathered yearly in the Apple-fied library lab for our annual refresher on the best research practices. These primers had occurred since elementary school, when we were taught the differences between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources. In middle school the lessons had evolved as we were introduced to databases like JSTOR, which allowed us to scour hundreds of academic journals. The advent of public internet search engines like Yahoo! Search, Ask Jeeves, and the soon to be ubiquitous, Google, introduced boundless streams of digital material that simultaneously rendered knowledge more accessible and muddied the terrain with misinformation.

My teacher stood near the projector explaining that sites ending in bibliographies (.edu and sometimes .org but almost never .com) were our best bet for reliable findings. Wikipedia, he stressed, couldn’t be referenced under any circumstances. It was important, my teacher emphasised, that when uncertain about information found online to cross check it with reputable sources. I wondered during his tirade if this tutorial was worthwhile. Not only had correct citation practices been taught to us multiple times, but it seemed increasingly intuitive as internet use became more central to our lives.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Nevertheless, I took these teachings back to the broadband internet of our home computer. Like its academic database predecessors, Google Search functioned best with the entry of “keywords” that encouraged specificity. Back then, using prepositions, conjunctions, and articulations like “the” could ruin or at the very least, made a Google quest substantially less effective. Searching with full sentences (why was Pluto demoted to being a dwarf planet?) rather than short phrases (Pluto dwarf planet) could also hinder finding info quickly. Music - one of my most searched subjects - could be the trickiest to garner info on that couldn’t be categorised as celebrity gossip. If a DJ didn’t name a song title or artist, I would try to remember lyrics to look up later. An issue that increased as I listened to the local alternative station more often where the featured music was often older songs or lesser-known artists.

“train mars stars.”

“train mars counting stars.”

“she missed train mars counting stars.”

“out back counting stars.”

“holding daisys waits me.”

Did you mean “holding daisies waits me?”

“holding daisies waits me.”

I combed through the Google search pages and YouTube, which had not yet been acquired by the former, looking for a grungy rock song that my mom had forced me to turn down as it rattled the car speakers. Hunting across lyric websites, I finally found Stars by nineties band Hum. Though the process could be maddening, there was also a deep satisfaction in uncovering the answer to the question — something like a deep sigh of relief combined with a euphoric climax — as well as the linguistic mathematics involved in coaxing out appropriate listings from the search bar.

“I didn’t see Google as the ultimate destination for answers, but as a useful step in a larger process of discovery and thought.”

Pleasure in online searches has eroded as Google and other tech giants dominating the web increasingly extract data from users in exchange for a relatively (and tentatively) free internet experience. This comes by way of that old promise of ease, recently exemplified by Google’s beleaguered incorporation of AI Overview into its search engine that offers short summaries to inquiries. In an article for Intelligencer, John Herman notes that the apparent goal of this is to automate the search function, which is a fundamental misunderstanding of what has made Google an essential resource. While a quick answer may at times be useful, these short explainers flatten the experience of researching online. It is an extension of collapsing all vastly different arenas of creation and thought under the worthless categorisation of content.

In its own description of AI Overview, Google states that it “can take the work out of searching.” This admission highlights a key part of its business that the company is usually eager for us to overlook: the labour involved in searching. Its business model is predicated on tracking how users figure out how to best use it and then repackage it back. A phenomenon seen also in social media sites like Meta which introduced Facebook Marketplace and Instagram selling functions after realising users were using the platforms for commerce already.

One of the most pervasive sayings of the 2010s became “Google it”, often prefaced with the word just. “Where can I find more information on this?” someone might inquire underneath a Tweet or post. The answer: “Just Google it”. But like all work, there are skills necessary to execute when Googling It.

As already mentioned in The Polyester Podcast, there is an assumption that people, especially those considered Gen Z and younger, are digital natives. In this view, internet sleuthing is seen as an inherent ability rather than a learned technique among a variety of skills. With the limits faced by public schools, as well as there being fewer places for people to engage in deep dialogue with one another, there has been a shift towards a devaluation of critical thought. In its place we see a synthesising of information in favour of supposed right answers or views. For a myriad of reasons, people are afraid to be wrong and services like AI Overview claims to be a work around this fear, preying on the common insecurity of appearing uneducated. This is particularly insidious after it has been reported that the tech conglomerate has been contracted by the Israeli government to provide AI and other technologies which being used in its continued occupation of Palestine and genocide of Palestinian people.

I can’t help but notice the similarities between the assertions of AI’s take over with that of crypto currency and web3 a few years ago. I hope eventually the bubble will burst. But perhaps the hope of businesses to further outsource labour is too great for money not to be continuously funnelled into further artificial intelligence ventures. Another common saying to denote the ubiquitous search engine’s simplicity and accessibility has been “Google is free,” but these days I’m not so sure the refrain is apt.