The Pink Bed: Framing Femininity through Household Objects

Make it stand out

25 years ago, Tracey Emin made her bed. Or rather, didn’t. And then she put it in a gallery. Outside of her bedroom, her bed, stained with bodily fluids and littered with the debris of a depressive episode following a break-up, is an aggressive display of vulnerability. Emin, a multimedia artist originally part of the Young British Artists group, is recognised for her confessional works that deal with taboo subjects. A quarter of a century after Emin showed My Bed, Portia Munson’s the Pink Bedroom was displayed at the Museum of Sex in New York through til July.

Considered together, the two works prompt a reflection on the ways in which our perceptions of womanhood have changed - or haven’t - over the past few decades. Post-pandemic, in the midst of an intimacy crisis attenuated by hookup culture and dating apps, the vulnerability of Emin’s piece and the impersonality of Munson’s are striking. In an age where notions of femininity are acutely fraught, the pieces give new meaning to objectification and the importance we ascribe to the objects around us.

Portia Munson is an American visual artist whose work often addresses environmental matters through a feminist lens. Munson’s the Pink Bedroom is a sprawling curation of the shiny consumerism that is so prevalent and pervasive it has come to symbolise femininity. The very fact that objects are such powerful symbols of womanhood allows Emin and Munson to make art from what already exists. An ironic meta-commentary emerges: they haven’t made anything new, they are just drawing attention to what society already makes plainly obvious. In different and complex ways, women are denoted and defined by the objects that surround them.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

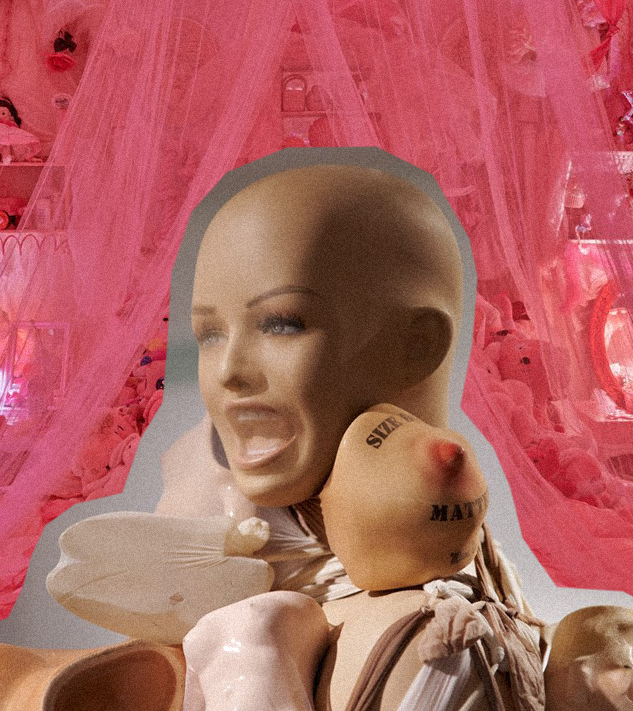

In the Pink Bedroom, the viewer enters a space which is swamped with artificial representations of femininity in various forms: shoes carpet the floor, soft toys make a pyramid on a bed canopied with pink gauze. Yoga balls, bras, vibrators, hangers, fake nails, barbies, teapots, fans and strings of pearls are just some of the objects that tangle, hang and spread across every square inch of the installation. These objects have two things in common: they’re all associated with women. And they’re all monotonously pink. Munson’s commentary on femininity’s historic relationship with the colour isn’t new, but belabouring this point is part of the overall effect of the work. The debris that Emin included as part of her work is the visceral backdrop to the curated femininity of the Pink Bedroom. Empty bottles of Absolut, cigarette packaging, used and unused contraceptives, slippers, hosiery, Polaroid self-portraits and an extinguished candle are littered around the edges of Emin’s wooden bed-frame.

By gathering together the various objects that denote traditional femininity, Munson helps us see how ridiculous they are. Detached from their previous owners and amongst hundreds of others, they lose individual significance. The distinction between what the objects are and what they appear to be is blurred. A hanging drying rack hangs in one part of the Pink Bedroom, paraphernalia of childhood dangling from its plastic frame. It resembles both a baby mobile and a parody of a chandelier, rendered in pink plastic. Munson’s experimentation with representation echoes Ferdinand de Saussure’s theory of language. According to Saussure, the connection between a word and what it denotes is arbitrary and based solely on our experience of that object.

“By gathering together the various objects that denote traditional femininity, Munson helps us see how ridiculous they are. Detached from their previous owners and amongst hundreds of others, they lose individual significance.”

Unlike in the Pink Bedroom, the objects used by Emin are a true reflection of what her bed looked like after her depressive episode. Now they are part of an artwork, they unwittingly take on symbolic meaning. The ends of cigarettes and the dregs of spirits tell a story of exhaustion, pain, love and loss in more ways than one. Following the legacy of Marcel Duchamp, Emin questions the aesthetic and moral values of what we call art and makes a mockery of the symbolism and significance we ascribe to works of art. Seeing the Pink Bedroom in this same light, Munson makes a disturbing point about the objects we ascribe significance and importance to in our lives.

These are objects marketed towards women as a necessity: removed from their owner, they have no individual significance and become a disturbing reminder of this particular experience of capitalism women share. The deeply personal nature of My Bed reminds us of the paradoxical impersonality of the Pink Bedroom. While the former work occurred organically, the latter was created by design, much like these objects that were designed to be bought by women.

The presence of the women who have owned these objects or occupied these spaces is felt more keenly by their absence. Women share experiences such as wearing shoes, drinking alcohol and painting their nails and these are represented in the objects we see in both works. Emin and Munson remind us there is community in womanhood, but there is also loneliness: Emin’s work was the result of a period of intense isolation.

In moments such as these, we find meaning and comfort in things if we lack it in people. An empty bed is lonely, but there is a sense of life having happened there: the sheets are tangled and stained and cigarettes are stubbed out in an ashtray next to it. Whilst the objects used by Munson were once owned and used by real women, they feel alien and lifeless. Instead, the sheer monstrosity and business of the work breathes anthropomorphic life into objects that are, in all their pink plastic glory, inanimate. This same impersonality characterises much of modern life: our lives play out in an online universe: we shop, communicate and date through virtual platforms. We curate polished versions of our lives when the reality may be closer to that which Emin is representing.

The haunting loneliness of Tracey Emin’s My Bed and Portia Munson’s the Pink Bedroom leaves their respective viewers with a surprising sense of hope. It is the women that inspire meaning into these objects, not the other way around. And, ultimately, the absence of the women in the things and spaces they leave behind means that it is possible to escape the traps and trappings of a patriarchal society. However, the irony of Munson’s portrayal of an ultra-feminised capitalist hellscape being sponsored by Satisfyer, a sex toy company and $45 10ml bottles of the scent used as part of the installation which “evokes plastic doll heads, sweet makeup powder, strawberry candy and an overall unnerving aura” being sold online doesn’t go unnoticed. We’ve made our bed. Now we have to lie in it.

Words: Francesca Tiana