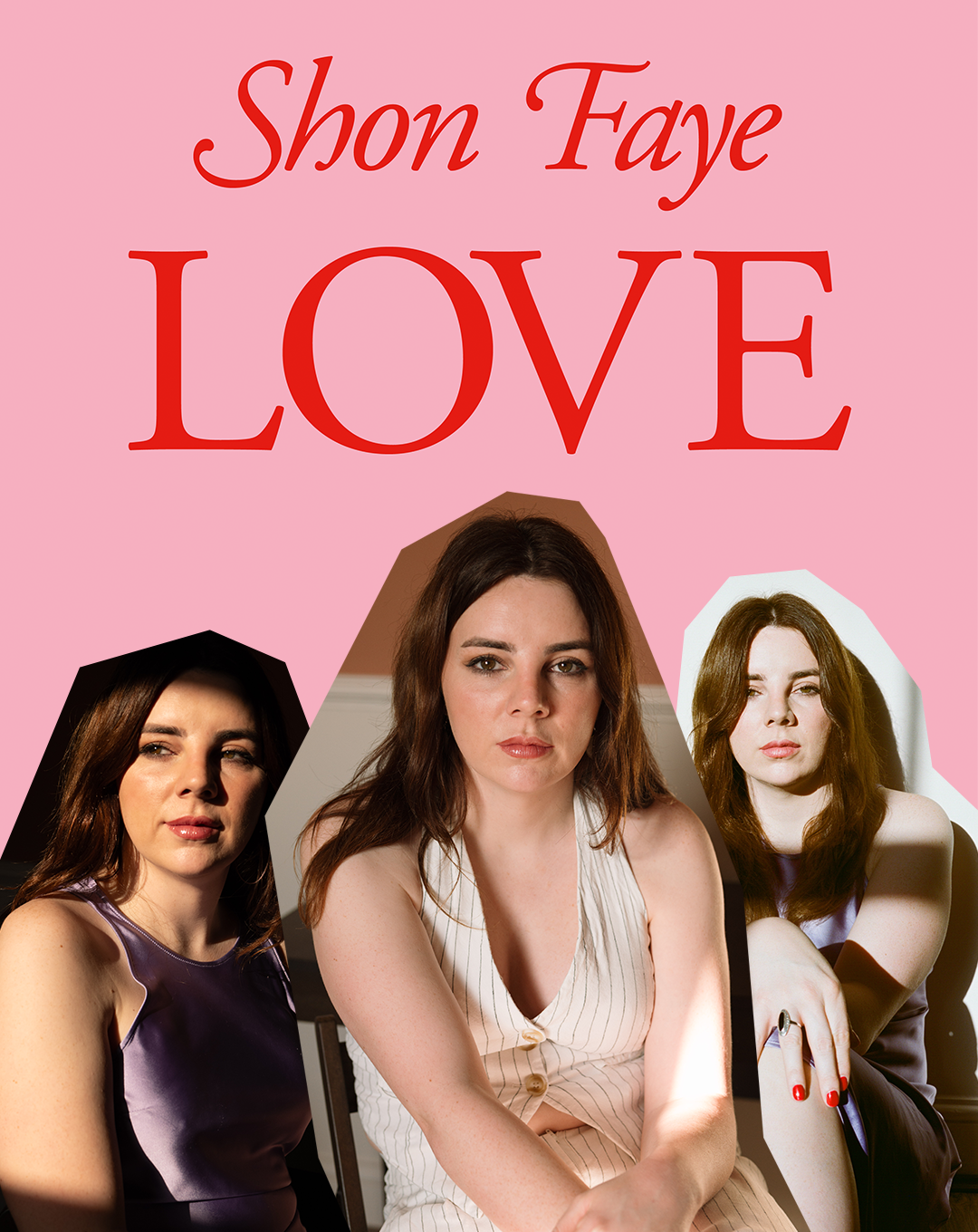

Shon Faye on the Politics of Love, Competitive Dating Rituals and Finding Yourself Lovable

Words: Arijana Zeric | Photography: Sophie Davidson

Make it stand out

Shon Faye grew up obsessed that love was not for her. The author of the acclaimed bestseller The Transgender Issue argues that love should be rooted in society, a responsibility we should share as a collective, rather than just practiced individually in closed partnerships. Sometimes these romantic relations are motivated by something other than love.

In her new book, Love In Exile, Shon analyses her previous relationships, addictions and romantic encounters which leads to her confronting her own sense of unworthiness. She makes sharp observations regarding the various models of relationships, which have evolved over the decades. In contrast, we are forced to look at our reality today. Whilst there are some positive developments for women in particular, we are also dealing with a large sense of lovelessness that spans across society.

She concludes that this sense of exclusion is symptomatic of a much larger problem in our culture, mainly the dominance of consumer capitalism and the possible number one source of our inadequacy; social media. Originally from Bristol, Shon had a short stint in London as a lawyer, after which she quit, moved back to Bristol and came out as Transgender. Here we chat to Shon about friendships, capitalism and how love can be a spiritual experience.

AZ: In the first chapter, you say you needed to let your boyfriend go in order for you to practice your love for him. Did you see yourself as a martyr?

SF: In retrospect I can look back and see that it was for the best and we fundamentally weren't compatible. I was labouring under an immature idea of a teenager who doesn’t think of their love life in grand ways and as you retain more and more maturity, you realise that love is built on much more mundane foundations in some ways. That person and I did not have those foundations, so I don't necessarily see myself as a martyr anymore, but I think that's how it felt at the time.

You write that a search for love should be more political and collective rather than personal, is this a plea for more empathy in society?

I think it's more tangible than that. We live in a culture in which increasingly denigration, lack of respect for people's humanity and their dignity, is celebrated. It's a hegemonic masculine culture of domination, in which you ridicule and dominate the weaker, whoever the weaker is. I actually would say that we have a culture that celebrates hatred and abuse of power. Trans women are routinely mocked and belittled and told how repulsive and unlovable they are. I was trying to seek an antidote to that in my personal life. I would argue that it's the wrong basis to seek romantic love, I think we should be turning our attention to the way in which these grander narratives of hatred and domination need to be replaced by compassion and empathy.

“Mutual pleasure and enjoyment doesn't provide anything to capitalism.”

Do you think perhaps that people's attitude towards caring and loving one another has diminished more as people have been hit by an economic crisis?

In some ways our working lives have become more precarious. The state doesn't care for us. That’s actually putting moral pressure on private family units and particularly couples in order to be the only support for each other, and that is not what was historically the model. But I also think the point about consumer capitalism is that we're constantly fed through devices that we carry with us everywhere now. We’ve been marketed to all the time. The messages that we receive make it harder for us to practice true love. It is “buy this, train like this, eat this, and you will become more lovable”.

What most people are actually practicing is arguably a form of addiction which we mistake for love. It is this addiction to our fantasy. If we buy this, we accumulate this, if we display our value this way then we will feel kind of nourished at the emotional level, and that's not true. The reality is actually that free time for care, support, intimacy is being taken away. Simultaneously, we’re all being turned into products. Look at who is wielding power. It's these tech giants, or many social media companies. Social media has turned actually very nefarious, and what it gets sold is this simulacrum of human connection. What it's actually doing, it's mining us for our data and changing our behaviours into more addictive patterns on the basis that if we spend more time and put more of ourselves into these things, we will feel more lovable and we don't.

You speak a lot about friendships, why do you think friendships are deteriorating and considered less important when they can be such a vital part of people's lives?

It’s because historically, we've just treated friendships as a pastime, until you get into the real process of marriage, particularly for women. Because men were always considered to have these functional friendships connected to work or outside of the home. Whereas women were socialised - and I’m talking of 100 years or 50 years ago - to compete with each other for the attention of men when they're young and I think that has changed. The emphasis for women on the importance of friendship has really grown, but we still have this sense that friendship is a second best relationship. It’s primacy is in your 20s and then that should fall away and you should get settled down to the real business. The reason for that is because of capitalism.

Mutual pleasure and enjoyment doesn't provide anything to capitalism. It's not the same as a heterosexual relationship where you’re taking care of each other whilst also raising children into future workers. It's not the same as your relationship to your colleagues or your boss. And so it's devalued for a very uneconomic reason. However, I think that has changed for women.

Your tone is quite stern during the first half of the book and then it softens more towards the end. It seems you have discovered self love as true bliss or do you describe perhaps something more religious?

I think you're right about the progression of the tone in the book. The book starts in a very vulnerable tone which mirrors my feeling of writing it. In the beginning I refer a lot to external authorities and I cite a lot of other thinkers. I'm trying to grapple with these ideas and as I progress through writing the book, I became all certain of my own thoughts and feelings on this topic and as a result, it becomes softer and perhaps a little bit more focused on my opinions without appealing to outside authority. I share some of the ways in which I came to get to a place of self-acceptance and I sort of grapple with the fact that I have this Ick response to the idea of self love. I think many people do, and I find it quite schmaltzy, and a little bit cliché. But fundamentally, it remains true that I would have struggled with seeing myself as lovable and expecting that to come from a romantic partner so I did actually need to heal the relationship with myself and I try and share a little bit about that.

I also talk about spirituality, and I wasn't always intending to put that in the book. But the reason I did was because I've read so many books about love and bell hooks, for example, writes about her spiritual beliefs. In ancient times the Greeks had multiple words for love and one of them was agape, which is this idea of the unconditional love that the creator has for the created. Now, I'm not Christian, but I still find quite a lot of solace in the idea that there could be a source of spiritual love. I think this has somewhat been erased. We have just descended into consumer capitalism.

Love in Exile by Shon Faye is available for pre-order here.