Sasha Gordon is Balancing Beauty with Discomfort

When you look at Sasha Gordon’s work, you feel her painted selves return your gaze with their reflective eyes, stark like onyx set against a round face, full of unsettled emotion. In her self-portraits, worry is captured in the furrow of an eyebrow, anger in the wrinkles of a nose. When we meet at Stephen Friedman Gallery to talk about her first European solo show, The Flesh Disappears, but Continues to Ache, however, Gordon is quick to laugh. We start the interview gushing about Lena Dunham’s Girls (which she’s seen multiple times), Jeremy O. Harris and the hectic months before this exhibition. “It’s been crunch time,” she laughs. “I’ve been sleeping at my studio, chain-smoking and painting through the night.”

In Gordon’s images, various versions of the artist herself move between rage, sorrow and impishness. Opting for oil paints, she is able to build up the layers into a saturated urgency, asserting the both unease that comes with being witnessed, as well as the embodied experience of existing in a bigger queer, Asian body.

“Sometimes, I found myself uncomfortable in my skin, and dissociating from my body. But asserting its existence connects myself back to this sense of a present self.” Her work captures the details meticulously: the folds and creases of the body, the bend of her fingers, and curls of pubic hair. In a painting of herself accompanied by a doppelganger fashioned from a topiary bush, you sense her double need to hide behind the leaves but also to stand firmly in her exposed body, little wisps of hair delicately framing her face. “So many emotions can be observed through the nude body and its gestures,” Gordon explains.

Talking to her, I find that she expresses her complex ideas in simple, evocative terms. She constantly asks what I think and feel too – it’s a curiosity and kindness that recognises shared vulnerabilities. I ask if it is difficult to bare yourself in your work. “When I am making work for a show, I don’t think how vulnerable it is to show my work until the moment I’m showing it,” Gordon says. “At the show, I’m like ‘Okay, I’m naked, this is a lot.’ But the reason for me to show my work and talk about it is more important than my fears of being vulnerable.”

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

“The transformation of my figures into these non-human forms is partly about escaping. It’s about experiencing things that have been hard to deal with as humans, so you choose to escape your body”

Gordon started painting herself in her first year at Rhode Island School of Design when she was confronting questions about her identity as a biracial woman, born to a Polish-Jewish-American father and a Korean mother. She grew up in a predominantly white town in Somers, Westchester County, New York. “It was weird,” she explains. “I look very Korean but have a really white name. There was a point where I was denying my Asian side, because I really didn’t want to be. I was fluctuating between that and being very aware of my body and how I was perceived in that space.” In secondary school, Gordon largely drew portraits of her classmates who were mostly white, following the art history manuals that favoured thin, Eurocentric women.

“My first painting of myself was this depiction of a Korean bath house, with pink and yellow figures,” Gordon remembers. “One of the yellow figures on the left was in my likeness and it was the beginning of my exploration of self-portraiture.” We discuss the similar sense of silent conflict we felt towards our race, but also how expressing yourself doesn’t always lead to catharsis: “I loved RISD, but it was difficult when I was presenting this really self-exposing art in front of a predominantly white class, where the whole room was silent because they were scared of saying the wrong thing to me, which I get,” Gordon says. “But it’s just like, I want feedback to work with like everyone else.” Yet, as her audience changed, Gordon has felt a shift in her solitude, speaking with women who’ve spoken back with a mutual recognition.

“Painting can be quite selfish. I started out being like, ‘This is just for me.’ But, having people tell me that my work spoke to them is so meaningful. I want it to speak foremost to Asian women, but it’s amazing seeing other POC women who’ve connected to my work, as we all share in this similar sense of conflict.”

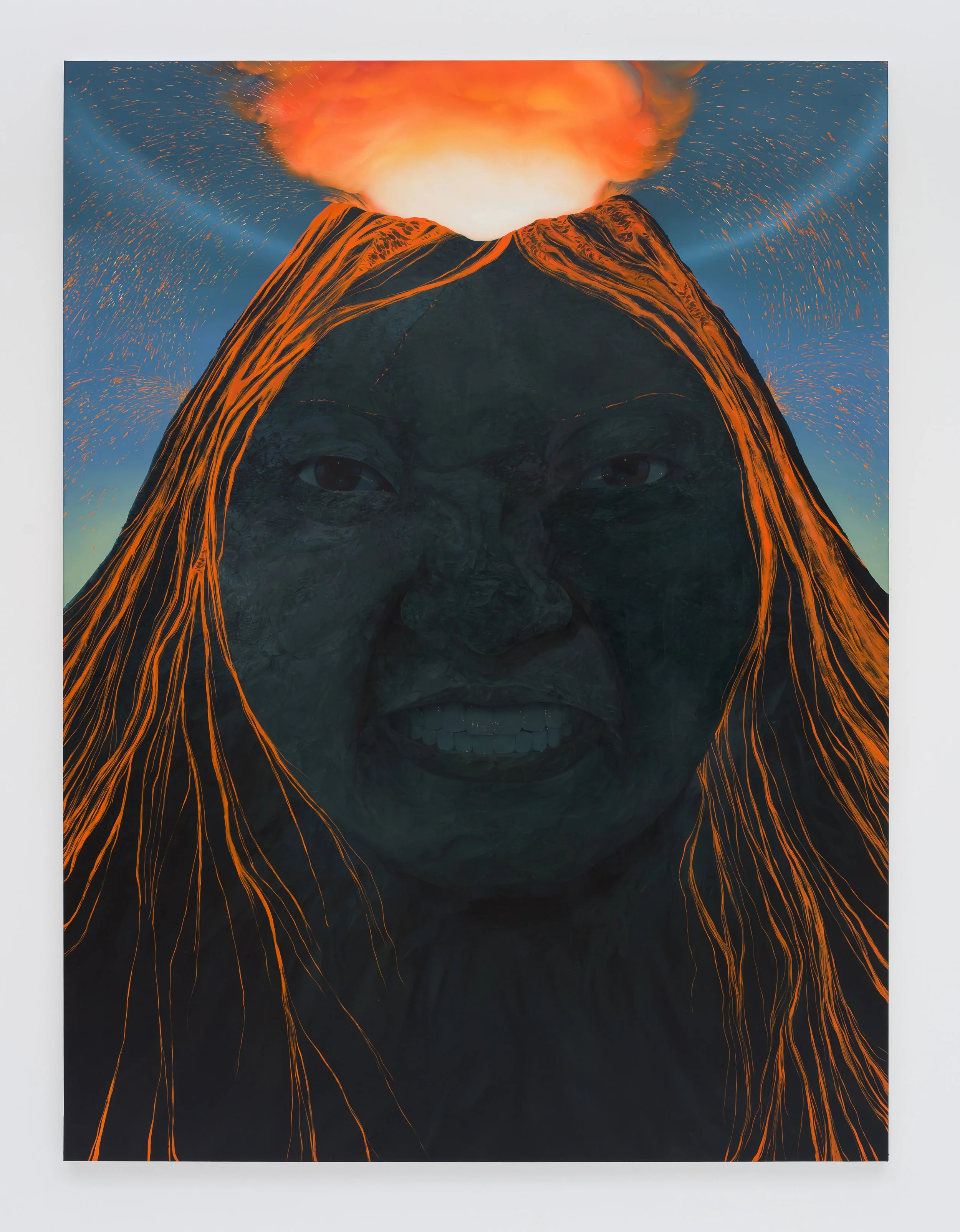

At her London show, Gordon’s explorations of the body arise from absence and metamorphosis. We see Gordon’s body transform into plants, animals and mountains. However, Gordon is always thinking of how to make her soul recognisable, even in foreign terrain – you see her mischievous spirit pop out in the glint of a tabby cat’s eyes as it perches forward playfully, its claws entangled in pink yarn, its tongue pushing forward seductively behind its canines. Elsewhere, Gordon’s face is the centre of an erupting volcano: white blistering lava set against rocky borders that crack and contour her face, thousands of years of pent-up energy on the edge of rupture.

“The transformation of my figures into these non-human forms is partly about escaping. It’s about experiencing things that have been hard to deal with as humans, so you choose to escape your body,” Gordon says. “But, it’s not been easy leaving the flesh. I wanted to show that this transformation was difficult, tense and painful.”

The tensions arise out of the vacillation between the desire for control and the need to escape: the cat, for example, is not a beast, but domesticated and made to play rather than hunt. “The cat is very queer, she’s kind of pervy – she’s playing with this yarn that I tried to make quite phallic.” Gordon’s new work, therefore, explores a new form of portraiture – of an effusive sense of self-hood, calling on mythologies of reincarnation.

I ask Gordon about what’s next, and she laughs, “Seeing my friends, having a New York summer, getting back to a normal routine. I love painting at night but it was making me a bit crazy.” Gordon loves being a New York girl. After moving to Bushwick, she met a community of artists from the Here and There Collective that’s dedicated to connecting artists from the Asian diaspora. “It’s really nice speaking to POC artists about our practices. We can talk about collectors who are weird about race. A lot of galleries are now showing younger artists of colour, queer artists, and it can sometimes feel tokenising as it’s hard to gauge their intentions, and having this community is affirming.”

Gordon’s work, ultimately, achieves a difficult feat – balancing beauty with discomfort, struggle and play, vulnerability and escape. And although Gordon is painting herself in moments of self-exposure, her faces are often looking right at the viewer, inviting you to exist with her.

Words: Cici Peng | Art: Sasha Gordon