“Obviously Doctor, You’ve Never Been a 13-year-old girl:” The Specific Epistemology of Teenage Girls

Words: Mina Shahid

Make it stand out

Recently, social media has seen a trend whereby young women share the philosophical thoughts they had as teenagers, commenting on how much earlier these came to them than they did to their male counterparts. You’ll usually see this content captioned with something like: “When a man tries to say something 'philosophical' but I had that thought when I was 11.”

A TikTok creator, Hadleyo, reacts to a video of Orlando Bloom saying, “Whenever you’re with somebody, it may be the last time you see them, so make it great” by adding “guys thinking they are being so philosophical with a thought you had at 8.” Several others (almost 1,000 or so) in the comments section come to agreement, with one user commenting, “Me at 4 learning about death” and another user saying, “like the panic attack i had surrounding this thought at 9 years old.”

This trend has highlighted the highly specific epistemology of teenage girls. In philosophical theory, ‘epistemology’ is the study of knowledge and understanding how we know things. The epistemology of teenage girls, then, includes their growing understanding – and questioning – of their place in society and their relationships with others.

In sociology and cultural theory, the ‘Standpoint Theory’ states that knowledge stems from a person’s social position, therefore suggesting that marginalised groups within society have a greater insight into social issues. These groups are positioned in a way which allows for them to be more aware of the negative aspects of society and its norms, as compared to their non-marginalised counterparts. Women, for example, have historically tackled the wage gap issue and have a nuanced understanding of how equal labour, when not equally compensated, affects their social class, mental, and even physical health.

In the specific case of teenage girls, the social conditions and expectations of women in modern day society situate them in a position where they are encouraged to reflect on themselves, their place in society and society as a whole much earlier than teenage boys. Due to the privileges of patriarchy, teenage boys aren’t inclined to conduct the same level of analysis of society as teenage girls.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

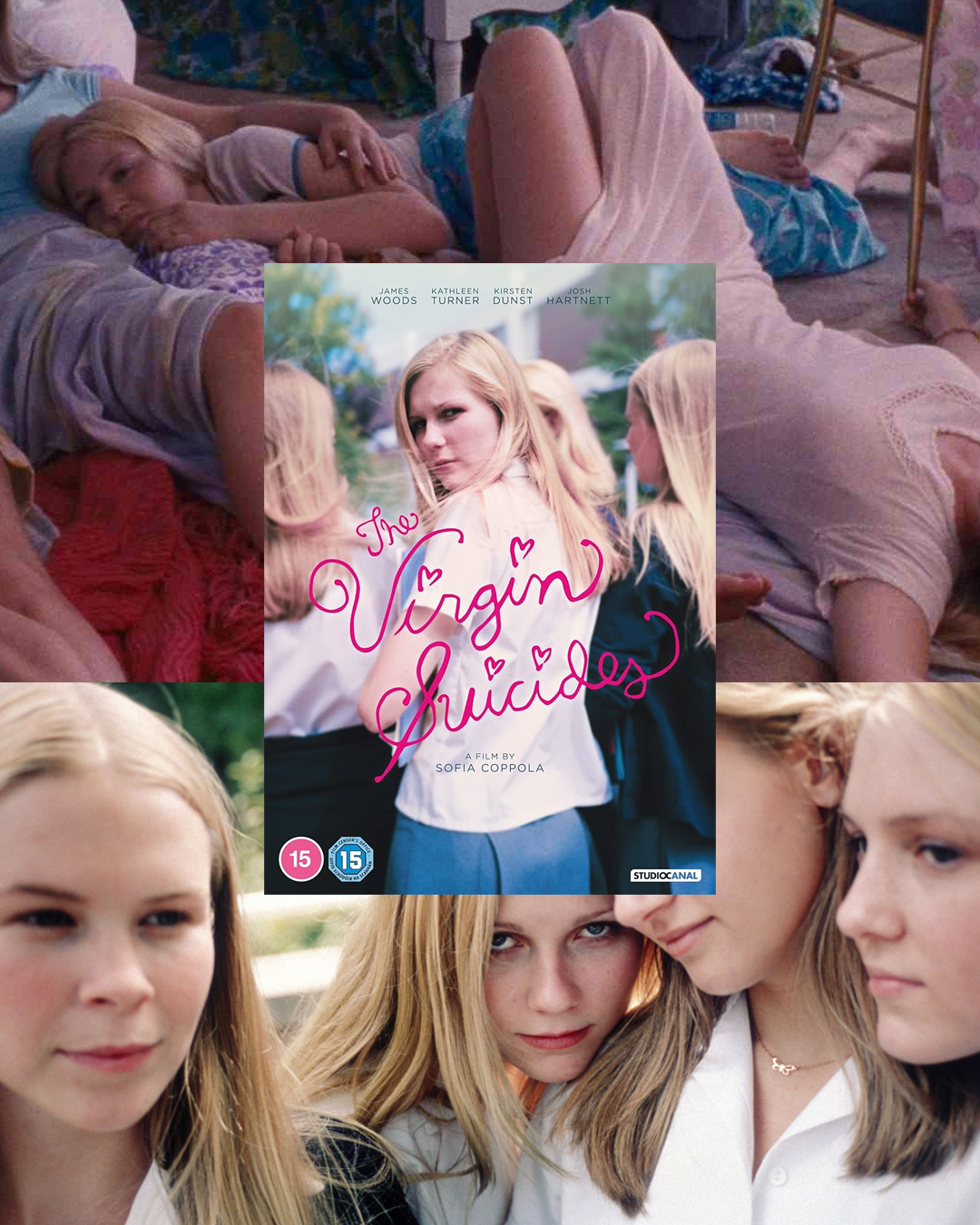

Hollywood director, Sofia Coppola, subtly and successfully portrays the particular epistemology of teenage girls in her film, “The Virgin Suicides.” The film centres on the lives and suicides of five sisters in the 70’s American suburbs, from the perspective of a group of boys who steal the diary and other belongings of one of the deceased girls.

“After all, girlhood is experienced, not explained.”

The diary, belonging to 13-year-old Cecilia, covers not only her own life and thoughts, but also the lives of her sisters. Despite their attempts to understand what drove the Lisbon sisters to their suicides, the boys fail miserably: rather than reading and attempting to understand the nuances behind her words, the boys reduce Cecilia’s thoughts to “emotional instability” and label her as someone “completely out of touch with reality,” the reason for her suicide being: “When she jumped, she probably thought she could fly.”

Throughout their narration of Cecilia’s diaries, the boys consistently gloss over things that were meaningful and important to Cecilia and her sisters, and instead start to envision their own ideal, coquette-like and hyperfeminised version of the girls. The main narrator in the film states, “We felt the imprisonment of being a girl…we knew that the girls were really women in disguise, and that they understood love.”

This suggests that teenage girls and their thoughts alone are not taken seriously – being a girl is compared to being imprisoned, and the idea that a teenage girl can have deep meaningful thoughts or an existential crisis is beyond the comprehension of the boys, compelling them to call the girls “women in disguise.” It is important to understand that while the boys are just as capable of having deeper analytical thoughts, they are not situated at the same social standpoint as the Lisbon sisters, therefore, they are unable to truly understand their lives and experiences of the Lisbon sisters. After all, girlhood is experienced, not explained.

As we see in ‘The Virgin Suicides,’ the audience is able to gauge that the Lisbon sisters felt something on a very deep level which compelled them to take their lives; but due to the story being narrated from the boys’ perspective, shrouded in the male gaze, the inner workings of the teenage girl’s mind remain a misunderstood mystery.

The specific epistemology of teenage girls is neither inadequate nor lacking in complexity. As now seen through the TikTok trend and the discourse within its comments, teenage girls develop philosophical insights about life, death, and social structures from a young age. Yet, their knowledge is often trivialised or dismissed as frivolous, be it in online spaces or in cultural narratives like The Virgin Suicides; all the while men are praised for articulating the same thoughts years later.

A trend which began as satirising men’s delayed philosophical awareness and empathy is, in reality, more than just a playful joke. It is proof that teenage girls have always been thinking, questioning, and knowing – long before the world is willing to listen.