Melissa Broder Wants Us To Suffer Together

Content Warning: Discussion of Eating Disorders

There was once a time when you and I had no anxiety. We were carefree. Melissa Broder understands this too; the epigraph to her new novel Milk Fed is a quote from the philosopher Thomas Hobbes that reads, “My mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear.” When we’re thrust out from the womb into the cold, unforgiving world: welcome, it’s time for a life of existential suffering. But it could be worse. At least we’re all forced to exist in our human bodies suffering together.

The themes of Melissa’s work as a poet, essayist and novelist cover read like a DSM entry for the affliction that is modern life: alongside fear, there is depression, the void, internet addiction, spirituality, lust and unrequited love. Her Twitter account So Sad Today made mental illness and general malaise into a 180-characters art-form. Her debut novel The Pisces was about a woman who falls in lust with a merman. Her second Milk Fed, is a novel set in LA about Rachel, an anorexic Jewish woman in her twenties who lusts after a larger Orthodox Jewish woman, Miriam. Miriam introduces Rachel to the joys of frozen yoghurt with toppings – a lot of toppings – while for Miriam, Rachel represents living freer in another way, unconcerned by heteronormativity. It’s a sensuous and tender story about searching for meaning, relinquishing control from the matriarch and eating both pussy and food well.

When I video-call her, Melissa’s dog-child Pickle is milling around the room rather than sat in her lap where he usually is while she’s at a laptop. This is probably for the best because we’re about to talk about mommy issues.

HE: As a proud owner of mommy issues, I appreciated that Milk Fed is all about them. We know all about daddy issues. Why don't we talk about the former? Are they more taboo? Is it a matter of respect to the mother?

MB: I too have noticed that I hear a lot about ‘daddy issues’, a common phrase. Although I will say that the other day I was on this website called Redbubble, which has the best stickers. I love stickers and like to make collages online to relax me, so I was looking and I was like, 'I wonder if there are mommy issues stickers?' And there were! So they are enough of a thing that there are the stickers. But, I don't know – is there something sacred about the mother that one might be afraid to bring that up? I guess from my own experience, they are scary to divulge, knowing that my mother could encounter me talking about this stuff.

HE: It goes the other way with women not wanting to talk about regretting having kids. That's a different question but exists as a part of the mother as sacred idea.

MB: Yes! I don't have kids, thank God. I'm very peaceful about that decision. But there was a period of time where I always knew I didn't want them but wasn't confident that it was an okay decision. I was like, 'Well, what if I have regrets?' And I remember talking to a therapist and being like, ‘Well, my mom says to me once you have them, you'll want them.’ But my therapist is like, 'That's not true! There are women who come to me who are like, what the fuck have I done.' But we don't hear about that, right? The woman who does not want her children is villainized.

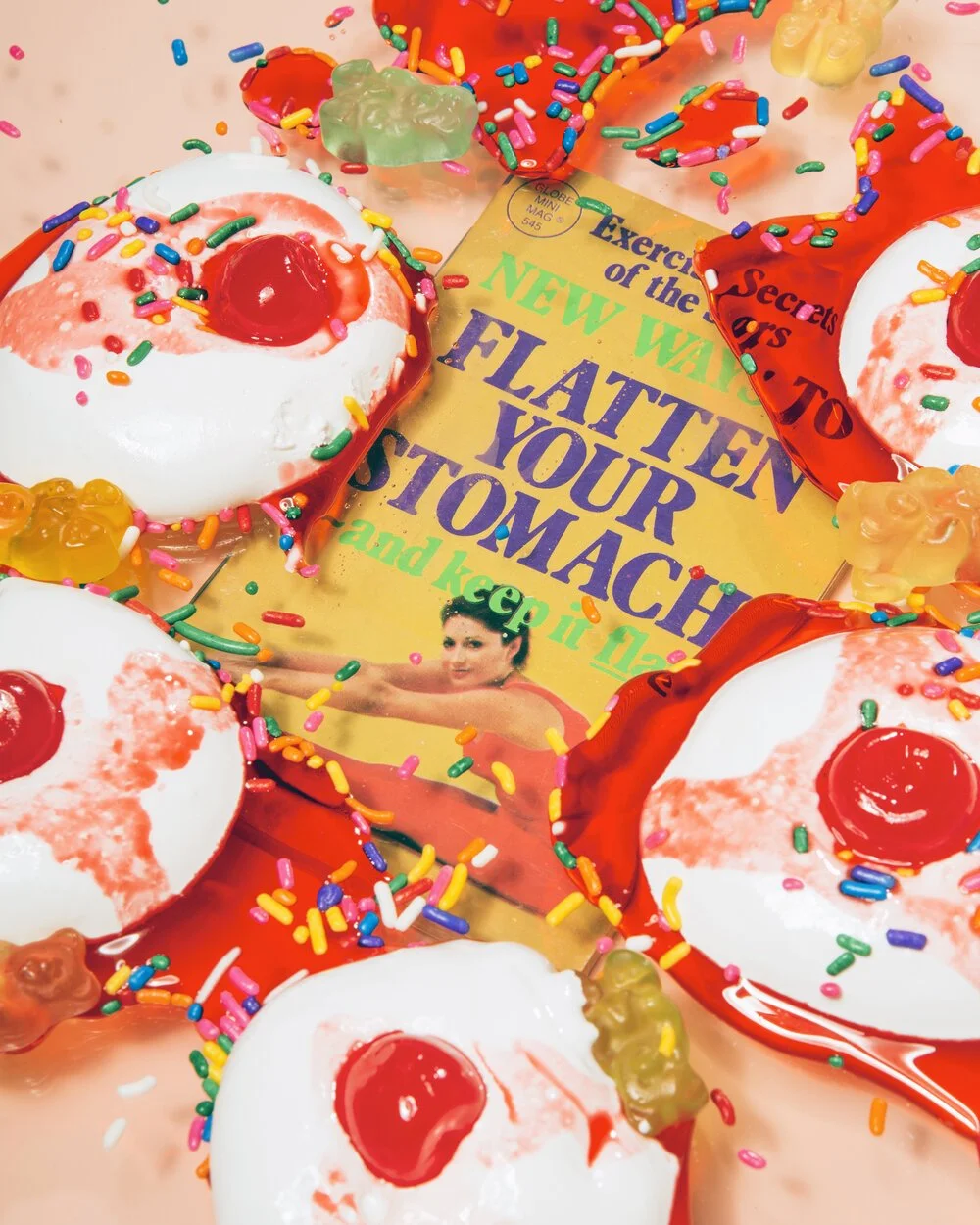

HE: Rachel, who clearly inherited food issues from her Mother, has these thoughts about consumption that are painfully accurate to anyone who has had control issues around food. The calorie count of different foods, for example, are something that you never forget. It’s like recalling the date of Great Fire of London or your own phone number. Did you feel like you knew this information so well you thought it would be perfect to explore through a character?

MB: 100%. When you have an eating disorder, it's a full time job, right? It's both job and hobby and passion and love and hatred. It's…your life. So having had eating a severe eating disorder in high school, this is information that you don't get rid of. I have friends who grew up Catholic and they no longer practice but they still have the guilt and for me, that's it. Once you've had the religion of an eating disorder, even if you've recovered to some extent or you're in recovery, this knowledge does not just go away. I have a PhD in this information that I do not need. So all the research had already been done. But it's its own world. And so if literature creates worlds and is world building, well, this is a world I know very well.

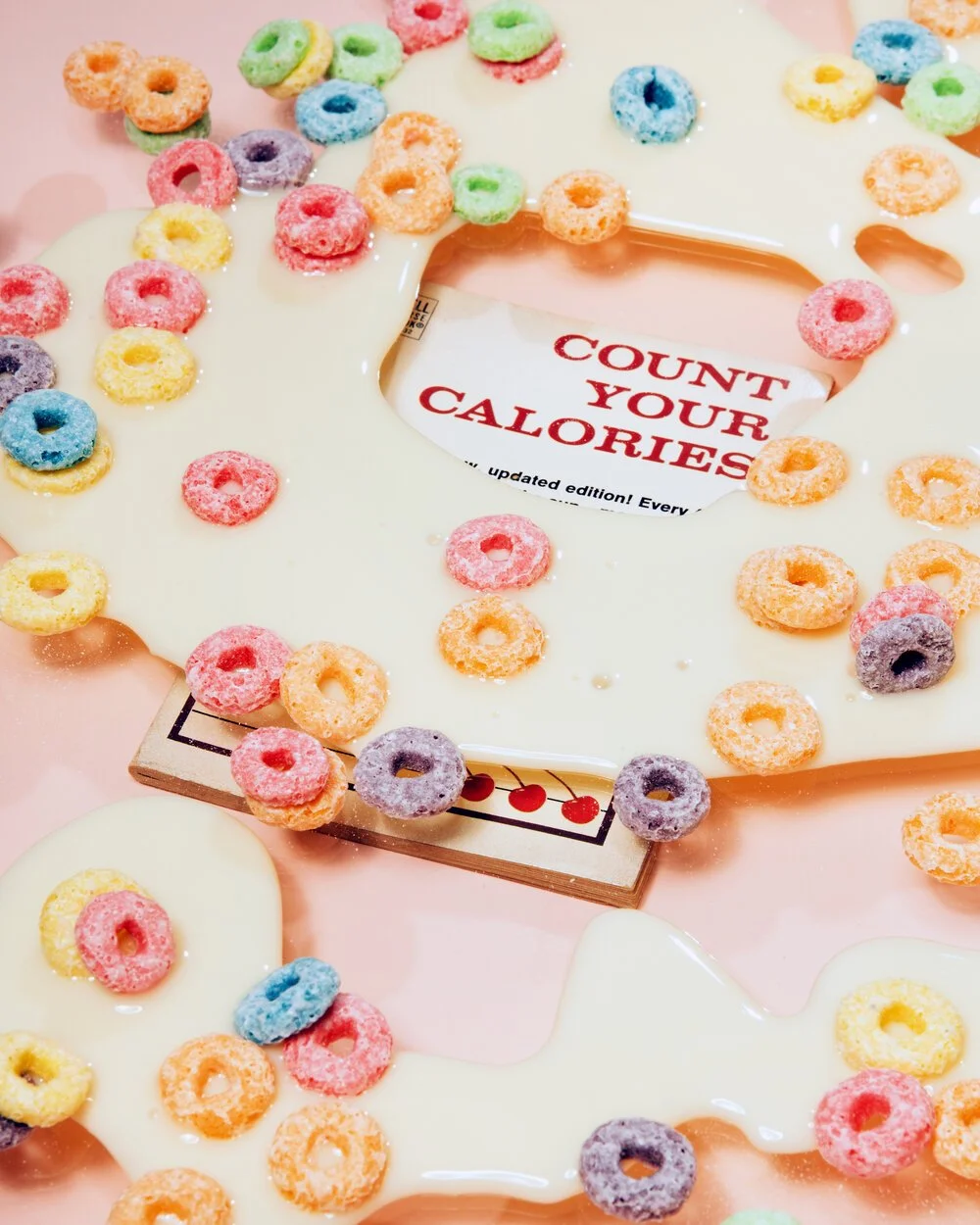

HE: And you crafted it so well. But what balances that restriction and suffering out in the novel are all the sensuous descriptions of the food. I was constantly salivating. With The Pisces you used Siri to dictate the first draft. Where you dictating all these descriptions of the food?

MB: So the first draft I did dictate the whole book. However, I probably spent more time editing Milk Fed – at least 40 or 50 rounds of edits – than I've ever edited anything else I've ever made. A lot of the descriptions of food that you're reading, there's probably not all that much of the original dictation. Every sentence was combed over. With The Pisces my editor was like, ‘okay, we can have her washing her ass less. We don't need to be with her washing her ass twice.’ But that's why you need an editor to refine and hone it in. With Milk Fed and the frozen yoghurt shop she was like ‘get your best toppings in this paragraph. You don't need four different paragraphs’.

HE: That's funny. What are your favourite go-to desserts when you want luxury and fantasy?

MB: Well, my favourites are definitely when Rachel has her bakery bingeing scene. But definitely carrot cake with cream cheese frosting. An M&M’s chocolate chip cookie the size of my head. Nothing with fruit in it – give me the chocolate and give me the cake. I also love just a tub of frosting. I'm from Philadelphia originally and there's these things called Tasty Cakes, and I really love butterscotch Tasty Cakes.

HE: Food, sex and this idea of nurturing or being 'mommied' blur throughout the whole book. Rachel, has these sexual fantasies about the MILF at work Ana but also wants to be nurtured and breastfed by her. Do you think that it's healthy for these urges of sex and parenting blur? Or is that just the reality of being a human being?

MB: To me I think it’s the reality. I feel as though we're often encouraged to compartmentalise our appetites for hunger, sexuality, spiritual longing and familial yearning. We're encouraged – I think especially as women – to see these things as separate but to me they are all connected. I also think that our parents are our first gods. Every faith has ideas and judgments about pleasure. So if our parents are our first gods, we're going to absorb a lot of our ideas about pleasure from that source. I think for Rachel, in order to feel permission to experience pleasure, she feels like she needs that godly aka maternal permission. In that first sex scene fantasy with Ana, Rachel says, 'I am the innocent one here.' Like, it is God/Ana who leads her into it so it's safe for her.

HE: I was thinking before this conversation: what makes Melissa Broder's sex scenes so good? I realised it’s partly because they're all fantasies, right? That's where you can access the real good shit.

MB: It's psychological. So much sex is about us, it's about ourselves. I've had a lot of sex and I'd still say that the best sex I've ever had has been with myself because I create the entire world. I get to completely vanish into a world of my own creation. And maybe that's about control. I'm sure some people will be like, that's weird. It doesn't mean I don't want to have sex with others (I have certainly pursued that). Sometimes the sexiest word in our fantasies is not a word that one would think is sexual word, but we have that word. It's kind of like the opposite of a safe word.

HE: What are some of your favourite sexy bits of writing?

MB: I'll tell you some contemporaries and I'll tell you some olds. Garth Greenwell's Cleanness. Andrea Lawlor's Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl. I'm a huge Marguerite Duras fan but it's funny because her books aren't super explicit. It's actually much more about longing. And then James Joyce's letters he wrote to his wife Nora. The fart letter is fabulous. I love the fart letter. As a poem, Gertrude Stein's ‘Lifting Belly’ is great. And I really like the scene in Call Me by Your Name in the hotel where one of them is shitting and the other one helps him shit. I find that very beautiful.

HE: Oh, I completely forgot about that bit from the book.

MB: The peach scene is nothing. Fuck the peach scene.

HE: I loved that Rachel self-defined as bisexual. There’s something weirdly retro about that word in culture now. Whenever there's a time which I have to say it, I'm just like, should I say pansexual? But I say bisexual because that's what I said when I was like, 14, on the internet.

MB: I feel like pansexual really much more accurately embodies how I feel. You can be pan but I feel like I'm old and people are just gonna be like, 'Get the fuck out of here.’ I guess bi means something very similar. Bi doesn't just mean two genders. It's like, all genders, but I guess just by the nature of the word bi, it does feel to me that it sounds more limiting than pan although I know some Tumblr kids would get mad at me for saying that. I think for me, actually, ‘fluid’ is probably the most accurate. It feels more grown up.

HE: Total gear change: I know that you meditate and have spoken about leaving your New Age youth behind you somewhat. Do you ever fully indulge in that world or does it prang you out and take you down a bad path?

MB: I like to keep that stuff in the realm of play and creativity. I have crystals and I think they're fun. And I have this box that I call my God box [Melissa holds up a shiny box the size of a large candle that I later remember as sparkly with crystals on it but that could just be a fantasy] where I just put my fears or things that I'm obsessing about to try to just relinquish them. But I can also find myself then becoming very spiritually materialist, and getting obsessed with whether I'm using the right crystal. In my 20s I was definitely actively searching outside myself for some kind of answer, and now I believe that it's already in there. And I don't need more crystals, I actually need less stuff.

I see these things as a way to sort of catalyse new ways of thinking, but it's not about the actual thing. I forget the expression but it’s like if someone is pointing to the moon, we’ll be staring at the finger. If the finger is the religion, it’s like no, it’s pointing to the moon. We get so attached to the finger. I can say a prayer on a candle and let it burn all night, and then in the morning, throw away the stub and be like, OK, the prayer has been done. But that's more about praying to create a shift in perception for myself. I’m using the spiritual tools for internal shifts and kind of accessing what's already in there, just buried.

HE: You’ve written beautifully about being in an open marriage and it’s now closed. What do you think is the magic of monogamy? I know that there must be magic in both but it feels so much easier to see the promise and charm of non-monogamy. I need the answers.

MB: It can still be disappointing to me that a 'healthy' long-term relationship is hard to get high on, in the way you can with a stranger or a fantasy or something new. I think the beauty of a long-term relationship is when it goes in cycles, and when you ride out those cycles, you suddenly see this person you've been with for so long, completely new. You remember that they are a separate person, and you see them with new eyes. That's its own kind of magic. It's inevitable that we're going to take whoever we're with long term for granted. There's no leaping, there's no achieving, it's not about obtaining, it's right there. But to be able to circle back around and see that person as new, which does happen and can happen in long-term relationships, and to like re-fall in love, over and over. There its own kind of quiet magic about returning again to the same person and seeing them as new.

HE: I like the acknowledgment that relationships – like your growth, your career or pretty much anything else – do not exist on a linear timeline. It’s never reinforced to us that life works in cycles.

MB: And we can't expect a long-term relationship to be bigger or stronger than our desire for the new. Just because we desire the new while in a long-term relationship doesn't mean there's anything wrong with the relationship. It sucks that love is a verb. It’s annoying. I want love to be a feeling all the time. But that’s the type of love that’s presented to us in art, most love songs are not about [Melissa puts on country voice] coming home to my woman after twenty years. It’s the beginning or the end or the distant. There aren’t any ‘I’m going to Boots, do you need anything?’ love songs. So of course when you’re in a Boots relationship you’re still going to crave the non-Boots non-knowing non-comfortable because it accesses a different part of us. But it doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with the Boots relationship that we’re craving a non-Boots.

HE: That’s wise.

MB: But I’ve only learnt that through experience.

HE: To me the real beauty of this novel is in the way that Rachel and Miriam have these changes in perception, just as you say you now look for in your spiritual life. What have been the biggest shifts of perception in your creative life?

MB: Two things. Firstly with this book I kept thinking I was done and then an editor would be like ‘ok, one more round of edits’ and I’d think it would be an easy edit and I’d have to go back into the weeds. I’d have a nervous breakdown and be like I can’t believe she’s sending me back into the weeds. I thought I’d be doing little prunes from outside the weeds. Then I go into the weeds and I love the weeds. I’m happiest in the weeds but when I’m not in the weeds they seem so daunting. Again, it’s a process of remembering. That could also be said of feeling deeply. When I’m holding back a feeling or repressing it, I’m so scared of feeling but when I’m in the feeling I’m like this is what life is, this is so deep. It’s about control and wanting tidiness and neatness. I learnt that through creating things.

The other thing is that I write to be in control of the narrative but even when we’re writing we’re not totally in control. The poet Muriel Rukeyser said that “you need only be a scarecrow for poems to land on”. I do think as a writer you have to show up and be there for the stories to land on but there’s an alchemical process that has a magic to it. One personal lesson I learned from being a writer is that I do have to show up and put in the work but that I am not in complete control and that’s true of life. I gotta show up but I’m not in control. You have to leave room for the magic and the miracle.

Words: Hannah Ewens | Photography: Elizabeth Renstrom

To Support independent feminist media, join our Dollhouse Platform. The first thirty days are free!

Milk Fed is the second novel by Melissa Broder and is out on 4th March, you can pre-order a copy here.