Intimacy Through The Looking Glass: How the Internet Changed Our Experience of Relationships

Words: Eugenia Perozo

Make it stand out

“It’s like being in a relationship with two different people, it makes me so anxious.” By all real measures, Ana*’s relationship with Max is strong. But for Ana, who grew up in the social media era, this is not always enough. Max is a ‘bad’ texter, and the anxiety this causes her is sometimes so big that it taints the happy, in-person moments of their relationship. Is this normal relationship anxiety? Or does the language of digital closeness have a stronghold on Gen Z’s experience of intimacy?

We often hear about the loneliness epidemic among the young. At this point, we also take it for granted that there is a correlation between the rise of social media and growing isolation for young people. The problem is not just that technology has fostered distance between peers in an IRL setting, but the role that social media has had in defining the way we relate to our friends and loved ones.

The early 2010s for a girl was overwhelming; there was Snapchat, Tumblr, Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, AskFm, Youtube, Skype, and the - not yet so derided - phone call. Famously teenage years are filled with insecurities, particularly for women and girls: adolescence claws at a sense of self to be afforded safety and identity. And back then, we were given so many ways to claw, dig and cultivate ourselves. On our phones, we could change what we looked like physically but also curate the ‘cool girl’ version of ourselves we aspired to be, and while our identities and experiences were shaky in real life, the digitally curated versions of ourselves beamed back at us from our phones. Feeling, then and now, just as real as our physical bodies.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

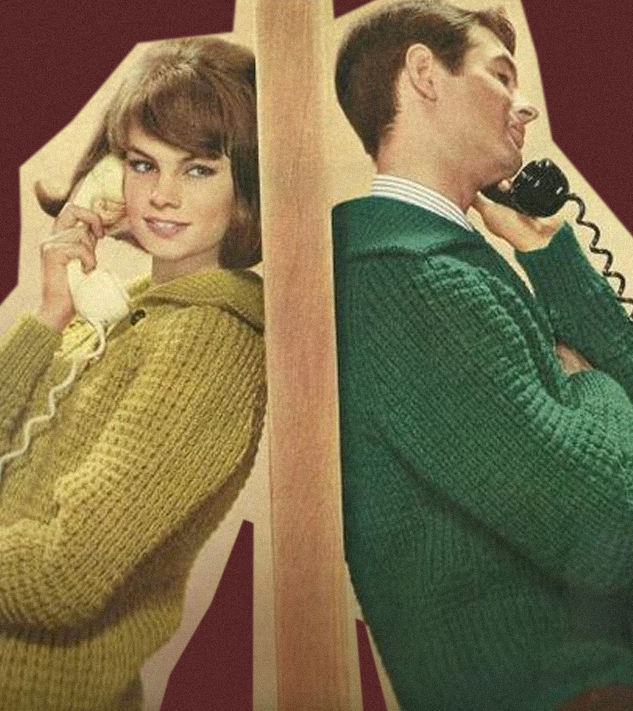

It was amidst all this that we redefined intimacies with friends and loved ones. Now, for millennials, gen z and younger, there is far more work to be done to upkeep personal relationships. First, there is the elaborate birthday post. Then, Snapchat streaks, the numerical marker of true friendship. I don’t know anyone my age who doesn’t know about a nude scandal that ruined a young girl’s life, leaving the boys and the culture that made them unscathed. And then, the ridiculous back and forth after meeting someone you liked: You could give them your Instagram, but not your number. You could send them a selfie, but no more than one text at a time.

“It seems that the biggest effect that social media had on our experience of intimacy was making us believe that it was a public affair.”

And even if some part of you had an inkling there was something off about this, it would be impossible to carve out a new path of romantic communication when everyone else is following a different rulebook.

Andrew*, a 22-year-old who has mixed feelings toward social media, has felt this way before. He admits to a contradictory logic towards public displays of affection and says that while he doesn’t like being pressured to post with his partner, he struggles to be indifferent about how others post about him. Andrew explains, “If she doesn’t repost a story I post with her, I would question if she wants to be with me.” Then, he asked me with genuine curiosity, “Do you think that you have to be compatible online and offline nowadays? And if you’re not, is that a reason to break up with someone?” A new question for digital dating has arisen: if I don’t feel the same for someone’s online presence as I do for them in real life, is the connection even real?

Meanwhile the negative impact that technology has on developing minds is gaining political momentum. There is also no shortage of information suggesting that when big tech companies knew the negative effects they were having, they decided to look the other way. But even if there is a public policy overhaul that manages to save the next generation, we are all, already, begrudgingly, hooked. As Andrew’s testimony suggests, it’s not that we don’t see how technology harms us, but that these practices are so ingrained in the social fabric that we feel helpless towards them.

Oxford Professor Carissa Veliz worries about the lack of privacy that the age of hyper-surveillance has brought upon us. In her book, Privacy is Power: Why and How You Should Take Back Control of Your Data, she says, “There is no intimacy without privacy — relationships that cannot count on the shield of confidentiality […] are bound to be more shallow.”

Our society and our economy’s need for us to value the online world so much (not to mention the addictive nature of these platforms) makes it hard to opt out of the shallowness. It’s a contradictory promise. Post with your partner and your love will be even more real. Text someone all day, every day, or you’re not really that close.

Giving as much validity to our online interactions as we do to our physical ones creates a false equivalence that cheapens our relationships. Just like posting a flurry of infographics for a cause is not the same as going to a protest, sending someone memes or having a slow-dotted conversation through text is not the same as in person quality time. Breaking out of this experience of intimacy does not just mean finding each other in real life, but knowing that this has categorically more value. Not only because it creates space for a deeper connection, but because it’s not putting money in the pockets of those who created this mess in the first place. By taking the digital performance out of our intimate relationships we may find that we don’t only not feel so lonely anymore, but far less helpless.

*Names changes for anonymity