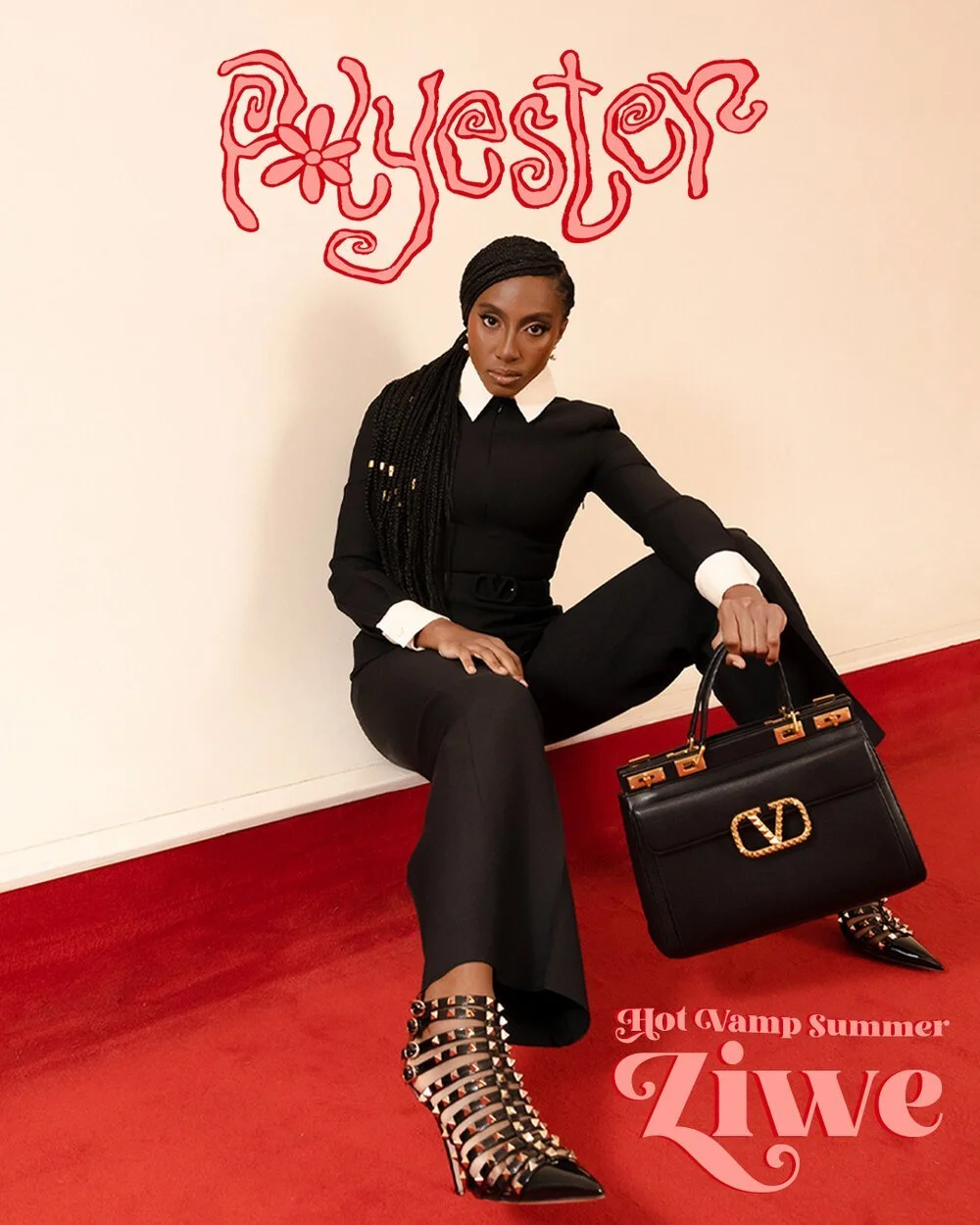

How Ziwe Revolutionised The Interview Format

Make it stand out

The Summer of 2020 was brutal for Black people everywhere. From the murder of Ahmad Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Dominique Rem’mie Fells, and countless others, it felt like death was hovering around every corner. Around this time, I was physically and mentally exhausted. I did not know how to deal with all the death, pain and sadness. However, Ziwe Fumudoh’s comedy show Baited, which she moved to Instagram live from Youtube, brought levity during a time when it felt difficult to laugh. Ziwe explained in a Vanity Fair article that her ultimate goal with her Instagram live show is to have “a good discussion about race and entertain people.”

The comedic elements of her show do not negate the fact that Ziwe is also educational. Each episode of the series (now renewed for season two) is based on a theme. From White womanhood to immigration and white-washing, a great deal is covered. Episode two explores beauty standards, as we saw Ziwe take a trip to see a plastic surgeon — with him awkwardly suggesting that she can “refine” her nose. Speaking to Ziwe, she explains that unlearning White supremacist notions of beauty is a “practice that you have to learn every day.” She expresses that: “when I was growing up, Naomi and Tyra Banks were rising as supermodels. Naomi was the first instance of me seeing a dark-skinned woman on the cover of a high fashion magazine. Naomi Campbell was a massive influence on me understanding that I was beautiful.”

As soon as Ziwe mentioned Tyra Banks, I instantly thought of America’s Next Top Model (ANTM). I used to binge-watch episodes with my little sister, and it was the first time I saw Black girls of different shades and complexions in one place. Ziwe shares my admiration for ANTM, telling me, “ANTM probably taught me the foundations of studying your face and knowing your angles. Do you remember the go-see challenges? I'd cross the street in Times Square and make sure my stride is perfectly timed! I think a lot of people who were into that show can relate to that.” As someone who used their mum’s treadmill as a catwalk, I can definitely relate.

“I do not have any qualms about anyone who has a lot of opinions. I think that those are the people that thrive on my show.”

From Phoebe Bridgers to Caroline Calloway, Ziwe has spoken to a lot of White people; but confesses that she’s not sure if she’s learned anything new specifically about Whiteness. “To be honest, I spoke to a myriad of different people. I think every single individual on my show brought something different. Whether that was talking to Fran Lebowitz, talking to Andrew Yang, or talking to Stacey Abrams, I approached every interview ready to listen actively and receive what they're saying.” Ziwe’s interview with Fran was something my friends and I raved and ranted about. After watching and then rewatching Pretend It’s a City (2021), we were stans. We wanted more Lebo! Ziwe also loved interviewing her, “What an interesting perspective she brought. I really appreciate her doing an interview with me. Originally, she said she'd only do 30 or 45 minutes and then we ended up talking for two hours! I do not have any qualms about anyone who has a lot of opinions. I think that those are the people that thrive on my show.”

With Ziwe gushing about Fran (admittedly prompted by me, who initiated the gushing about Fran), I had to ask her who her favourite and least favourite guests were on the show. “I don't have a favourite or least favourite guest,” says Ziwe confidently. “It's like having a favourite or least favourite child! Every interview gave me something different. The interview with Eboni K. Williams was really exciting because I got to talk to a Black beauty queen who was also on reality TV. That was really niche and different. We also spoke about her experience with Fox News, which I was intrigued by because I didn't really understand. Conversely, I talked to someone like Andrew Yang, a mayoral candidate, so you have real-time knowledge of what this big American politician is thinking, and that's really compelling. Versus me talking to my friend Julio Torres that was really fun because we really got to play with the show’s editing. That was really important to me because they're a comedian. So I believe every interview is different. I don't have a favourite.”

Ziwe’s show shares many similarities with research I found for my dissertation on the celebrification of activism in the 70s. In 1970, writer Tom Wolfe wrote an essay for New York Magazine titled 'Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's'. It was a critique about white celebrities who endorsed leftist radicalism to lessen their white guilt and advance their social standing. Ziwe (the show) explores the same critiques regarding performative activism and allyship. I ask Ziwe if this surprised or shocked her, “I think history has a way of repeating itself. So I'm not as familiar with Tom's article, and I can't speak to the exact parallels of the 70s and now. However, I can say that the show came from observations I made in my lifetime in America, so if you feel as though there are sort of motifs that continue to repeat themselves in culture, that is simply because of my observations from when I was five and then 10, and then when I was 13, and then 20.” To paraphrase Angela Davis, the past really isn’t the past; it’s always present.

Intrigued by my dissertation topic, Ziwe flipped the script and started asking me questions: “What was your dissertation specifically on?” asked Ziwe, I responded, “Well, I investigated Angela Davis and Kate Millett. So I looked at the celebrification of radical American feminists in the 1970s and generally the celebrification of activism in that time period.” She then asked, “What was your takeaway?” I passionately explained that “The media sucks. They love to make a complex movement about one person so they can tear down a person and then tear down their movement. For example, the media labelled Kate Millett, the leader of the Women's Liberation Movement (WLM). Then when they found out she was a lesbian, the press used that to discredit the WLM and labelled them as men-hating lesbians. When it came to Angela Davis, they vilified her Blackness and discredited her intellectualism using racial stereotypes. By doing this, the media painted both communism and the Black Panther Party as aggressive and threatening.”

“My show discusses celebrity and whether that's good. Whether these people have any merit, other than the fact that they have symmetrical faces and television shows.”

Ziwe was interested in my dissertation topic because, in addition to her show being about activism and its performance, it is also about “the deconstruction of celebrity culture.” Ziwe gives me a history lesson explaining that “Even in the 80s, we had celebrity politicians. So my show pays homage to the daytime talk show and it’s host, but it is also about the ways in which celebrities use and exploit certain types of movements to personally profit. So, just as your dissertation is about the centralisation of movements in order to deconstruct them and render them invalid, my show discusses celebrity and whether that's good. Whether these people have any merit, other than the fact that they have symmetrical faces and television shows.” When I started researching for my dissertation, I was convinced that this whole celebrification of activism was a new thing. I used to think that activism was so pure in the past, and it was a time in which we weren’t making people icons or using social justice for clout, but it’s clear that celebrification has been a part of activism for a long time.

Something that Ziwe finds particularly complicated right now is “the confluence of celebrity and politician in the last four years.” She explains, “Politicians like AOC or Bernie Sanders have become global superstars, and we know their greatest hits: universal healthcare, etc. Additionally, they have millions of followers, more followers than a lot of actors. Even pop stars who used to be somewhat apolitical are now expected to make political stances and state who they are voting for. There's now a fear of losing money and losing listeners if they don’t. After the last president, I think we are watching the merging of the two genres, and my show also explores that idea.”

Ziwe brings up a good point. More and more people want celebrities to be activists and speak up against injustice. Sometimes though, we need to ask ourselves if said celebrity will add anything necessary to the conversation. Are they educated enough to use their platform in this way? Or do you just want them to prove themselves to you? “I’m really intrigued by celebrity culture because that’s the closest thing we have to royalty in America,” asserts Ziwe. “I wonder, why are these people’s opinions of value to us? Other than the fact we like the characters they play? Do they owe us that information?”

I could have spoken about the history of celebrity culture with Ziwe all day. But instead, we wrapped up our chat discussing alternative universes and our alternative selves. In an alternative universe, Ziwe thinks alt-Ziwe is “possibly a civil rights lawyer or professor.” Ziwe, who studied African American Studies at Northwestern University, wanted to be a lawyer but loved her course too much. “African American Studies was the first time I felt connected to what I was learning. So I've always wondered how do you make it applicable to the everyday man. My goal with my art, while it is very niche, is to use that education and make what I learnt accessible to people who don't have $200,000 degrees. The majority of people in America don't go to college. Only 32% of Americans go to college. So I think about how I can reach regular people. How do I take the skills I've been blessed with, the institutions that I've been lucky enough to be admitted to, to the common man.”

Historical education for Black people or people of colour can be heartbreaking. But it can also be extremely liberating. There’s so much empowerment in knowing your history, knowing your past and learning why the world is the way it is today. To not share that knowledge with other people feels like a crime. This is why I’m particularly grateful for creatives like Ziwe, who want to share what they know, and make people - particularly Black people - laugh while they do it.

Photography: Enmi Yang | Writer: Halima Jibril | Styling: Pamela Shepard-Hill | Hair: Cheryl T Berhamby | Makeup: Merrell Hollis | Production: Camille Mariet and Jacob Sefarian

Reserve your free print copy of the Hot Vamp Summer zine here.