Girlhood Lore: The Exhibition Exploring the Art Behind the Bows

Words: Alice Gerosa

Make it stand out

If 2023 was dubbed “The Year of the Girl”, 2024 proves that girlhood remains as relevant as ever. Even with another sad-girl autumn fast approaching, it’s clear we’re not quite ready to pack away our ribbons and ruffles. Yet if to make something more appealing, you just have to put a bow on it, the ever-growing wave of girl-centric trends has blurred the lines of defining what girlhood really means.

Contrary to marketing's wishful thinking, girlhood isn’t a monolith. Even in fashion, where trends are most codified, not all bows are created equal. From Simone Rocha to Sandy Liang, from Selkie to Rodarte and Alessandro Michele’s recent and already iconic Valentino collection, feminine and “girly” aesthetics have taken different forms.

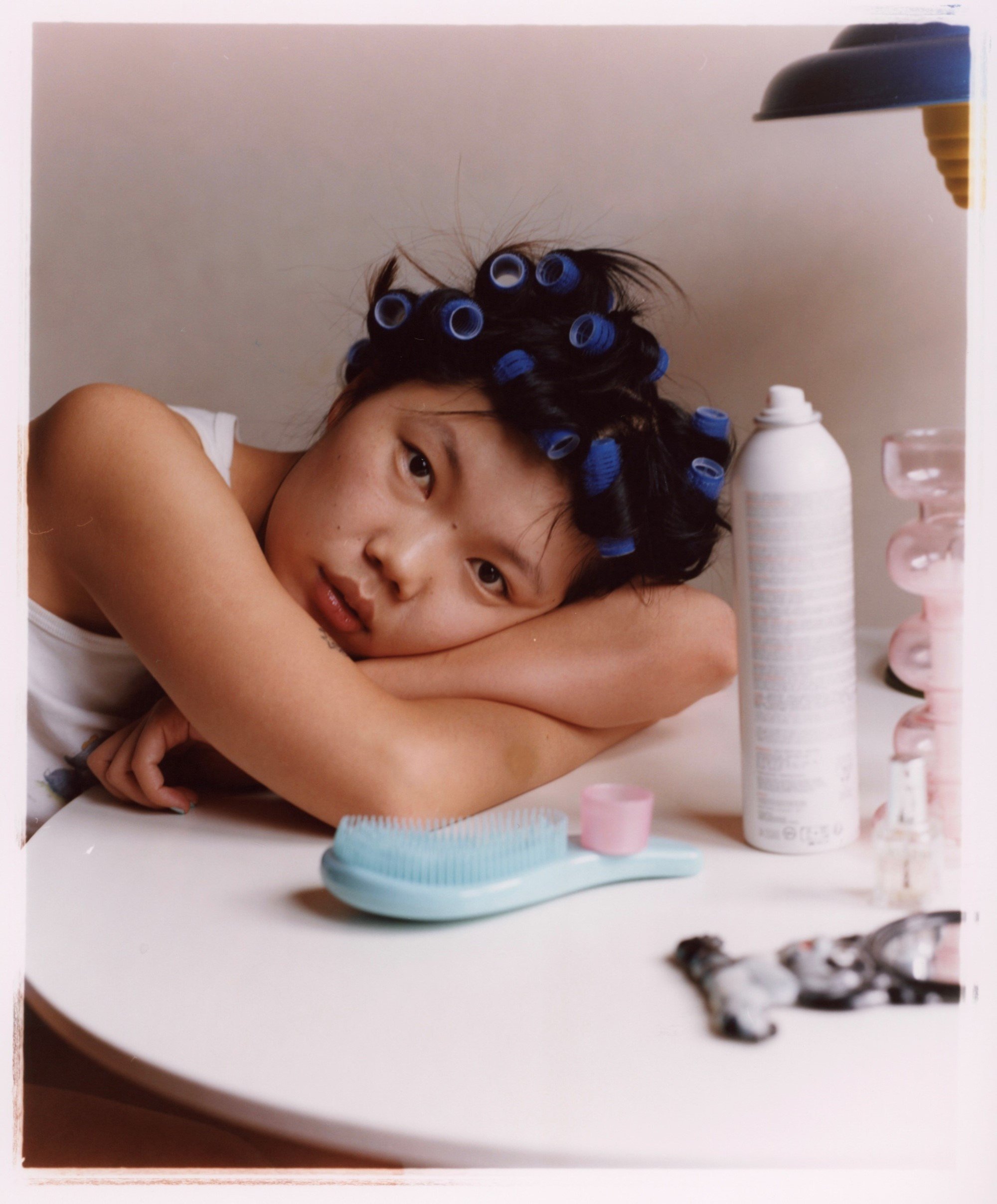

Ramona Jingru Wang, “Echo” (2023)

This plurality is even more apparent when it comes to the arts, as demonstrated by Girlhood Lore, curated by Laura Rositani for Mulieris. The exhibition brings together seven artists in an engaging and thought-provoking showcase of the different ways in which girlhood can be lived, imagined, and dreamed. What ties together the various artworks, explains Greta Futura Langianni, founder of Mulieris and ideator of the exhibition, “are not codes, or an aesthetic, but a sensation that has been elaborated in different ways”.

Danish artist PILAT (Pil Anna Tesdorpf) and Japanese artist Yufi Yamamoto, for instance, immerse their female figures in colourful, retro landscapes. Togolese-German photographer Delali Ayivi explores her diasporic identity through dreamy, curated images of girls with butterfly wings, while Inès Michelotto’s multidisciplinary approach focuses on the body and the transformative nature of girlhood. Berlin-based Lucia Jost captures intimate, everyday moments of young women, often highlighting the communal aspect of growing up as a girl.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

New York-based photographer Ramona Jingru Wang draws great inspiration from the media she consumed growing up, particularly from “the romantic girlhood friendships” depicted in Taiwanese and Japanese films and shows. She didn’t realise how deeply her work revolved around the idea of girlhood until people began to point it out. Still, she recognises that her memories and experiences have been ingrained in her practice from the beginning. "I didn’t grow up in a very gendered way," she notes, "but I’ve always been taught to appreciate femininity and the strength that comes with it." In her ongoing mockumentary project, My Friends Are Cyborgs, but That’s Okay, she imagines “a world where Asian bodies navigate as cyborgs in a hegemonic human society. It explores the complex state of being cyborgs and Asian — fluid, transgressive, marginalised but also stereotyped as unemotional and inhuman”.

The work of DaddyBears, on the other hand, aligns perfectly with the trends that revolve around girlhood. With an ultra-feminine aesthetic and a nostalgic quality, the British textile artist seamlessly evolved from playing with dolls to creating wonderful pieces whose hyper-femininity, softness, and pastel colours reminisce of the objects found in a typical girl’s bedroom. Her exhibition piece, Surrounded by Angels, is a “napping chamber”, an interactive space composed of four satin panels, tied together with ribbons, in quite a fragile way that reflects “the bonds of friendship”.

Lucia Jost, “Karla and Maya”

“‘Hyper-feminine is not only considered lesser,’ the artist notes, ‘but the further it pushes away from the ‘serious’ ideas and works of men, the more threatening to traditional views it might seem’ - is now extremely popular, this popularisation and subsequent commodification can further devalue it.”

In art, girlhood can take many forms, as this exhibition demonstrates. When it comes to the mainstream, however, the representations pushed to the forefront are much more codified. DaddyBears is aware of this, noting that her Instagram feed is inundated by images that “just mirror back my own aesthetic”, in an echo chamber that can be uplifting but also daunting. If it’s empowering to know that an aesthetic historically deemed frivolous - “hyper-feminine is not only considered lesser,” the artist notes, “but the further it pushes away from the ‘serious’ ideas and works of men, the more threatening to traditional views it might seem” - is now extremely popular, this popularisation and subsequent commodification can further devalue it.

DaddyBears, "Surrounded By Angels"

Overall, the pros seem to outweigh the cons, especially when it comes to gaining an audience that appreciates your aesthetic and your craft: “I think if coquettecore wasn’t so influential currently, I would maybe find it harder to feel comfortable completely immersing myself and my practice in the visual language that I use. That being said, I think I would still be making the exact same work, it would just be less popular”.

There is one common thread that connects these diverse representations of girlhood, whether in nuanced artworks or TikTok trends: they feed into a deeply ingrained feeling of nostalgia. But what is it that we are longing for? The simpler times we lost, or rather an idealised version of them? For Ramona Jingru Wang this longing is “based on real moments, but they might not be a permanent and consistent experience, so I guess we are longing for these perishable perfect moments”. DaddyBears admits that, despite the importance of lived experience, idealisation comes into play: “maybe I'm romanticising the idea of girlhood, but I guess within art you have the right to do that”.

The term “girlhood” has been thrown around as a marketing label, a reclamation of a lost experience, an accusation of escapism and infantilisation, an invite to consume, a tool of self-expression. As often happens when an idea enters the mainstream, it loses nuance to be easily packaged and consumed. Artworks like those of Girlhood Lore invite us to overcome these simplifications and, as Greta Futura Langianni points out, to “remember we’re not passive consumers of what we see, but we can choose the narrative we feel is truer to ourselves”.