Dressing Dykes: What is the Future for Lesbian Fashion?

Dressing Dykes has been a monthly column on the Dollhouse for a full year now, and we’re coming to the end. I’ve written about drag kings and sex wars, Vogue and Sappho, and even things a bit closer to our present day. Yes, this is my final column - but lesbian fashion, and its history, is far from over. I want to take a moment to think about what lesbian fashion and queer fashion in general means for a steadily approaching future. In years gone by, queer people have had to hide themselves, their clothes being either visible protests or coded messages, but these days more of us are out and open than ever before. But what’s the meaning of the closet when it’s only inhabited by our queer garments, rather than ourselves?

Some lesbian and queer women’s fashions from the past continue to exist today. We hold onto them, a link to our history that confirms that we’ve been around for a while. Think about dungarees - or overalls, if you’re in the US - and how they’re a quintessential lesbian style stereotype. There’s a reason for this; they were worn by female workers in World War Two, which for many women was the first taste of trousered freedom, and continued to be worn by women in blue-collar jobs throughout the twentieth century. These jobs, partly because of their uniforms or necessary practical clothing, often attracted working-class butch lesbians.

When lesbian feminism came about in the 1970s and 80s, and with it a celebration of androgynous, practical style, dungarees were championed yet again. Their lesbian legacy reigned for decades, and in 2004 an article called ‘My Lesbian Life’, written by Melissa Hobbes for The Sunday Times, she described how she “was devastated” to realise she was a lesbian “because I thought I would have to cut my hair off and wear dungarees.” Good, bad, or ugly, dungarees had a lesbian association. Though universally popular today, thanks to brands like Lucy & Yak, dungarees remain a favourite in the lesbian and wider queer community. Stroll through Brighton’s North Laine, for example, and this is made loud and clear.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

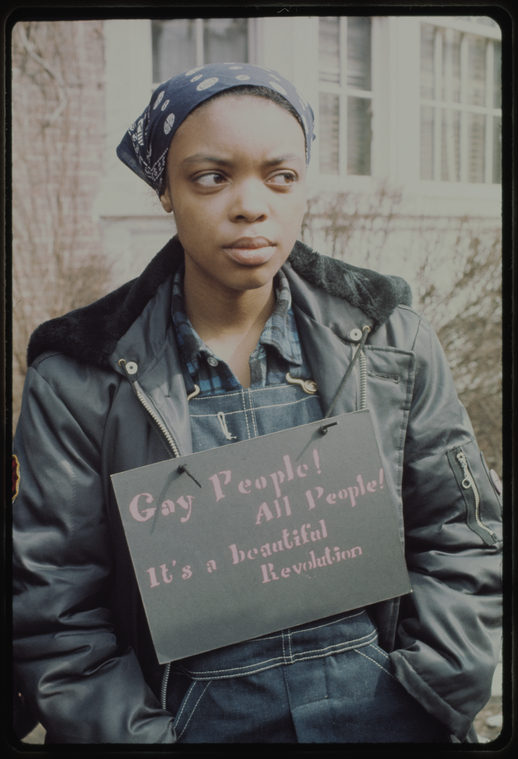

“GAY PEOPLE! ALL PEOPLE! IT’S A BEAUTIFUL REVOLUTION,” March on Albany for Gay Liberation, Albany, New York, 14 March 1971. Photo by Diana Davies. New York Public Library.

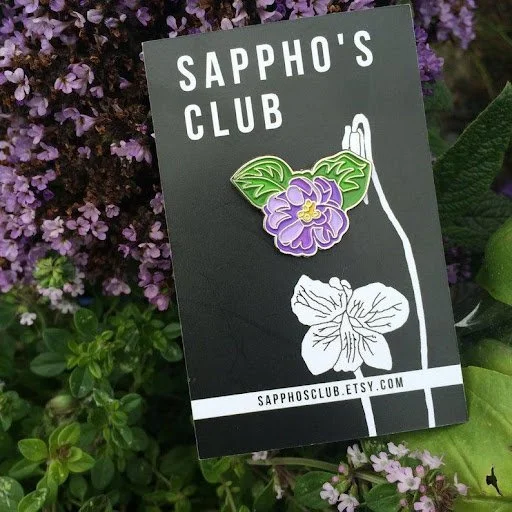

Other lesbian style signals are being purposefully reclaimed because they have a history. On my own TikTok page, whenever I’ve posted about the lesbian history of pinky rings, violets, or carabiners, my comment section is full to the brim of enthusiastic teens demanding we bring them back. After all, it’s not like it’s hard to wear a pinky ring or buy a violet pin on Etsy… and with platforms like TikTok showing information to a tailored audience around the world, the message gets out pretty quickly.

Queer style these days is diverse, but still somehow recognisable. Memes float around the internet about gay people dressing in particular ways to go to brunch, attached to images of the Muppets or characters from Matilda. These depictions of queer style are diverse, and yet they strike a chord. Our fashions have evolved, but they’re still legible to one another, whether through stylistic codes or the unconscious choices made when constructing an outfit in the morning. We see ourselves reflected in online space, then when we see each other on the street we somehow know it. Sure, sometimes we might be wrong. Straight people have been known to wear dungarees, or Doc Martens, or dress like the mum or Miss Honey from Matilda; that doesn’t mean that these styles aren’t still queer.

Despite the growing universality of queer-coded style, there’s still demand for specific lesbian fashion codes and, more than that, for them to be new. These are codes born out of the internet age, separate to the winding fashion histories that have come before. Think-pieces and deep-dives have already been written about the recent trend for lesbian earrings, but here’s a summary: lesbians and other queer people online started making unconventional objects into earrings - think paperclips, cardboard packaging, tiny plastic animals and, more recently, negative covid tests. By merit of those most involved in the trend being lesbians, these became known as #lesbianearrings. One TikToker, interviewed for online platform Them, said that “It’s about being comfortable expressing femininity in a queer-coded way, instead of what you’d think of as ‘traditional femininity.’”

It’s because of the internet that these earrings became lesbian-coded. It’s because of the way that we interact with each other online that a new lesbian style staple was born. Communities around the world know about #lesbianearrings - perhaps not every queer person, or even young queer person, but more than ever knew about monocles or pinky rings in the 1920s, for sure. In fashion historian Katrina Rolley’s 1995 research about lesbian fashion between the world wars, two of her interviewees said that pinky rings were “specific lesbian symbols”, but another, Ceri, said there was “nothing for lesbians. Not till well after the war.” However, Ceri also said that “if you could manage a monocle, that was very popular”, which implies that the lesbian community was fractured and divided by factors like class, age and location. These fractures are definitely not invisible today, but there are more crossovers within the community than there ever have been before. Perhaps this is the future of lesbian fashion: diverse, but recognisable. Different, but united.

Violet pin inspired by queer women wearing violets in the 1920s, who in turn were inspired by the poetry of Sappho. Sold by Sappho’s Club on Etsy.

Fashion as a way to signal sexuality might seem outdated in a landscape of online dating profiles and social media bios. When we form so many of our communities and friendships online, where information is at our fingertips, it might be that style codes are redundant. I don’t think this is the case, though. Clothes will always have a unique place in how we relate to one another because they’re how we present ourselves, the barrier between our personal, private selves and the outside world. Whether we share our outfits online or by walking down the street, they remain that barrier, that non-verbal communication of who we are. A lesbian fashion future, to me, is one that is honest and bold. It is one where our closets are just for our clothes.

Words: Ellie Medhurst