Dressing Dykes: The Miraculous Masculinity of Gladys Bentley

Make it stand out

As an interlude between part one and two of drag king history, I’d like to introduce you to someone hailed as a founding influence on drag kinging as we know it: famous male impersonator of the 1920s, Gladys Bentley.

Gladys Bentley: blues singer, tuxedo wearer and lady lover. In the words of Saidiya Hartman in her fantastic book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, “Bentley was abundant flesh, art in motion.” In the words of Bentley herself, from 1952 when she had left the stage and all that came with it, “a big, successful star – and sad, lonely person.” There are many ways to read Bentley’s life, and one of them is through clothing. The clothes she wore not only had an impact when they were first paraded around the streets of New York City, but have continually influenced queer culture and fashion.

Gladys Bentley was born in 1907 and lived until 1960. She ran away from her home in Philadelphia at 16, fleeing to a new life in New York City. When she reached New York, she quickly auditioned with a Broadway agent, and recorded eight record sides before ever having been on stage – but the stage was where Bentley’s career took off. She got her first job as a pianist at a club after the male pianist there suddenly left, and she was an immediate hit. The name Gladys Bentley, as well as her short-term stage name, Barbara “Bobbie” Minton, became ingrained within New York City’s nightlife. She was well-known as a “bulldagger” and had female lovers, left right and center. She was married in a civil union to another woman, speculated to have been a white woman. She crossed boundary lines of race, class, sexuality and gender.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

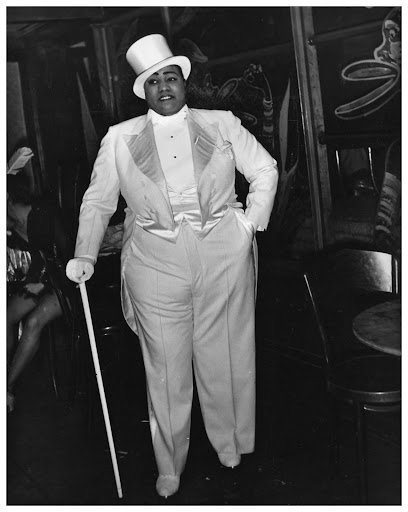

Gladys Bentley, c. 1940. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Bentley’s existence was a fluid one in many ways, including gender. Because of this, I’m going to refer to Bentley with a mixture of “she” and “they” pronouns in order to reflect the way that they understood themselves at different points throughout their life. This is a choice that’s been discussed already by many other writers; though I follow in their footsteps, I’m situating Bentley today within a wider history of lesbian fashion. Bentley and the clothes that they wore are part of lesbian fashion history, but they are also part of so much more. Bentley was primarily a musician, but it is their clothing that has preserved their image for a century.

At the peak of Bentley’s career, their typical outfit consisted of a tuxedo, complete with top hat and cane. Bentley described their style at this period when they wrote their autobiographical article from 1952, ‘I Am Woman Again’: “From Harlem I went to Park Avenue. There I appeared in tailor-made clothes, top hat and tails, with a cane to match each costume, stiff-bosomed shirt, wing collar tie and matching shoes. I had two black outfits, one maroon and a tan, grey and white.” Not just anyone could wear outfits like this. The fact that Bentley was so different was their strength – at least for a time. They were seen as a masculine woman, a male impersonator and an unabashed lesbian. They couldn’t be avoided, dressed as they were in their glossy, expensive costumes and equally fantastic streetwear. They were Black and fat and so talented, so captivating, that they left their audiences begging for more.

Bentley knew that it was difference, as well as talent, that cemented their audiences, knew that although “I had violated the accepted code of morals that our world observes […] the world has tramped to the doors of the places where I have performed.” Their clothing, combined with their talent, was Bentley’s unique selling point. However, Bentley existed past the walls of the club: they walked the streets of Harlem in men’s clothing with pretty women on their arms. They visited the opera with their “wife”, while “wearing a full dress suit.” They inspired young lesbians, other gender non-conforming women and modernist female husbands. They could do all this, at least for a time, because their fame made them near-untouchable.

It didn’t last. Bentley became too well-known, the United States too scared of Black and queer deviance. In 1940, Bentley was no longer allowed to wear trousers for her act at a bar she frequently performed in, Joaquin El Rancho. It was, as described by scholar Regina Jones, a “perceived fashion transgression.” The fashion of Gladys Bentley was what signposted her for deviance – for homosexuality – more than any of her private actions, or even her suggestive lyrics. Her proud, loud relationships with women were picked up on, and as the US edged towards McCarthyism and the mid-century, The U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities investigated Bentley. Her difference was becoming not so desirable as it had once been.

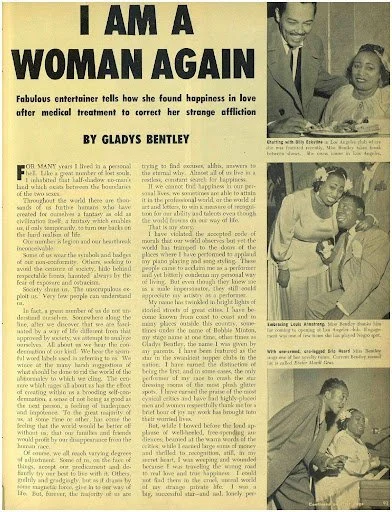

Gladys Bentley, ‘I Am A Woman Again,’ Ebony Magazine,’ Aug. 1952. JD Doyle Archives, via queermusichistory.com.

The big mystery of Bentley’s life is how she ended her career married to a man, wearing women’s clothing and declaring in the 1952 edition of Ebony magazine that “I Am A Woman Again.” At least, without social context this appears to be a mystery. When you know that Bentley had been finding it increasingly difficult to work due to censorship and growing concern about her morality, it makes sense as the only option to preserve her career. I do not believe for a second that Bentley became “Woman Again” because she wanted to, but rather because she had to.

In the 50s, for the Ebony feature, Bentley is pictured in long dresses, with shoulder-length curled hair adorned with flowers and a full face of make-up. In many images, she’s surrounded by men, which serves to make the distinction between masculine clothing and the clothes on her body even clearer. In her own account, she describes how a doctor had prescribed her with female hormones, which would “affect me greatly.” Her difference, her love of women, her fashion – these all had to go. They had to be eradicated.

In Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, she considers Bentley as having “nothing feminine about him; it was more than glamour drag, more than a woman outfitted as a man, as several of his wives, both white and coloured, could attest.” If Bentley was not in drag when they performed, nor when they traversed New York throughout the 20s, 30s and 40s, they were in drag when they appeared in the pages of Ebony, ready to convince a world that was against them that they were something acceptable, harmless and cured. Gladys Bentley’s clothing shaped her image throughout her life, but an image is a fragile thing. It can be changed at the literal drop of a hat.

If becoming a woman – and the association here is a heterosexual woman – was the way to survive, then that’s what Bentley did. But “becoming” only reaffirms what Bentley knew throughout her life: that “becoming” can be undone, and the way that we are known is fluid.

What remains is Bentley’s influence. In Wayward Lives, Hartman also writes about Mabel Hampton, a dancer during the Harlem Renaissance and one of the co-founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archives: “Mabel learned a lot from [Bentley] about claiming a space in a world that granted you none.” Bentley represented the power of the presence of a Black bulldagger. Bentley represented a link in a chain of drag kings and male impersonation. Bentley represented how our clothing can shape our place in the world and that, though sometimes we dress to quieten ourselves, the times that we were loud live on.

Gladys Bentley, c. 1925-1939. JD Doyle Photographs, JD Doyle Archives.

Words: Ellie Medhurst

This article has been adapted from an earlier version on dressingdykes.com