Dressing Dykes: Madge, Dody and lesbian Vogue

These days, we might think that Vogue magazine is the queerest it’s ever been. When could it have been more so, right? There are more out LGBTQ+ celebrities than ever, and our style is often celebrated where once it was scorned. Last Summer, Vogue even ran a photo story about New York City’s Dyke March. But what if I told you that lesbians had made themselves a home at Vogue magazine a hundred years ago?

It’s 1922, and British Vogue has been running for 6 years. It launched in 1916, partially in a bid to expand the Condé Nast company and partially to keep Vogue running in the UK during the First World War - previously, the American edition had been shipped over and sold instead. The general consensus is that the first editor of the magazine was a woman named Elspeth Champcommunal, though accounts vary. It’s definite, though, that by 1922 a new editor was at the masthead: Dorothy Todd. Not long after Dorothy’s - or Dody’s - appointment as editor, another woman rose to prominence at the magazine. This was Madge Garland, Dody’s lover and British Vogue's fashion editor.

A contemporary of both women, Rebecca West, reflected on the pair with an evocative description in 1972:

“Dorothy Todd was a fat little woman, full of energy, full of genius, I should say. Good editors are rarer than good writers, and she was a great editor, and Madge Garland was her equal. She was a slender and lovely young woman, who could have been a model […]. Together these women changed Vogue from just another fashion paper to being the best of fashion papers.”

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Dorothy Todd (right) and Madge Garland (left), c. 1930. Photography Madge Garland Archive, Royal College of Art Special Collections. Accessed via vogue.co.uk

Both women clearly made an impression - not just on those who met them, but on the magazine they worked at. This is not just lesbian fashion in history, but lesbians shaping fashion history. During the 1920s, British Vogue was, perhaps, something akin to an queer utopia of art and fashion… at least for the middle- to upper-classes who could afford the magazine. In Nina-Sophia Miralles’ Glossy: the inside story of Vogue she writes that “for a short while it seemed everybody involved with Vogue was part of a sexual subculture.” Though this was a team effort, built up by the likes of queer contributors like Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, it could not have happened without Dorothy Todd at the helm, hiring who she wanted and featuring what she pleased. “To look at Brogue [British Vogue] in the early twenties” summarises Miralles, “is to see through the gaze of a forceful, adept and visionary editor, one who was not afraid to cross lines and push boundaries.”

The context of 1920s fashion was already boundary-pushing, but Madge and Dorothy celebrated these trends and made them respectable in the fashion world. “Modernism” was the buzzword and women’s fashions were changing drastically; there were short haircuts, shortening skirts, the occasional trouser at a sporting event and high collars on structured shirts. These trends appeared time and time again among British Vogue’s pages, in cartoons and fashion plates. Styles that were mocked elsewhere were labelled as fashion in Vogue. This, undoubtedly, had a lasting effect on women’s fashion… and, I think, the way that we dress today.

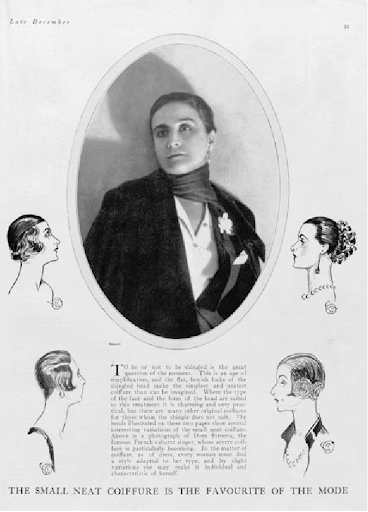

Photograph by Manuel in British Vogue, December 1923. Via Christopher Reed, ‘Design for (Queer) Living’, 2006.

Both Dody and Madge’s biographies are expansive, though Dody’s fizzles out much faster than her lover’s. Madge Garland had been born Madge McHarg, a fashionable blonde Australian who landed a job as an errand-runner at British Vogue and worked her way up the metaphorical ladder. She survived for a time on eggs and coffee, and only married her husband, Ewart Garland, for financial support. She didn’t take her husband’s name until the famous lesbian writer Gertrude Stein convinced her that Garland sounded more appealing than McHarg. Her position as fashion editor directly correlated to her relationship with Dorothy, though neither of them minded the favouritism - Madge was good at her job, after all.

Dody cared about art and literature as much if not more than fashion itself, and adjusted the focus of British Vogue accordingly. She had a daughter who she treated as her niece, whose father is unknown - it’s possible that Dody fell pregnant after being sexually abused. This illegitimate daughter as well as Dody’s loud lesbianism cast shadows over her reputation. Though her career thrived in the early 1920s, it burnt out quickly, and in 1926 both Dody and Madge were fired from British Vogue. They had made the magazine too “bohemian”. Their lesbian influence had been too strong.

It’s not so much the fashions worn by Madge and Dody themselves that are important to (lesbian) fashion history, but the fashions that their lesbian selves, alongside their queer friends and colleagues, brought to the pages of British Vogue. Between the years 1922-1926, the magazine normalised queerness in mainstream fashion – even if that queerness, as the saying goes, “dared not speak its name”. For a while, it flew under the radar, but it made its mark nonetheless. When Dody was fired, the work that she had started could not be wiped away. Dody tried to find her way back into the fashion world, but never held any kind of editorial position again. Madge, on the other hand, wrote for other publications until 1933, when she returned to the position of fashion editor at British Vogue until 1940. The relationship between the couple eventually crumbled, possibly under the stress.

“It’s not so much the fashions worn by Madge and Dody themselves that are important to (lesbian) fashion history, but the fashions that their lesbian selves, alongside their queer friends and colleagues.”

Dorothy Todd’s fashion history legacy is indisputable, despite only being in action for four years. Madge Garland’s legacy contrasts with it, though, because she remained in the fashion world. For the rest of her life, she continued to leave her mark on fashion in Britain. After Vogue and after WWII, she helped found the first British degree programme in fashion design at the Royal College of Art. Many years later, when she retired from RCA, she wrote books about fashion history – literally building the fashion history canon. To quote April Callahan and Cassidy Zachary from their podcast Dressed: The History of Fashion, she “emerged as a fashion authority.”

Despite all of this, she is little known. Dorothy Todd, despite her innovative take on Vogue and the way that she highlighted leading modernist artists and writers, faded to obscurity. Their names may not be shouted from the rooftops, but that does not mean that their work does not have a legacy. Madge Garland and Dorothy Todd are not lesbian outliers within the history of fashion. We have to keep finding lesbian fashion history and celebrating it. Whether through the lens of lesbian history, queer history, fashion history or any history at all, the role of lesbians and their clothing deserves to take up space.

Words: Ellie Medhurst