Demystifying PCOS

TW: Discussion of mental health, eating disorders and weight.

Of all the transformative experiences that made up my year abroad in Spain, being diagnosed with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) during the strict coronavirus lockdown was by far the most surreal.

My mood became unpredictable; I'd snap at the smallest inconvenience. There were days where my depression got the better of me and I barely had the energy to brush my teeth. Painful patches of acne broke out over my face and back, and my lower stomach felt bloated and cramped. And if that wasn't bad enough, my period had gone AWOL.

This was nothing new, for as long as I can remember my menstrual cycle has been irregular. The doctors I’d seen over the years put it down to stress, anxiety or simply “being a teenager.” I was underweight for most of my late teens due to an eating disorder (that I’m still in the process of overcoming) and went over a year without having a period at all. At 22, I assumed dodgy menstruation, acne and excessive facial hair growth was another act of war with my own body and I blamed myself for it.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Still, the overwhelming uncertainty of the lockdown heightened my stresses. Convinced there was something wrong with me, I must have taken around five pregnancy tests in the space of a week. When they all came back negative, I did the ill-advised task of googling my symptoms and booked a doctor’s appointment.

My GP reassured me that I was not suffering from a phantom pregnancy and booked me blood tests and a gynaecology appointment. I’d never been to a gynaecologist before, and while the prospect gave me major Carrie Bradshaw visiting her Manhattan OBGYN energy, in reality, there was nothing glamorous about being probed by a plastic ultrasound camera. Especially after the grand reveal that my ovaries were as lumpy as the surface of the moon.

These little lumps, or to use their proper scientific name, ovarian follicles, may prevent the release of eggs if they are undeveloped – as mine were – leading to irregular, or no, menstruation. The numerous undeveloped follicles that grow across the ovaries – the ‘poly’ in ‘polycystic’ – affect the regular balance of sex hormones including estrogen and androgen, hormones which directly monitor and control the menstrual cycle. However, irregular sex hormones aren’t the only problem.

PCOS is known as a “heterogeneous endocrine disorder”, a whole-body hormone imbalance – meaning that when one type of hormone stops working regularly, the entire hormonal system is impacted.

This domino effect leads to some typical symptoms associated with PCOS: including resistance to the hormone insulin – responsible for maintaining stable blood-sugar levels – which causes weight fluctuations and increased levels of testosterone, excessive facial and body hair growth known as hirsutism, and perhaps most critically, a direct impact on hormones that regulate mood.

Just as there is no singular determining cause of PCOS, there is no standard treatment. I was advised to take the contraceptive pill to regulate my periods and reduce the acne, but there was no further discussion on how to cope with my unstable mental health. I wanted answers – but the more I researched, the more questions I had.

The majority of resources I found were geared towards women looking to conceive, as PCOS can negatively affect fertility, but I struggled to find any substantial information on the lived experience of PCOS. It was only through sharing my own experience and opening a conversation about the nitty-gritty - the abdominal bloating, the pregnancy scares, the hairy nipples – that PCOS started to make sense.

“I honestly couldn’t breathe”, Emily, a PCOS and endometriosis sufferer told me, “It was like a knife bursting into my whole body, including my legs and lungs. In a year I saw a ridiculous number of doctors, over fifteen. It was only this year that they finally discovered it was PCOS. It hurts doubly because you can feel something is wrong inside you but you are unable to stick a word on it.”

Endometriosis is a similar reproductive organ related illness, where excess tissue grows on parts of the fallopian tubes and ovaries and can cause extreme pain. Like PCOS, the causes and effects of endometriosis are yet to be fully understood, and it can take many years to reach a conclusive diagnosis.

“Repeated blood tests told the doctors there was something wrong, as I have abnormally high testosterone and reduced estrogen,” Jess, a fellow PCOS sufferer told me, “But was told that was something that would subside and ‘sort itself out as I got older’. It took years for a doctor to believe me and send me for a scan which led to the PCOS diagnosis. To this day I still suffer with hormonal cystic acne, mood swings and hirsutism (excessive hair growth) which really affects my mental health and confidence. I’ve been offered no guidance on management or treatment.”

Jess and Emily both experienced the negative impact of hirsutism on their body confidence and self-image, something I have personally struggled to reconcile with as a keen advocate of destigmatising female facial and body hair. Embracing your peach fuzz, monobrow or cute moustache fluff is all well and good when its your decision, but the intensity of hirsutism hair growth limits this choice, making it very inconvenient – and time consuming – if you prefer to be hairless.

Although I have made the decision to not shave, I continue to feel self-conscious whenever someone – usually my very traditionally gender conforming mum – comments or draws attention to the hairs around my neck and chin. I can’t help but feel a pang of envy whenever I see a “body confidence” post on Instagram of someone with neat, tidy armpit hair, or almost invisible leg hair.

It strikes me – as a cis woman – that there’s still a “right” and “wrong” type of hairy to be, despite all the progress that has been made to free body hair from the toxic rhetoric of gender binarism. We still have a way to go.

Aside from unruly body hair, PCOS can also cause fluctuations in weight – something that set my own mental health off kilter. My history of disordered eating made the changes I noticed in my body terrifying to address, especially as they seemed entirely out of my control.

Research presented at the 2016 American Society for Reproductive Medicine conference showed that women with PCOS were six times more likely to experience some form of eating disorder. Mental Heal UK have listed hormonal imbalances – including insulin-resistant PCOS – amongst common causes in the development of disordered eating. It is worth reiterating that insulin resistance impacts blood sugar levels, and the body’s failure to absorb glucose has been cited by eating disorder specialist Amy Enright as a particular trigger for binge eating.

It doesn’t help that connection between PCOS and insulin resistance is often articulated in the problematic language of diet culture and thinly veiled fatphobia – the take home message – it's your fault. When PCOS sufferer Liberty was tested for the condition, she was told that her ‘results wouldn't be clear’ as she was plus sized, and was advised by her GP to lose weight. The societal stigma around fat often finds its way into medical discourse, with weight loss as a common “recommendation” for people with PCOS, alongside numerous diets that claim to “heal” the condition. Nonetheless, the idea that weight and PCOS are inextricably linked is not medically conclusive – as Liberty told me, ‘…weight has nothing to do with it [PCOS] and never has.’

In attempting to unravel the mystery of PCOS, speculations around body weight have complicated the conversation further – collapsing negative interpretations of fat with poor health, paying very little regard to the genuine credibility of these claims. It can sometimes feel like the more resources you encounter, the harder it becomes to navigate the tangled web of PCOS – often leading to feelings of confusion and anxiety.

Feeling out of control, at odds with your own body, seems to be the common denominator of the PCOS experience. For Liberty, ‘the condition and its connotations have skyrocketed my anxiety and depression.’

Similarly, Melissa, a member of the Facebook support group All About Ovaries, reached out to explain the intricacies of her experience living with PCOS:

‘I feel like my emotions are very up and down all the time, I have about one good steady week where I feel good and confident, then it’s like my mood switches and I’m very low. I struggle with my mental health anyway, but this almost feels like it’s out of my control, and I definitely feel like it’s caused by my hormones as it happens in cycle.’

Melissa also expressed her concerns around the knowledge that PCOS may affect her ability to conceive, a bleak outlook even for someone who hasn´t considered starting a family just yet – having the choice limited before you can make it can feel overwhelming. It is this sense of uncertainty that continues to define PCOS, making learning – and listening – to the experiences and thoughts of those who live with this condition all the more crucial.

Beyond support groups run by those who suffer with PCOS and similar ovarian conditions, there is limited support and no general awareness of the multifaceted nature of PCOS – it almost feels like an exclusive club, you have to have it to be in on the PCOS experience. Megan Stewart of the PCOS Awareness Association has found that over half of women with PCOS actually go undiagnosed – given that so many of the symptoms are shared with other conditions.

When I´d seen my doctor about irregular periods in the past I was always assured that it was ‘just stress’ or weight related – and a number of PCOS sufferers I spoke to in the process of writing this article experienced a frustratingly prolonged period of not knowing exactly what was wrong before their diagnosis. Even then, no one really knows what PCOS is, what causes PCOS, or why it affects people in such a broad variety of ways. Sometimes its better to leave the Wikipedia page and turn to those around you.

Letting friends and family in on how you’re feeling - your moods, your concerns - is an important way to extend the discussion. While branching out emotionally can be difficult, I really believe being vocal, and educating those around me on what living with PCOS means for me personally, not only helps me organise my messy feelings into clear patterns – but helps extend an awareness of PCOS more generally.

Community is important, now more so than ever, and dedicating specific times and dates to catch up with friends on FaceTime, going for a countryside walk, or even baking cookies with your flatmates can help you stay connected. As PCOS hinges a great deal on mental health, it may be useful to see this as your priority in coexisting with badly behaved hormones – and I´ve personally noticed an improvement in my own relationship with my body as a result of putting my mental wellbeing first.

Personally, I have found reading blog posts and listening to podcasts from people with similar experiences – including the wonderfully inspirational and funny Not Plant Based website – as an important means of reminding myself that I am not alone in living with PCOS.

There is no one solution to the problem of PCOS.

Rather than focusing on trying to solve the mystery, it is worth focusing on yourself, tuning into your mind and body. Just as most PCOS symptoms are personalised, the trick of dealing with PCOS may, quite literally, be entirely up to your own experience of the condition.

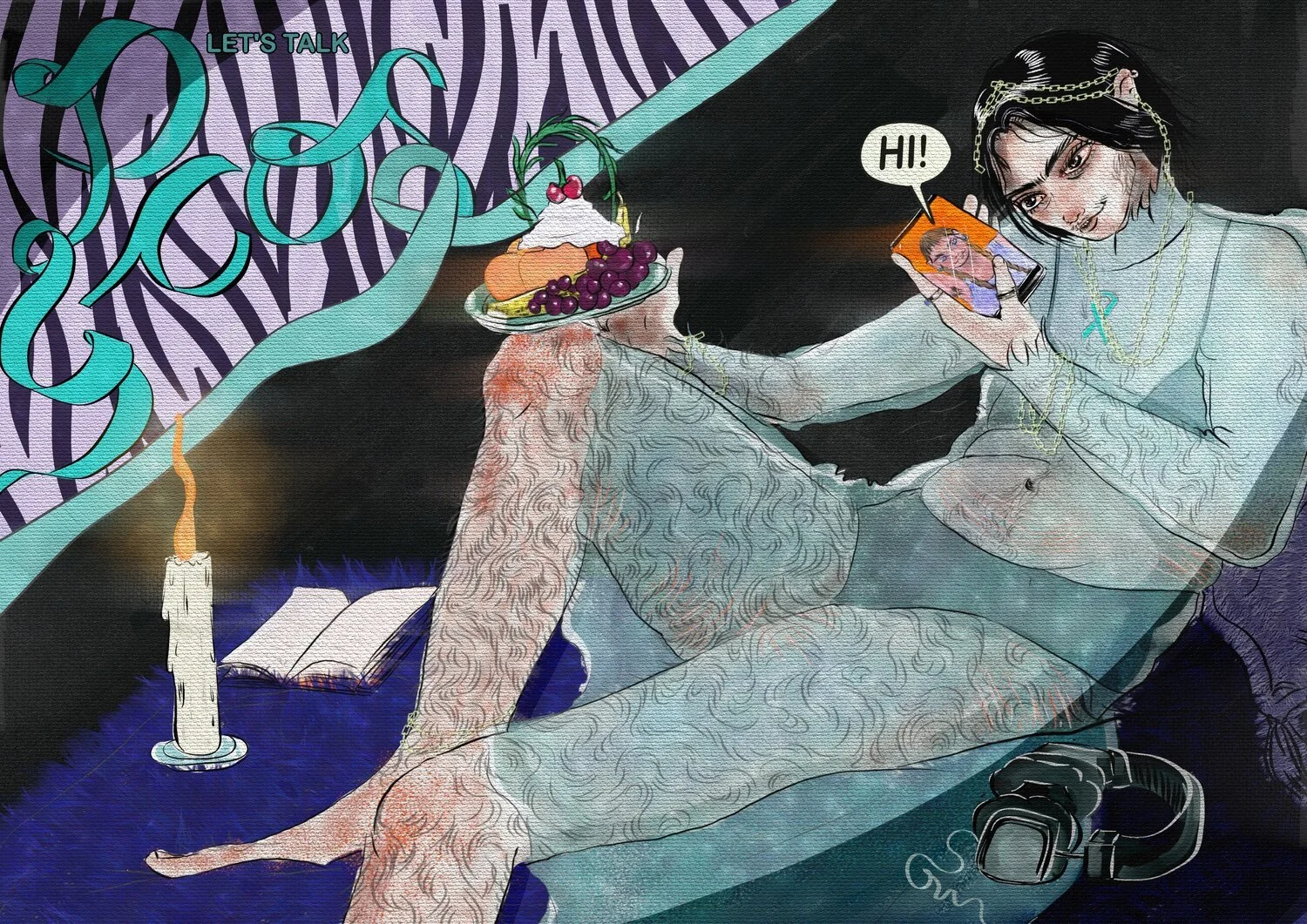

Words: Carmen Walker-Vazquez | Illustration: Chiara Girimonti