Dedicated to the Press: Extra! Extra! Have You Read About Angela Davis & Kate Millett?

Make it stand out

This column offers an original contribution to the existing historiography on social movements and the mass media by investigating radical American feminists who became celebrities in the 1970s. Mainstream celebrity feminism, as demonstrated by Nathalie Weidhase, is characterised by ‘Whiteness.’ Political writer Todd Gitlin argued that the mass media looked for movement leaders who were both ‘flamboyant’ and ‘reformist’ in their politics. Radical feminist Kate Millett and Communist Party USA (CPUSA) member Angela Davis disrupted these conventions of celebrity yet still reached celebrity status, becoming the face of their respective movements at this time. This is why they are significant to study.

To begin my column this essay investigates how mainstream newspapers and commercial magazines utilised sexist feminist stereotypes to depict Millett and how racist stereotypes were used to describe Davis. In the end, these representations and dilutions defined the WLM, feminism and the BPP, impacting the public debate about feminism and Black liberation at this time.

‘I can’t be Kate Millett anymore. It’s an object, a thing. A joke at cocktail parties. It’s no one.’ In her autobiography, Millett expressed that she could no longer be connected to her name. Her name is no longer her own, it has become ‘an object’ to be used, seen and touched. She cannot be ‘Kate Millett’ because ‘Kate Millett’ has no agency. When Millett released her book Sexual Politics - a book based on her PhD dissertation, that argues that patriarchy is a political system that relies on the submission of women, and that what goes unexamined in society but is still institutionalised is the 'birthright privilege’ that authorises men to rule women’- it was a significant month for the Women Liberation Movement (WLM). In August 1970, the new WLM held their first mass protests known as the Strike for Equality. Additionally, August 1970 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, which mainly provided White women with the right to vote in the United States. This timing aided the sales of Sexual Politics and influenced mainstream newspapers and commercial magazines to label Millett the leader of the WLM.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Likewise, Davis wrote about the lack of agency she had over her image in her 1994 essay ‘Afro Images: Politics, Fashion and Nostalgia.’ Davis explained that one woman introduced her to her brother, but the woman’s brother did not recognise her, ‘’You don’t know who Angela Davis is?! You should be ashamed.’ Suddenly a flicker of recognition flashed across his face. ‘’Oh,’’ he said, ‘’Angela Davis - the Afro.’’ Twenty-four years after being put on the FBI’s Most Wanted List, Davis is remembered because of her hair, rather than her politics. She is marked by how mainstream newspapers and commercial magazines depicted her; Davis’s politics of liberation was simplistically reduced to a ‘politics of fashion.’

“It can be argued that Time distorted the image of the WLM because the complete accuracy of what they were reporting did not matter, as long as it looked like they were providing women with space in their publication.”

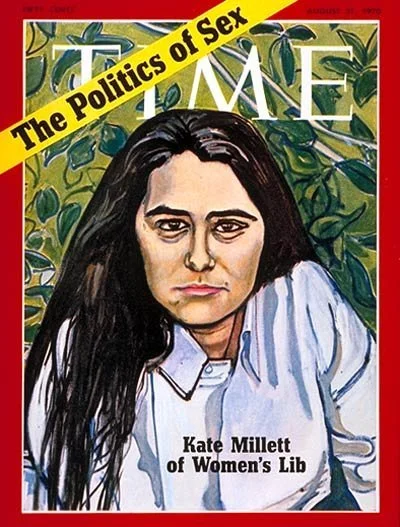

On August 31st 1970, Time released their women's liberation issue. On the cover was a painting of Millett by artist Alice Neel. Millett explained in her autobiography Flying that she was asked to pose for the cover but refused. She advised them to put ‘no one woman but crowds of them’ on the cover.’ Instead of respecting Millett’s request, Neel used photographs of Millett to paint her likeness. This situation emphasises why Millett declared that ‘Kate Millett’ is ‘no one’, especially in the eyes of the media. It demonstrates that publications like Time believed they had ownership over Millett’s image.

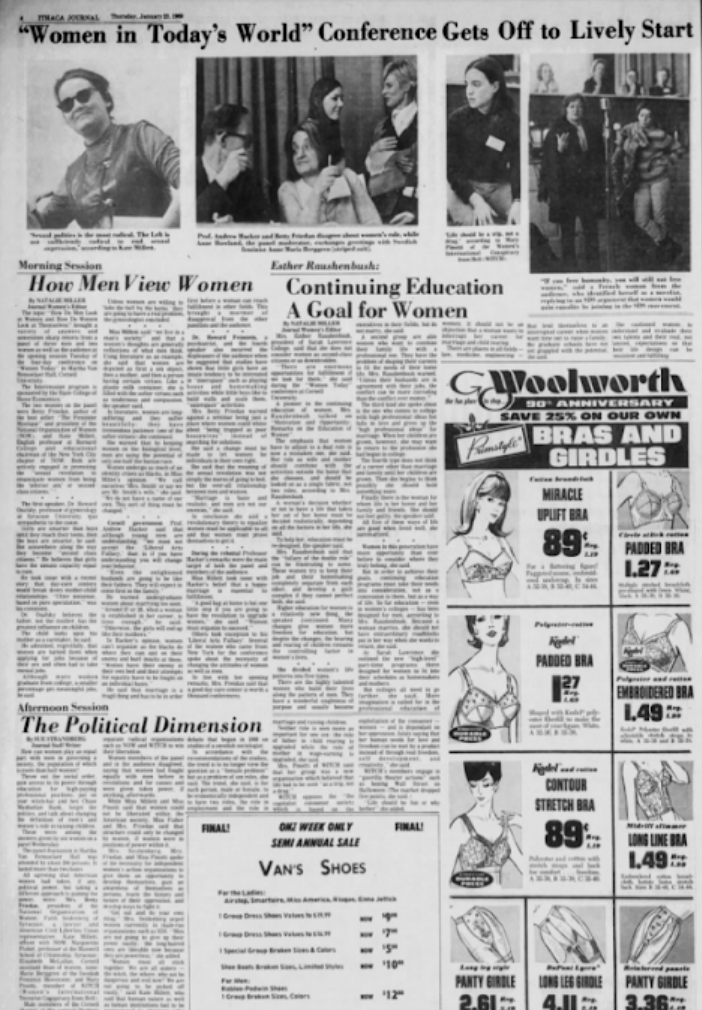

On this cover, Millett is depicted as stern and assertive. Millett's facial expression translates this, she is staring straight at the reader with a resilient and solemn expression; Millett is sitting forward aggressively as if she is prepared to fight. Being stern, or aggressive are qualities often associated with masculinity. On this cover, Time tried to represent Millett as a masculine woman, she is wearing an Oxford shirt, 'a style reminiscent of a middle-class American man.’ This is inconsistent with how Millett presented herself at this time. Between 1960 and 1969, it is difficult to find reports of Millett by mainstream publications, but she is present in local newspapers. The Ithaca Journal, a daily morning broadsheet newspaper published in Ithaca, New York, reported on a WLM conference Millett spoke at with other academics in 1969. A picture of Millett accompanies the article; she is smiling while she speaks to the audience and is dressed in a turtleneck, sunglasses and a stylish waistcoat. A conservative yet identifiably feminine outfit. As the educational chairman of the New York City chapter of National Organization for Women (NOW) and English professor, Millett is speaking at this conference as an educator. As a result, she dressed appropriately for the event. There is little similarity between the Millett painted by Neel and the Millett shown in the Ithaca Journal.

After crowning Millett ‘the high priestess of the WLM’, Time quickly began to question Millett’s intellectualism and the whole WLM. Time outed Millett as bisexual in an article titled ‘Women’s Lib: A Second Look’ in December 1970. A Time’s reporter secretly attended a Gay Liberation Front conference at Columbia University, where Millett's movement sister confronted her: ‘Are you a Lesbian?’, to which Millett said ‘Yes.’ Time wrote, ‘the disclosure is bound to discredit her as a spokeswoman for her cause, cast further doubt on her theories and reinforce the views of sceptics which routinely dismiss all liberationists as lesbians.’

Time concluded that Millett was bisexual because, at this time, she was married to a man. Millett’s bisexuality reaffirmed Time’s previous presentation of Millett as masculine. Millett’s sexuality gave credibility to the stereotype that the entire WLM were just a ‘bunch of lesbians.’ The discrediting of individuals because of their sexuality has a long history. In the 19th century, significant discoveries were being made through Sexology, the study of human sexual life. One of those discoveries by Richard von Krafft-Ebing in 1886 was that homosexuality had a specific link to mental illness, and the possible deterioration of the human race. Scientific homophobia is used to devalue the voices of all those who were not heterosexual, as a result, Millett lost her intellectual credibility.

By 1970, Time had shifted from their conservative political viewpoint as co-creator and editor Henry R. Luce left in 1964. However, this more centrist stance did not occur innocently. Three months before the women's liberation issue in August, one hundred and seven editorial workers from Time Incorporated filed a complaint of employment discrimination to the New York State Human Rights Division. The lawsuit was settled under the agreement that Time Incorporated would recruit women and promote them. The women's liberation issue was one example of the fulfilment of that promise. The lawsuit confirms that Time had a hidden agenda when it came to reporting the WLM. The coverage of the WLM was not enacted to highlight the movement but to protect Time Incorporated from further accusations of sexist discrimination.

This explains why there was a lack of care when it came to reporting about the WLM. Time named Millett the leader of the WLM, even though the movement mostly rejected single spokespersonship and reinforced the lazy stereotypes that all women’s liberationists were lesbians. It can be argued that Time distorted the image of the WLM because the complete accuracy of what they were reporting did not matter, as long as it looked like they were providing women with space in their publication. The circulation of Time by 1970 to the end of the 20th century was around four million. This was notably higher than its rivals; Newsweek who had a circulation of three million and U.S News & World Report who had a circulation of two point one million. It is clear that Time had considerable influence on the public, and their reporting did impact the public debates about feminism as the stereotypes they reinforced and created are still around today.

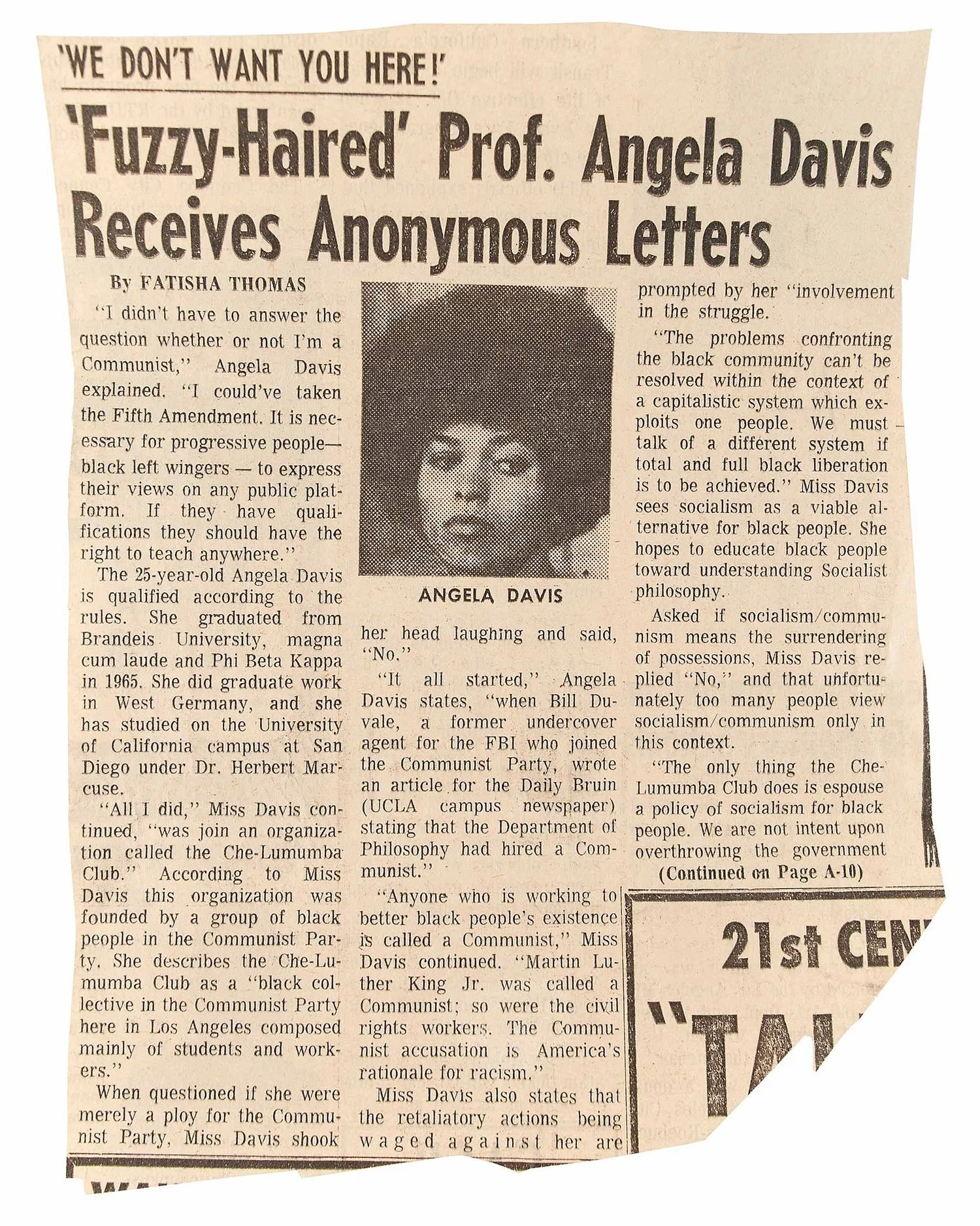

Similarly, mainstream media publications worked to discredit Davis’s intellectualism and activism. Davis did not become newsworthy until 1969, when she was fired from her assistant professor position at UCLA for being a member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Before that, there is little to no coverage of Davis. Once Davis made headlines, her coverage was racially charged. Shortly after Davis was fired from UCLA, the Los Angeles Times wrote an article about Davis titled ‘’We Don’t Want You Here!’: ‘Fuzzy-Haired’ Prof. Angela Davis Receives Anonymous Letters.’ This racialised and gendered headline provided the Board of Regents with justification for firing Davis. Afro-textured hair was seen as unprofessional, unattractive and unclean.

Historian Emma Dabriri noted in her book Don’t Touch My Hair that afro hair was used to justify the enslavement of Africans between the 16th and 19th century. Europeans believed Africans did not have hair on their head but wool, like animals or livestock. This comparison justified why Black people needed a master to control them. By describing Davis as the ‘Fuzzy-Hair’ professor, the Los Angeles Times puts into question Davis’s ability as a professional academic, as she was ‘unkempt’. The Los Angeles Times appeared to be rationalising the firing of Davis and distracting their readers from the fact she was discriminately fired. Furthermore, this focus on Davis’s hair by the Los Angeles Times was a direct attack on the natural hair movement that emerged during the 1960s. The ‘Black is Beautiful' movement was created to assure Black men and women that they did not have to subscribe to White eurocentric beauty standards to be beautiful. This racially charged comment was not just a throwaway comment about Davis, but a remark against the whole natural hair movement and Black liberation.

When comments were not being made about Davis’s hair, the focus was on her ‘redness’. The Los Angeles Times labelled her the ‘Admitted Red’ in 1969. Similarly, in 1969, Time called Davis 'Angela the Red.’ Red is the colour traditionally associated with communism; it was chosen to honour and symbolise the blood of workers who have died in the fight against capitalism. However, in the United States, the colour red and its relationship with communism represented terrorism and violence. Davis was only solely referred to as 'Black' when her name became connected to a crime. In 1970, J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI placed Davis on the FBI's Most Wanted List. Four people were killed using guns that belonged to Davis in an attempt to release the Soledad Brothers (George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo and John Clutchette). The Soledad Brothers were three Black inmates charged with murdering a White prison guard who killed three Black prisoners and Davis had previously shown strong support for these men. Mainstream media publications stopped referring to Davis as the ‘Red’ professor and only referred to her as ‘Black.’ This change can most explicitly be seen in the NYT’s reporting of Davis. As late as August 12th 1970, the NYT referred to Davis as a ‘Red Teacher’, a week later, on August 19th, they referred to Davis exclusively as a ‘Black militant.’

The combination of Communism and Blackness was doubly threatening to Americans. Communism was anti-American, but 'Blackness equated criminality and violence within the White American imagination.’ After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the founding of the CPUSA, there was a real fear of Black people and of communism threatening capitalism, and essentially threatening Whiteness. This fear was founded on the fact that the CPUSA ‘was at the forefront of denouncing anti-Black racism’, during the Great Depression. In the North, Black and White communists were fighting against displacement and demanding relief. In the South, Black and White workers battled against Jim Crow racism and capitalist repression. As a result of this union, government agents characterised Black protest as un-American, communist and a threat to the established order. In 1969, Hoover made the BPP the main target of the Counterintelligence Program's (COINTELPRO) unruly tactics. One of these tactics used the media to destroy the image of the Panthers. COINTELPRO ensured the BPP were depicted as hate-filled, anti-White terrorists who were randomly inciting violence.

Davis has typically fallen outside of the scholarship regarding the effective media assassination of the BPP because of her short time in the Party. While a lot of writing has highlighted the impact of anti-communist persecution on individuals, organisations and movements in the United States, very few studies have paid attention to its racial dimensions. Consequently, Davis’s Blackness, communist beliefs and association to the BPP ensured that the mainstream media publications invoked racist stereotypes about her, and defined her advocacy as violent without reason.

Overall, mainstream media publications used negative feminist stereotypes to depict Millett and used racist stereotypes to depict Davis. Both women had no control over how they were portrayed. Publications such as Time distorted the image of the WLM by naming Millett as leader. Furthermore, the FBI played a significant part in the gendered vilification of Davis by the mainstream media because of her connection to the BPP and communism. As a result, the coverage of Millett and Davis misrepresented the true image and goals of their respective movements. It is clear that these stereotypical depictions impacted the public debate about feminism, communism and Black liberation, because these stereotypes are still used today against women and Black people fighting for freedom.

Words: Halima Jibril | Illustrations: Julia Tabor