Daughters of Cain, Sharp Objects & How the Recession Gave Rise to the Southern Gothic

Words: Lydia Eliza Trail

Southern Gothic is an aesthetic which understands the world to be dying. It celebrates crucifixes, fading wallpaper, one-room schoolhouses and gauche, technicolour images of Jesus Christ. As a disclaimer - but you would be forgiven for thinking otherwise - Southern Gothic is definitely not Kim Kardashian’s 2018 editorial dressed in Amish cosplay. Instead, it’s true crime snapshots and a faded, dirty American flag. Southern Gothic is the sweat dripping from Robert Patterson’s brow in The Devil All the Time, the deranged sister of cottage-core, a Lisbon girl impaled on a white picket fence: it is the dialectic between the grotesque and American mythology.

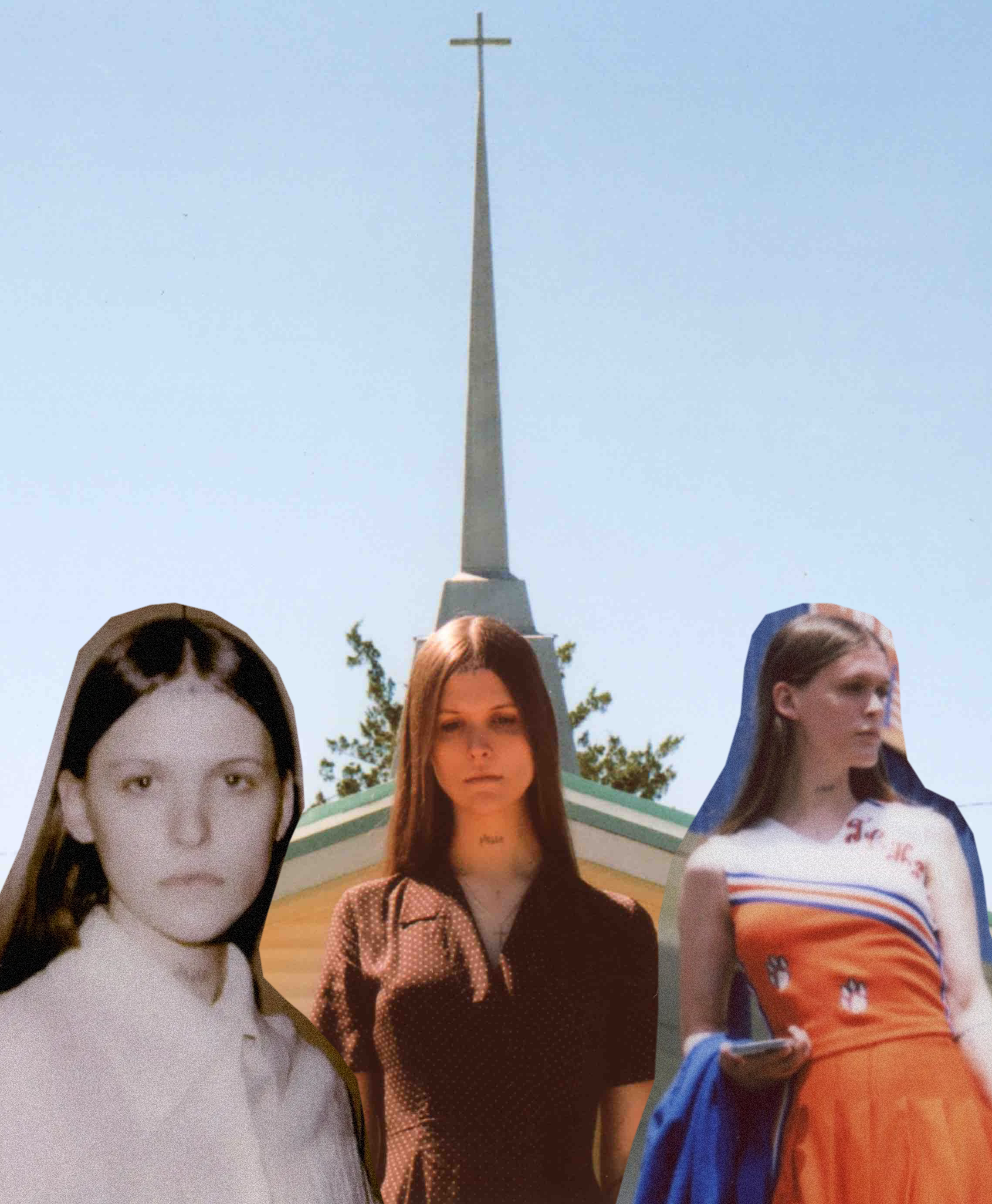

My first encounter with Southern Gothic was, as you might expect, on Tiktok. Much of its success appeared to originate in Hayden Anhedönia’s alter ego: Ethel Cain. Although not necessarily mainstream, #Ethelcaincore has garnered enough interest to induce dismay for those intent on gatekeeping Ethel Cain. There is no better summary, I think, of this aesthetic than Anhedönia’s description of her own fanbase, or ‘daughters of Cain’, as “Girls that fuck in dirt pits, girls that think mildew smells good, girls who know you’re supposed to smoke a lot of weed before listening to Preacher’s Daughter…”. A video on TikTok titled Very Specific Aesthetics pt.41 visualises Southern Gothic along similar lines. Tumblr-esque images abound; eerie churches inscribed with apocalyptic messages, a photographic recreation of the painting Christina’s World, and an editorial of Mia Goth wearing a nightgown in the forest. These are disparate elements, which, in typical TikTok fashion, appear to sanction the idea that being depressed and living in the middle of nowhere is enough to lay claim to an aesthetic.

Yet, in 2023, Southern Gothic is more than just a micro-trend. It’s deeply political. Crucially, there are theatrical visions of the genre found on TikTok, and then the reality of what it portrays. As we enter into a global recession, there’s significance in popular culture’s fetishisation of the South. Anhedönia, talking to The Face, describes the South as a corner of the States destined to crumble into oblivion, because that’s the way it was built. In this light, the region is an antidote to the false optimism and insipid lightness offered by neo-liberal identity. The red belt, in the US, is passè. It occupies a place of deep ambivalence in the American national imagination. Tara McPherson writes in Reconstructing Dixie: “the south today is as much a fiction, a story we tell and are told, as it is a fixed geographic space below the Mason-Dixon line”. Youtuber Natalie Wynn - aka ContraPoints - confirms this in her video essay ‘Opulence’, “Americana’s faded grandeur is easily mythologised into a Gothic romantic character”.

Southern Gothic appropriates the language of a much older tradition. European Gothic described a world caught in a ruinous state of violent decay sometime between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Norman invasion. The Gothic allegorised the world southerners faced at the end of the U.S. Civil War and again during the Great Depression, with authors like Tenessee Williams and William Faulkner. In A Street Car Named Desire, Blanche Dubois is a faded belle and a personification of the South: a morally dubious character who invokes the audiences’ sympathy and derision. For contemporary audiences, the Gothic South might be an abandoned church, a relic of a once vibrant community - embodying the melancholy of a society caught in a maelstrom of economic downturn and cultural acceleration.

Southern Gothic is un-accommodating to consumerism in a way that antecedent aesthetics or ‘cores’ on the internet are not. As we enter into a huge economic slump, the desire to build your own identity through Amazon shop-fronts on TikTok has been reviled. In Neo-Liberalism, large amounts of money are funnelled into convincing people that identity is about consumer choice. Still, it's much harder to marketise the abject.

“Southern Gothic may be alluded to through Pinterest boards, but its reality invokes generational trauma, religious fundamentalism and the macabre living just below the surface.”

Often, what this aesthetic conjures is not even material. It’s a lethargy - the sleepy air of the American South evoking a dark history through its stagnant present. Writer Stephanie LaCava describes the mass suicide of the Lisbon sisters, in Sofia Coppola’s 1999 The Virgin Suicides, as a “desperation to escape suburban gothic idolatry”. Southern Gothic may be alluded to through Pinterest boards, but its reality invokes generational trauma, religious fundamentalism and the macabre living just below the surface. The atmosphere is stifling, as Mother Cain warns us, the South is not for the weak hearted.

Conjuring beauty in things left behind is Southern Gothic’s modus operandi. What can’t be left behind is the history of Black life in the American South. In 2016, Beyonce released her seminal album Lemonade, heavily drawing on Julie Dash’s debut film Daughters of the Dust (1991). The film follows the female members of a Gullah-Geechee community off the coast of South-Carolina, at the turn of the 20th century. In both pieces of media, time is circular. Past, present and future run simultaneously. In the video for All Night, Beyonce sits on a typical southern veranda, reciting: “the past, the future, merge to meet us here”. Dash employs the southern landscape, rendered in hazy sepia tones by Arthur Jafa’s cinematography, as a backdrop for the multi-generational tales of the Gullah women. In breaking Hollywood’s expectation of Black cinema as violent, urban and gritty - Daughters of the Dust re-imaged the role of Black women in Southern history outside of popular media. Here, the southern gothic finds its most useful application; as a subversive tool, finding beauty in the unfashionable.

The TV show Sharp Objects is a modern Southern thriller based on the Gillian Flynn novel of the same name. A journalist, Camille, returns to her home in Wind Gap, Missouri, to investigate the murders of two young girls. Throughout the series, the protagonist is haunted by flashbacks to her youth. Between inscribing the words ‘sacred’ into her skin with a needle and thread, Camille ponders why graphic murders would occur in such a sleepy, conservative town. The viewer - the outlier - can’t imagine them happening anywhere else.

But Sharp Objects is just a part of a broader media genre exploring Southern Gothic. In True Detective, the Deep South becomes a stage-set for the occult. The cult True Detective follows embroils church leaders and Republican congressmen, cutting close enough to reality that it verges on the conspiratorial. This trend in Media toward horror-filled, Southern-located crime dramas reflects geopolitical anxiety about a marginalised, angry and disenfranchised Republican voter. As noted in James Pogue’s article for Vanity Fair on the dissident right - working-class southern voters have, ultimately, been abandoned by US politics. An en masse return to Southern Gothic by creatives as well as kids exploring aesthetics feels inevitable for anyone feeling abandoned or alone following a global pandemic, endless reports on corrupt governments and a culture pushing us further into isolation via individualism.