Culture Slut: On Gay Horror

The skies are dark, the shadows are long, the leaves are falling! The night is bitter, the stars have lost their glitter! The time is perfect for cooking some wholesome food, opening a bottle of wine, curling up on the sofa and delving into some seasonal horror. I look forward to this every year because horror is such a good space for fun queer representation and patriarchal subversion in cinema, from monstrous man-eating femme fatales to queer coded villains sacrificing frat boys to ancient demons, and so much more. Normally I immerse myself in the innate campness of supernatural horror - I really go buck-wild for some of the stranger Hammer Horror offerings from the 1960s and 70s in all their flamboyant occultism. Blood on Satan’s Claw and The Devil Rides Out stand out particularly in my mind. Both are part of what is now termed as folk horror, depicting satanic cults in rural settings with indulgent high priests, dramatic devilish incantations and the attempted ritual sacrifice of virgins and out-of-towners. What is more gay than summoning demons to destroy puritans and peasant-killing patriarchs? Overthrow greedy landlords taxing your farms! Bash the local baron pursuing your buxom blonde sister! Rise up against corrupt systems that run on the blood of the working class! In the words of Bruce LaBruce; The Revolution is my boyfriend!

This year is a little different for me. Instead of Satan worshipping in non-specific-ye-olde-times, I’ve been looking at modern productions that tell horror stories set at the beginning of AIDS crisis - so late 70s and early 80s. This train of thought was initially set into motion by the release of Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (terrible name, far too long), Ryan Murphy’s latest offering for Netflix, a series exploring gay serial killer and cannibal Jeffrey (you guessed it) Dahmer. Incidentally, I think cannibals are very chic and are long overdue a return to pop consciousness. Maybe as times grow increasingly hard in the cost of living crisis, it will give birth to more Sweeney Todd-esque cannibal horror stories. Or the current obsession of y2k fashion will lead us to a miniseries or film exploring the cannibal cafe message board and the subsequent German murder court case.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Dahmer is a return to Murphy’s more horror influenced fare and does a good job at bringing the unsettling atmosphere and unhinged killer to life. The real story of Dahmer is infamous: How he hunted guys down in Wisconsin, experimented with drilling holes in their skulls, eating their organs, picking up street hustlers, while also living in plain sight for so long. But I had always assumed he was an Ed Gein type, living in a farmhouse in the middle of nowhere, but here he is on television, inner city living, sharing a wall with a suspicious neighbour and everything. It makes for an excellent example of Gay Horror - a horror born of the isolation inflicted on queer people by a callous heteropatriarchy that wants nothing to do with them. Dahmer thrived because he was left alone. The same could be said of the AIDs crisis, it accelerated because governments did nothing.

“Gay Horror comes from our history, the violence we face and the crises inflicted on us by a malignant hegemony of capitalist conservatives.”

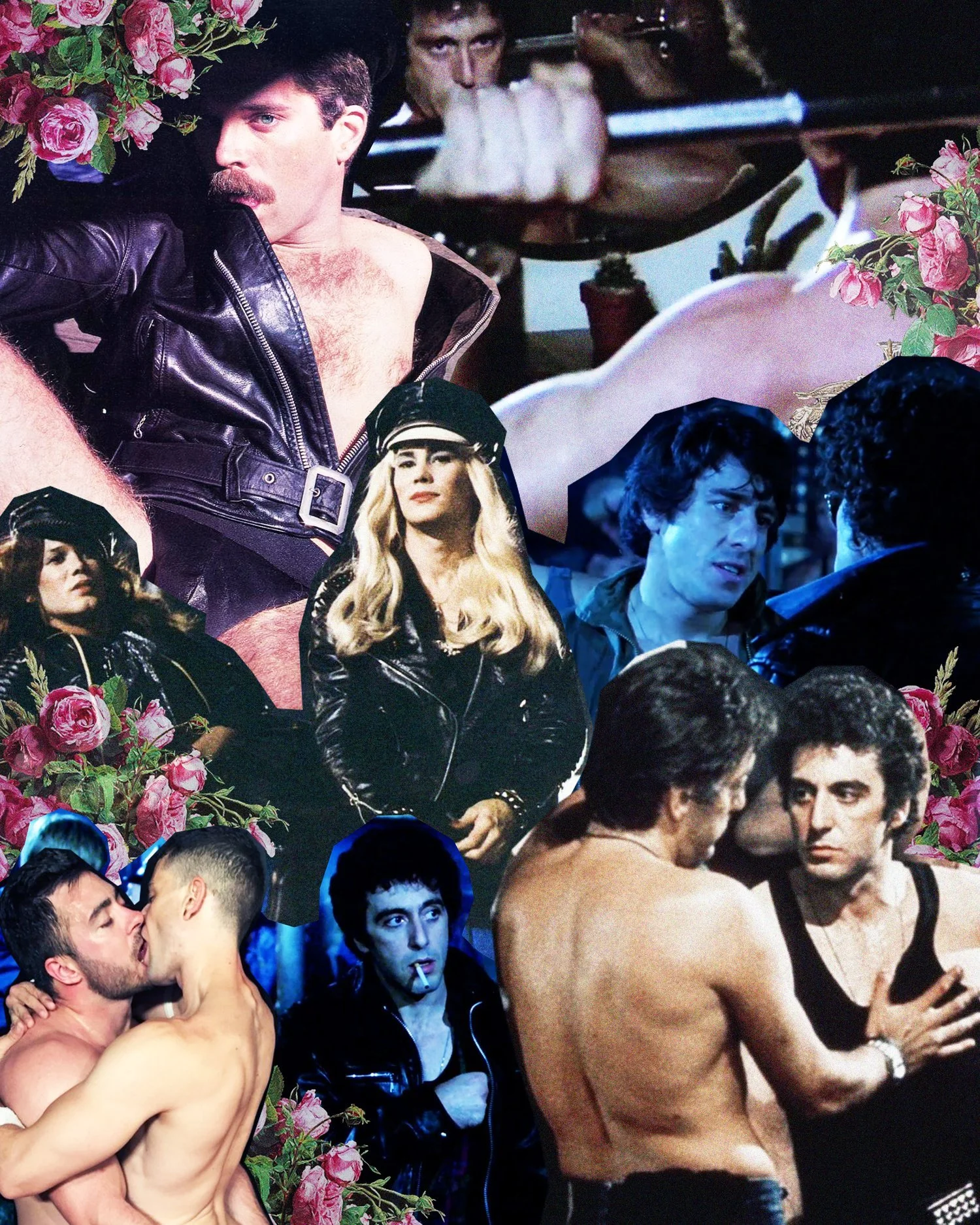

A film that I watched for the first time this year is Yann Gonzalez’s Knife+Heart (Un Cocteau dans le Coeur) from 2018, and it struck me in a similar way. It follows the story of French gay porn director played by Vanessa Paradis in the late 70s as her newest film gets interrupted by a series of grizzly murders of people associated with the studio. It’s like a Dario Argento riff on William Friedkin’s Cruising, a truly modern giallo. In true slasher fashion we get a masked killer with a mysterious back-story, but the design of the killer’s outfit is so good, so unsettling. He wears heavy bondage masks with an incongruous wig over the top of his leather hood, thick gloves and boots, Quentin Crisp’s Great Dark Man fused with Michael Myers. He stalks victims in gay clubs, in dark rooms, in highly charged sexual spaces and wields weapons fused with sex toys. The police are beyond incompetent, they want absolutely nothing to do with the deaths of queer people. They wash their hands of everything. Isolation. The death-by-dildo scene in its opening sequence truly is the missing link between the Lust murder in Fincher’s Se7en and Joy’s fight sequence in Daniels’ Everything Everywhere All At Once. The blood is lurid, the sex is free-flowing and the film grain is authentic.

The connection between sex and violence is inherent, but instead of it being purely for the pleasure of spills and thrills, it becomes an artistic exercise in human effluent and meta-naratives. The spectre of AIDs looms over the dramatically-lit torture of sex workers, porn stars and their adjacent friends in the form of a knife wielding maniac - a seemingly unstoppable force that will not rest until everyone is gone. At certain points it seems the film is taking a supernatural turn, we as the audience start to question whether this killer is flesh and blood, or some hellish punishment. Vanessa Paradis tracks the murderer to a rural village where young gay boys were murdered and the mystique really ratchets up. Crow feathers as talismans. A silent woman haunting the graveyard. Maybe if the spirits can be laid to rest, the killings will stop?

It reminds me of how gay men at the beginning of the AIDs epidemic started creating their own methods of prevention, rituals to ward off the evil illness. If you trace an evil back to its source, it can be reasoned with and defeated, right? That’s how narratives work. “The good end happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what fiction means.” It was once thought that spit would kill the virus, so sucking dick could neutralise an otherwise threatening encounter. Salvation through saliva.

The finale happens in a dark room, a sex space for gay men, and, like the fiction that it is, gives us an empowering denouement. The queer men who have been a hunted class throughout the runtime are able to band together to defeat the evil that threatens them, literally shining lights into the shadowy corners of their sexual mysteries and chasing out the intruder. A community bound together by violence and fear organise themselves and rise up against those that would do them harm. But does violence beget violence? The cycle was started by the murder of gay youth (both literal and metaphoric), so will it continue, or is it justified revenge? The 1980 film Cruising has an interesting take on this idea.

I've mentioned Cruising several times throughout this column so far, and its because I think it is a really interesting and important piece of queer history and media. Cruising was directed by William Friedkin and stars Al Pacino as an undercover cop who has to infiltrate the New York leather scene to find a killer targeting gay men. The film had a troubled production with protests from gay rights groups unhappy with the unsavoury depiction of queer men and its focus on sex and violence. Gay bars banned anyone from the production, distracting lights were shone on the set from nearby rooftops and much of the sound had to be dubbed in the studio because of the noise of street protests. Looking at it now in 2022, I see it as a time capsule of pre-AIDs New York. The scenes in the bars in particular are far more daring and explicit than expected for the time and I think it authentically captures the feeling of coming into a scene you are unfamiliar with, the awkwardness, the excitement, the pretence. Pacino’s character embarks on a journey through this extreme nightlife to find the truth about a killer, but in fact explores parts of himself not previously known. This performance is subtle, ambiguous, with lots of unanswered questions. It is very refreshing when in a lot of American cinema, every plot point is underlined so that an audience doesn’t miss it.

Here, the sex is violent. Bondage, sadomasochism, bulging muscles, chains, straps, nudity, it all comes together in a throbbing sea of sweat and bodies, culminating in one of the herd being led away for the slaughter. These hypnotic club sequences inspired the highly strange James Franco project Interior: Leather Bar, in which he hypothesises what might have been on the 45 minutes of cut and subsequently lost footage excised by the studio (thrown in with a homophobe-sees-the-light storyline that was very false and unnecessary). The narrative is straightforward, but the finale is ambiguous. There is no final unmasking of the killer, there seem to be multiples, maybe Pacino himself is one of them. Maybe the desire to kill is being shared from killer to killer, a murderous sexually transmitted infection that pre-dates the insidious It Follows by several decades. Violent love begets violent ends.

The film was released in 1980, which means it was in production in the late 70s, just as AIDs was beginning to rear its head, so whilst it wasn’t necessarily alluding to it, it seemed to capture some of the frenetic anarchism that was so abundant at its genesis. We know now that AIDs is not a gay killer stalking queer nightclubs and movie sets exclusively. No, in this modern era it wouldn’t be personified as a masked murderer indulging in degenerate desires, but rather as a maliciously negligent bureaucrat who sees no value in ending suffering until it affects his own world. The true horror isn’t the angry spirit seeking vengeance, but institutions that consistently fail us as queer people, people of colour, the working class, disabled, any marginalised community in need of support.

Horror can be a safe space for queer people, because what has so often been the nightmares of the white Christian heteropatriarchy has been the direct liberation of the peoples they oppress. Gay Horror comes from our history, the violence we face and the crises inflicted on us by a malignant hegemony of capitalist conservatives. Gay Horror comes from isolation. Both are real. Both are engaging. Both have the potential to inspire us to rise up before it’s too late. The Revolution is my boyfriend.

Words and Collages: Misha MN