Chris Kraus on Personal Writing, Being Motivated By Desire and Remaining Present

Words: Lia Quezada

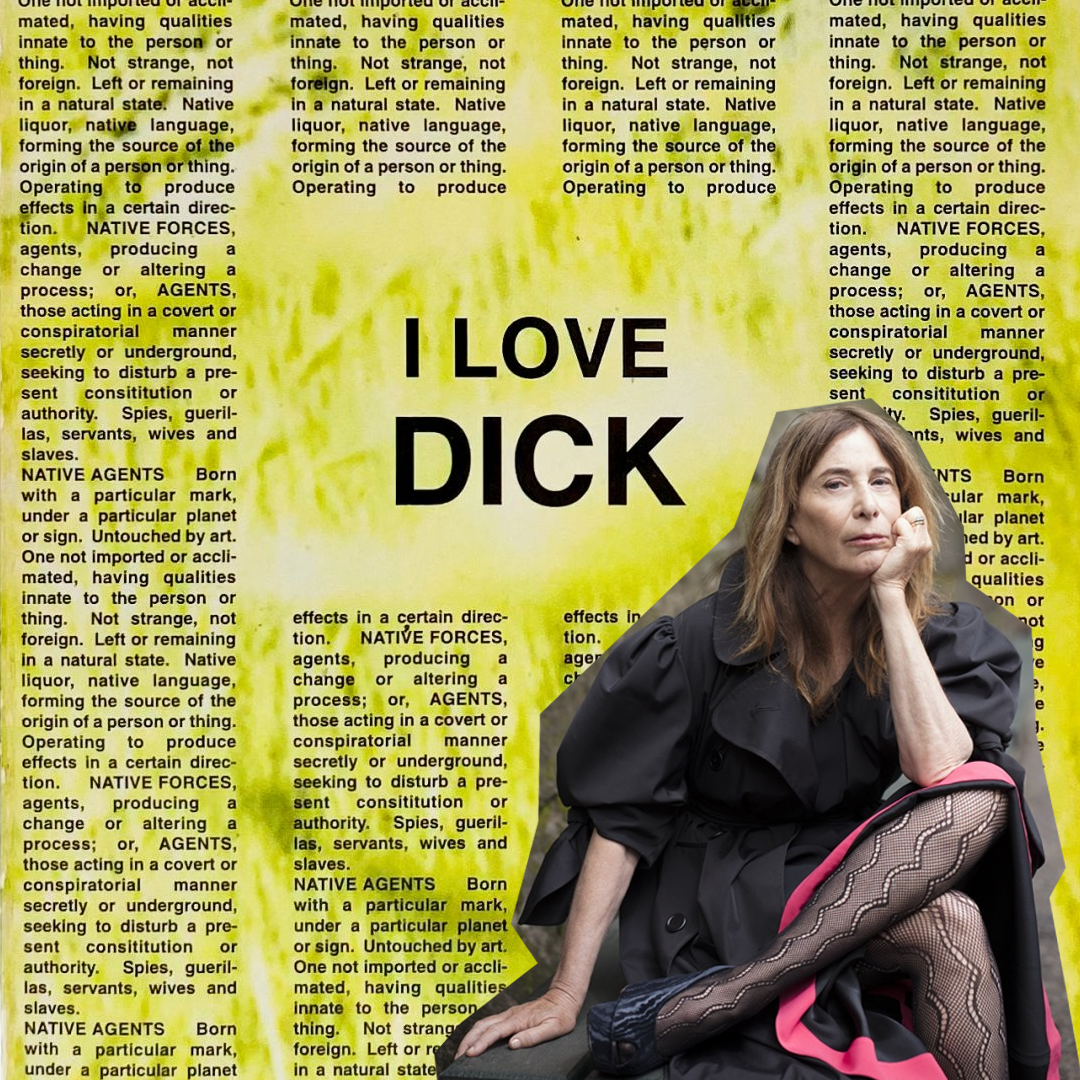

Make it stand out

I wave from the car. Chris Kraus is wearing a colorful bandana and waving back at me. As soon as she takes her spot in my passenger seat, she tells me that she went to get prescription glasses at the place downtown that I told her about: “They were ready in an hour!” She took the subway and everything. On our way to our dinner, we talk about Columbia’s Nonfiction program and Jackie Wang’s Alien Daughters Walk Into the Sun. She laughs out loud when she sees that my phone wallpaper is the Julie Becker painting that Semiotext(e) chose for the cover of Little Joy: Selected Stories by Cecilia Pavón.

In a way it is thanks to her that we are together today. Earlier this year, when I read some of my poems at Cecilia’s poetry office in Buenos Aires, she said that she almost exclusively reads books published by Semiotext(e). I scribbled down the name and Googled it in the evening. A few days later, as a birthday gift to myself, I bought two books written by Chris and translated by Cecilia: Tienda de ramos generales Kelly Lake (Cruce Casa Editora, 2017) and Sopor (Eterna Cadencia, 2018).

Since then I’ve rarely read anything not published by Semiotext(e). One soppy morning I wrote an email to Chris telling her how important her work had become to me and expressing my interest in translating a few of her essays around art. After a couple of emails she told me she was coming to Mexico City to pick up some drawings by a friend of hers. “We can meet for a coffee if you're in town those days”, she responded. I screenshotted the message and sent it to my closest friends. “Yes, of course!” I said, “But don’t you want to do a reading?”

Rushing and stumbling, I managed to schedule a reading of her forthcoming book, The Four Spent the Day Together, at the prettiest gallery of Santa María la Ribera, the Vernacular Institute. Jo Ying Pen, the curator, suggested that Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola, poet and visual artist, would be the right person to talk to Chris afterwards.

While we wait for our table to be set, Chris tells me her plans for her short stay in the City. Tomorrow, before the reading at the Vernacular Institute, she’ll visit the Museo de Antropología e Historia. She’d also really like to go to David LaChapelle’s AMOR. We sit across cut glass tableware and order a focaccia to share.

LIA QUEZADA: You introduced the Native Agents series in 1990 as a counterweight to Semiotext(e)’s primarily male and French Foreign Agents series. What’s the relationship between the books you edit and the books you write?

CHRIS KRAUS: It's changed over the years. When I started the Native Agent Series I wasn't a writer yet, I hadn't started writing. All my friends were writers, and I admired them so much: Ann Rower, Eileen Myles, Cookie Mueller. Their work was so important to me. I was extremely influenced by editing their work and I got to know it very well. When I edited Eileen Myles’ book, Not Me… They gave it to me as a typed manuscript because they didn't yet have a computer, so I typed it into a computer myself. And as I was typing it, I really felt Eileen's voice coming into my body. When I finally started writing in 1997 it felt like I already had all these other people's voices inside me. And that helped a lot. David Rattray was also very important and Kathy Acker, she was another spirit guide. My editorial work with Semiotext(e) has changed since then because the series is much more diverse. In 2004, when Hedi El Khoti joined us, Hedi, Sylvère and I edited everything together. Hedi and I still edit the fiction series together, drawn from a much broader spectrum of writers. Hedi has great knowledge of contemporary French and Francophone literature as well as classic gay literature from France in the 70s. He brought in people like Guillaume Dustan, Mathieu Lindon and Hervé Guibert. And more recently, Constance Debré, who's become a great friend. Abdellah Taia, Lauren Elkin, Verónica González Peña. People whose work I love and feel a kinship with. But, I mean –I’m not cannibalizing them anymore, I’m more or less set on my own path now.

“Desire is the great driver, it motivates us. All kinds of desire –not just sex, but ambition, altruism, life energy, all come from a place of desire.”

So you were first influenced by all of them. Editing fuelled your writing.

Yes. It definitely influenced my writing, and enabled it.

I’d dare to say that failure and desire are the most recurring themes in your novels. Do you think they are connected? Why do they hold such an important place for you?

Oh yes, they’re definitely connected. Desire is the great driver, it motivates us. All kinds of desire –not just sex, but ambition, altruism, life energy, all come from a place of desire. And since most of what we do is doomed to fail, 90% of our desires will always be thwarted, they will not succeed. I don’t think you can write about life without writing about failure because it’s so much a part of everyone's life. If you're not failing, you're not trying.

And you're not desiring.

Yeah. I mean... It really bothered me when people picked up on my first two or three books and said “it's all about failure”, as if failure was this abject thing that I was trying to redeem. But I don't think there's anything abject about it at all. It's completely natural. You know, like falling down when you're trying to learn a sport.

You are interested in women’s POV and experience. At the same time, you’ve questioned the expectation for women to think and talk just about femaleness. What have you learnt in between these boundaries?

When I wrote I Love Dick, I guess I was coming from a place of total repression. The culture has changed a lot since then, women are so much more present. Except for the most blue-chip galleries, gender representation in the art world is pretty much equal. I think the greater remaining dividers are class and race. The fight for gender representation has been won by many, many people. My last two novels, Summer of Hate and The Four Spent the Day Together have much more to do with class and race divisions in the U.S.

You're more concerned about those themes now.

Yes. I mean, a writer's job is to be present at the moment, right? And to reflect reality as they see it. The reality that I'm living and witnessing in the U.S. has much more to do with divisions based on race and class.

How do you feel about people calling I Love Dick or your other novels feminist?

That used to piss me off so much because it's just a book. I mean, I personally am a feminist. I'd never say I'm not. I have a whole set of beliefs: feminism, Buddhism… But nobody is going to say, “are you a Buddhist novelist?” It's ridiculous. So why limit the novel to that single concern? That doesn’t happen with men’s writing.

It's so easy to say that most novels written by a woman and about women's experiences are feminist.

When it can be many other things – in fact, it should be the new universal. When I first moved to New York in the late 70s, I worked on a feminist underground newspaper called The Majority Report. I mean, women are the majority: 51%. So why is it always so niche?

I've said before that what makes your art essays so rich is that you're usually a part of or immediately related to the scene that you're writing about. How do you navigate the intersection of personal experience and broader cultural commentary in your work?

I wouldn't be writing about the art if I didn't know the artist, because I'm basically not that interested in art, per se. [Laughter]. I only become interested in it through friendships and relationships with people... My interest in them opened the door to really seeing their work. But it’s not something I’d do spontaneously. I mean, I've never written a negative art review. If I don’t like the work, I wouldn't bother writing about it. And that's, in a way, why I've stopped writing about art so much.

Because, really, the most that the writer can do is kind of act as a publicist for the artist. And I got a little bored with that. When I've written about people's artwork or these art scenes, like in Tiny Creatures or in Social Practices, it's really because I've kind of had one foot in them. I got interested in writing about border art because I've been spending so much time in Baja, on the border, and it felt very wrong to keep going down there without trying to find my peers there. I made a big effort to meet artists and writers in Tijuana and Mexicali and getting to know them and their work has been such an interesting new part of my life, having some access to border culture.

In most of your work, regardless of the genre, you choose to write in the first person. What place do you think the “I” has seen this day and time?

Oh, I’ve abandoned the first person. I used it in I Love Dick and Aliens and Anorexia, but by my third novel, Torpor, I was writing in the third person. I deliberately made the change for that novel.

Why?

I felt like Torpor was so much more personal than I Love Dick. It concerns Sylvère’s history as a child survivor of the Holocaust and how that level of trauma affected our marriage... That was personal in a way I Love Dick never was. I realized I couldn’t go as deeply into it as I wanted to if I used the first person. I needed to turn the characters into puppets or clowns. There were things I could say and ridicule about “Sylvie” and “Jerôme” that I could never say about “Chris” and “Sylvère.”

I think it's a cultural thing, the use of the first person. Nowadays, we're all writing from and about ourselves. Perhaps because of social media, identity and representation have become so central everywhere, including politics. Semiotext(e) books became known, in part, because writers like Cookie Mueller, Kathy Acker and Ann Rower wrote about very intimate and private aspects of their lives, making them public. It was groundbreaking at the time —a new kind of literature. Now we do it every day.

Yes. I think what makes, for example, Constance Debré’s books literary is that her “I” is a persona. She’s not just blah-ing on about everyday stuff, her writing is highly focused and she uses a very conscious, constructed persona. That doesn’t happen on social media, it’s more like people expressing something in the moment. But a literary work is highly constructed, ideally invisibly so.

Your books started being published almost thirty years ago. What has changed since then, in your life and in your writing?

Everything has changed! I'm about to publish my fifth novel in thirty years. That's not a lot. There are people who bang out a novel every two or three years. But for me, every novel has to come from a different place. And it takes me that long to reach that place, in terms of a life-situation, my thinking, the persona that I will adopt.

Because you write so much about your own life too, right?

Yes, it always comes from my life. It's not autobiographical fiction, but my life is the launching point.

Why do you think it's not autobiographical fiction?

Because my character is not the central character, necessarily. Torpor was as much about Jerôme as it was about Sylvie. Summer of Hate was really about Paul. I put all the BDSM stuff to hook my art world readers who wouldn’t otherwise be so interested in a book about prisons in the U.S. southwest. My goal is to enter the world of the people that I'm writing about. This was difficult with the new book, trying to enter the world of “white trash” teenagers in northern Minnesota. It’s not just the age gap, it’s a complete gap in culture and education. Accessing their state of mind was very hard, but I tried to do that by meeting their friends and their families, visiting them in prison, talking to teachers, social workers, police... Putting together all the conditions that shape their lives as they are. I want to write about other people’s lives as they see their own lives, from their points of view, not mine.