Carolina Falkholt, Consent in Art and If Trigger Warnings Actually Help Us

Content Warning: This piece speaks explicitly about sexual assault

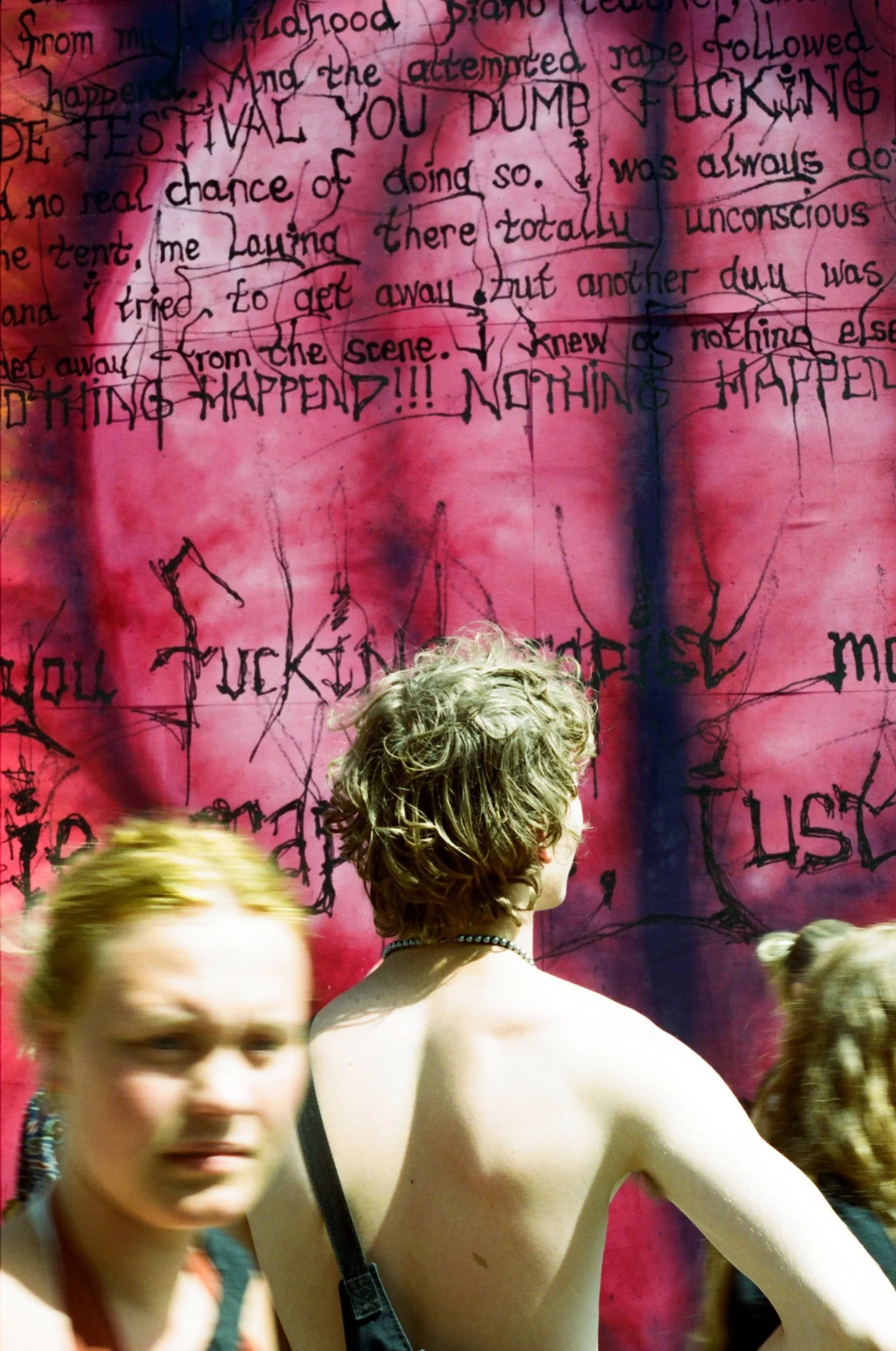

Carolina Falkholt’s mural at Roskilde festival this summer put on centre stage what is often the subject of a network of whispers – sexual assault. Featuring the largest vulva I’ve ever seen covered in a testimony of Falkholt’s own experience of sexual assault at the festival this work unavoidably confronts the issue:

“When I was 17 years old five guys decided to drug me and tried to rape me in my tent at the Roskilde festival. Afterwards, I destroyed the tent with silver paint. I had borrowed the tent from my childhood piano teacher and I felt so ashamed for not returning the tent to him. And he got a bit pissed at me too for that I think. But I just could not tell anyone what really happened. And the attempted rape followed me around for decades. Like a bad curse. Random people I met said things like hahahah YOU FUCKED FIVE GUYS IN A TENT AT THE ROSKILDE FESTIVAL YOU DUMB FUCKING WHORE! Did you not you HORNY NASTY SLUT! The word went around defining me and making me feel immensely ashamed. I was trying to own up to it but I always had no real chance of doing so. I was always going to be the hoe who let five guys fuck me in the tent at the Roskilde Festival. It wasn’t until a friend from that time told me that a passer-by had seen when he peaked into the tent. Me laying there totally unconscious and the guys taking turns on fucking me. That it was an assault and there had been a witness. Up until today I can’t remember anything else than waking up seeing one of the guys pulling his dick out to fuck me and I tried to get away but another guy was holding me down whispering in my ear that everything was alright. I was paralysed but I somehow managed to fight myself out of his grip and ran away from the tent. I ran out without any pants or clothes on in the darkness just to get away from the scene. I knew of nothing else to do, I was totally terrified. Another guy that I knew a little bit ran after me and while I was still running fucked up on whatever they drugged me with, all he kept saying was NOTHING HAPPENED! NOTHING HAPPENED 2 U! But I didn’t want to stop. Not then. Not now. Not ever.”

“Fuck all you fucking rapist motherfuckers in the brain. Die rapists just fucking die.”

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

In contrast to the hushed discussions between women of men to avoid, the power of this work is in its unavoidability. Falkholt’s subject of assault was not hidden in the minds of people who experience it. Instead, it was placed in a public thoroughfare and forced the general audience, especially men, to confront the fact that sexual assault is more prevalent than we like to admit culturally.

The piece and the conversation I had with Carolina about her work reminded me of Virginie Despentes' argument in King Kong Theory, that rape ‘happens all the time. Rape as a unifying act, one that connects every social class and age group, every type of beauty in every personality” - building on Camille Paglia’s statement that rape is an inevitable risk for women who want to go outside and move freely.

“So, while it's shocking to hear someone say so boldly that rape is an inevitable risk for a free woman, I also don’t know a single woman without a story of sexual assault.”

Out of their original context these statements alone are shocking and seem to reinforce life under ‘rape culture’ – a society where sexual violence is normalised and played down. Even Despentes admits that she was initially disgusted by Paglia’s statement about the inevitability of assault, but after talking publicly about her own experiences she was met by other women through the network of whispers and began to see an epidemic.

Yet, upon interrogation it’s clear that Despentes and Paglia are not excusing rape culture, they are trying to reflect an accurate depiction of the issue back to society. They are attempting to shift our conceptualisation of assault from the sensationalist understanding that assault is rare, to an understanding of it as commonplace. Even this article has taken months to write because just as I felt ready to confront the topic, another story of unsolicited sexual advances, flashing, non-consensual touching, attempted rape, catcalling poured out of the mouths of the women I love. So, while it's shocking to hear someone say so boldly that rape is an inevitable risk for a free woman, I also don’t know a single woman without a story of sexual assault.

However, creating and displaying work like this does not come easily. After Despentes released her film ‘Baise Moi’, the first film to be banned in France in X years, she noticed that ‘opening the wound’ of her personal experience was subject to more legal control and censorship than her aggressors ever experienced. Censorship has also occurred repeatedly with Falkholt’s work too, with her large-scale murals of genitalia repeatedly painted over. Despite living under a patriarchal culture that breeds a hypersexualisation of women, we’re unable to address the reality of sex even in its simplest form as genitalia. This aversion to reality becomes even stronger when artworks begin to address the social dynamics around sex.

Talking about the testimony, Carolina said that while she wrote it, “It could have been taken from a lot of women also, because countless women have been through this. So, I just thought putting my story out there would inspire others to also put their story out there and not feel so ashamed of it.”. She went on to say that she couldn’t speak about the event for over a decade because she felt ashamed and that it was her fault so instead, she buried it hoping it would go away. Yet, with the Roskilde commission, Carolina realised that she wanted to talk about the assault in the place it occurred because it had been “such a big, ugly part” of her life, adding that she thought she was not the only one to experience this at a festival. In the UK 34 percent of women reported that they’d experienced sexual harassment at a festival in the previous year with 9 percent saying that they had been assault and its estimated that 250,000 women are sexually assaulted at festivals each year (source).

Carolina’s work presented the organisers with a dilemma. While the power of the mural lies in its honesty and unavoidability for the general audience, there was also an understanding by the organisers that “testimonies can be both re-traumatizing and abusive to others if they are presented in a context where they are met unprepared.” They added that “We recognise the activist idea and know and understand the importance of giving a testimony. On the other hand, the testimony on the front of the Gloria building is explicit and large-scale and hard to avoid if you move about in the surrounding areas. We have no desire to cover up the fact that abuse, regrettably, can take place at the festival. On the contrary, we have been transparent about this for many years and worked hard on preventing it.” This points to a larger question of how do we talk enough about how widespread sexual assault is, while also being mindful of the mental health of those who have experienced it.

When I asked Carolina how she felt about the controversy surrounding her work she commented: “This is more psychological trauma, it's different and I don’t know how to handle that too. But I understood when the curators told me that it's dangerous work and it might make people feel bad. I understand that but it’s also like a lot of artworks might make people feel bad because it addresses different topics.” Recent psychological studies between 2018 and 2021 have presented consistent data about the success of trigger warnings finding that they do not seem to lessen negative reactions to sensitive materials by trauma survivors/those with PTSD, some studies even found that individuals who receive trigger warnings experience more distress than those who did not since trigger warnings reinforce the belief that trauma is central to one’s identity which in turn predicts more severe PTSD (Jones, Bellet and McNally 2020).

When asked about reframing ‘trigger warnings’ as ‘content warnings’ Bellet said that “what really matters is not so much what you’re calling it as what you’re insinuating about a reaction.” Despite the criticism that the shift to content warnings from trigger warnings is purely semantic, I think that it is significant. Content warnings come from a more neutral position outlining the subject of the work in comparison to trigger warnings that assume a certain reaction, thus reinforcing the belief that trauma is central to one’s identity leading to more severe PTSD.

Despentes argument about the ubiquity of rape and it being ‘no longer something to deny, something to be crushed by, but something to live with’ seems at first a surrender to patriarchal society however in combination with this recent research about PTSD it is instead pointing to an alternative future. This is still a difficult argument to make though since it lies close to normalisation of assault, however forging an understanding of sexual assault that both empahsises the ubiquity of assualt and the plurality of reactions to it moves us closer to a better future.

“There was almost a relief to see this inner fury reflected back at me by another woman, a thread of solidarity tying us together.”

But by removing the power of assault as something to be crushed by, it reduces its potential for long term harm. An approach that recognises the plurality of victims/survivors reactions removes the existing expectation of how they should feel and instead opens up space for them to express how they are actually feeling. In turn framing the experience of sexual assualt as ubiquitous helps to break down the indivudalised blame, shame and guilt that victims/survivors feel. Addressing the ubiquity of assault also prevents victims burying their trauma for decades allowing victims/survivors to get more immediate help in the aftermath of their experience and reduce the risk of the trauma being driven deep into the psyche of the victim/survivor leading to more severe cases of PTSD. With a third of women at festivals experiencing sexual harassment its clear that sexualt assualt and harassment must be viewed through a ubiquitous and commonplace lense as this sensationlist lens we currently live under is failing to show the issue honestly and you can’t tackle an issue properly without understanding the nature of an issue.

Encountering Carolina’s work as Roskilde was the first time I felt like I saw a visual representation of the sadness and the fury of existing as a woman in a world where this is commonplace. There was almost a relief to see this inner fury reflected back at me by another woman, a thread of solidarity tying us together. Rather than pushing a narrative of brokenness or irrecoverability Carolina and Virginie create a space to put this anger.

So when the inevitable next episode of sexual harassment happened to me later that summer I thought of Carolina and Virginie and I told the women I needed to. Not to avenge the perpetrator and certainly not to take on an ultimately futile legal battle for this ‘fineable offence’ but simply to help me process it all and stop it clinging to my being. Now this recent episode of harassment has joined the ranks of the cumulative and constant costs/trauma of being a free woman in the world. But rather than crushing me, it’s been processed and is something to be lived with - which is pragmatically probably the best outcome I can have until society is ready to address sexual assault/harassment as it is, rather than how we imagine it to be.

Words and Photos: Issey Gladston