Art Rookie: Reimagining Black Histories and Stories: Lubaina Himid At The Tate Modern

It feels odd to write about an exhibition a few days before it closes. It made me reevaluate why I'm writing about the show in the first place. What purpose does it serve, and why does it matter? I hope these questions don't feel overly pedantic and that there is still space for another essay on Lubaina Himid, whose work has been displayed in the somewhat unsettling industrial-style Blavatnik Building at the Tate Modern since November 2021.

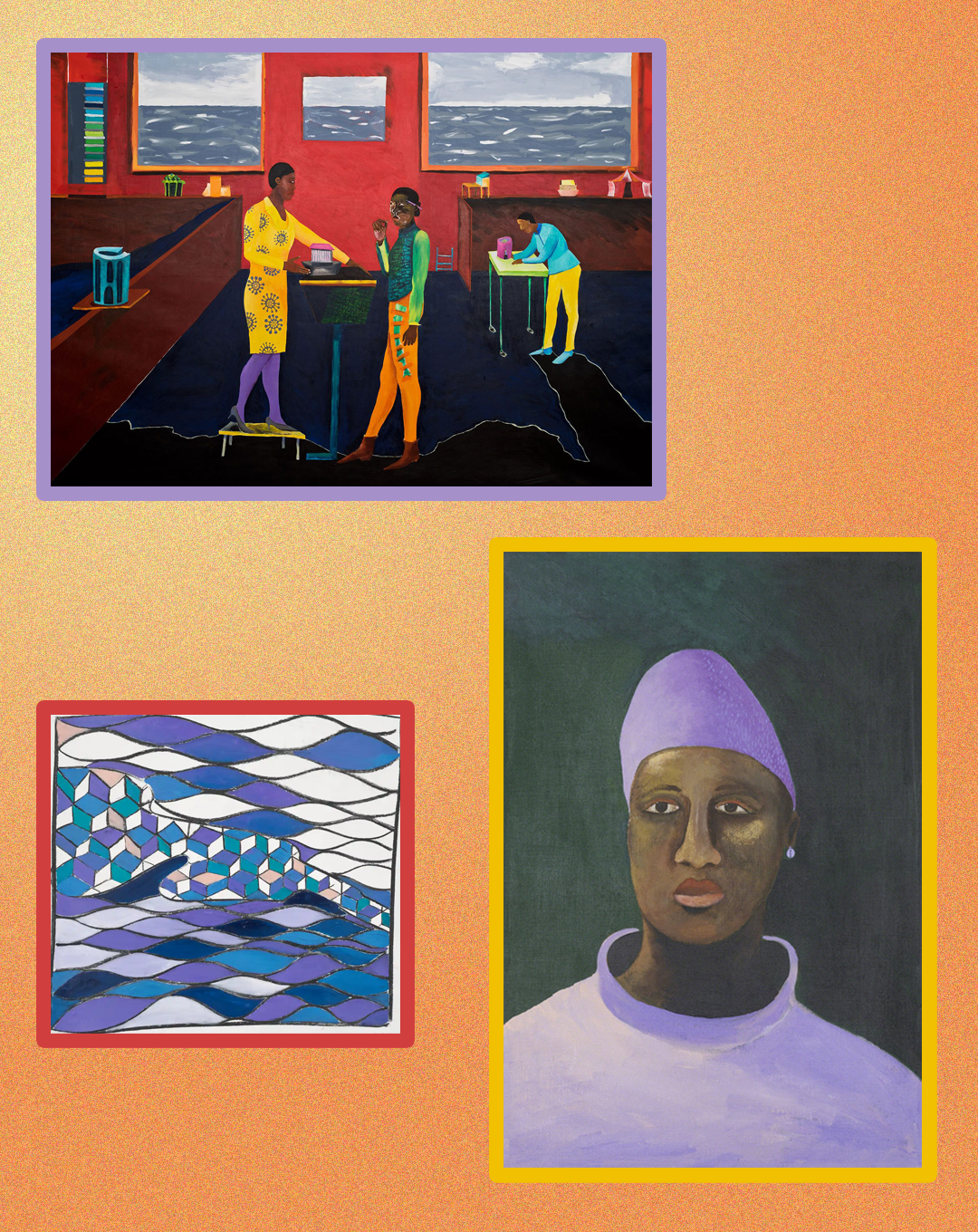

I have been a fan of Lubaina and her whimsical paintings since I started university, and the obsession has only grown since I finally saw them in the flesh at her show at the Tate Modern last week. Born in Zanzibar, Lubaiana was brought to London when she was four months old; it is in London where she began her artistic practice. She played a crucial role in the British Black arts movement that began in the 80s, championing the work of underrepresented artists through exhibitions.

Typically a keen bean rushing to exhibitions before I can read other people's opinions on them; my pilgrimage to the Tate was severely delayed. I will consciously avoid writing about the show at length. Instead, this baby essay will detail the stories Lubaina hopes to share through her artistic practice. If you haven't had a chance to visit the exhibition or haven’t known of Lubaina extensively before, I hope this will urge you to simmer in the chromatic paintings and satirical cut-outs this artist is revered for.

I am conscious of my thoughts and feelings when I visit a gallery. I try and often fail to immerse myself in work without letting the press release dictate what I think. I have started playing a game I heard about on Instagram to help take the pressure off - I pick out the painting or photograph that perplexes me the most and try to sell it to the person I dragged with me to the show. I wax poetic about the composition, the intensity of the brush strokes, and the profound significance of the lavender hues punctuating the piece. I've found this to be an extremely fun, if not an equally cringey, way to experience a show. At the Tate Modern, however, I had a solo day mapped out and selling paintings to myself in my head didn't feel like an appealing exercise. When I walked into the deep magenta hallway wrapped around the words ‘Our kisses are petals, our tongues caress the bloom', I wished I could pitch the entrance to a pal in all my Selling Sunset glory.

Fortunately, Lubiana's show encouraged active participation- 'Audiences as Performers'. No exhibition companion required. The walls are covered with questions, urging visitors to consider the purpose of the paintings beyond their aesthetic qualities. 'What Does Love Sound Like?', 'What Is The Strategy', 'We Live In Clothes, We Live in Buildings-Do They Fit Us', 'How Do You Distinguish Safety From Danger'. They open a dialogue like many of Lubaina's work does on the stories and histories ignored in a white art world.

The tableau of cut-outs from 1986 titled, A Fashionable Marriage, was a personal highlight of the show and depicted art world greed in Thatcher's England. These cut-out figures in regency-era gowns and trousers were placed near disfigured Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagen cut-outs depicted as the adulterous countess and her lover, Silvertongue, from William Hogarth's painting series that inspired the installation- Marriage A-la-Mode.

When I arrive at the final gallery, I make a bee-line to her recent series of paintings from 2016 titled 'Le Rodeur'. These paintings that centre on the tragic 1819 journey of a French slave ship of the same name are an attempt to educate and remind us of the evil legacies of the empire. The majority of occupants on the ship were affected by an incurable illness that turned them blind. For an insurance payout, the enslaved West Africans were thrown overboard.

The Rodeur painting series reflects Lubaina's inclination to "express the joy of making, imagining — the survivor's tale — rather than describe atrocity". Following this message, Le Rodeur features sombre and elegant characters in crisp coats.

“Her work asks us, guides us, and nurtures us. Most importantly, it demands that we radically rethink the world we live in.”

For the Artspace, she shares, 'I keep trying to get to the bottom of this question of how much past historical trauma is vibrating around, say, the buildings that were built with the wealth of that time. That atmosphere lingers. What does it do to us as protagonists within those spaces?'.

Lubaina's concern about showing her work in colonial structures that uphold white bourgeois hierarchies isn't unfounded. This is the same Tate built from the wealth generated from Britain's slave economy, where slave owners donated the paintings on the wall. Tate Britain also holds a racist mural called "The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats," by Rex Whistler, in the restaurant named after the artist they have been resisting removing since 2019. It is now being shown in conjunction with a contemporary artist's work that will, according to the museum's website, be "exhibited alongside and in dialogue with the mural, reframing the way the space is experienced." This lukewarm response from the gallery is no surprise and only goes to show how much we lose by allowing art institutions to be free from conversations on white supremacy.

Lubaina's monographic exhibition at the Tate comes at a time when representation in the arts is more a marketing tactic than accountability. She joins other artists such as Steve McQueen and Zanele Muholi, who the museum group is now championing through individual shows. This focus on inclusion doubles up as a smoke screen from the racist legacies of art galleries in the UK that continue to benefit heavily from donors and artists linked to the Atlantic slave trade.

Even with all these complications and nuances and half-knowing that the Tate’s commission comes from a place of representative politics. Lubaina’s show was transporative. Her work is profoundly engaging and sometimes veers on the satirical; her heightened chromatic paintings reflect her intense subject matter. I believe she is trying to change how we understand and learn history. A worthwhile pursuit that is slowly gaining momentum on social media through projects such as Free Black Uni and FOMO that aim to decolonise education and offer free, accessible resources on British history with an emphasis on the parts of the country's political and social history that is largely ignored by secondary education.

These programmes and Lubaina's work encourage us to reconsider our understanding of history, prompting a discussion on how it is shaped by the stories and narratives we share, the questions we ask and the images we make. Lubaina's work has always referenced the violent relationship between the past and the present. She continually references the legacies of empire and slavery in her paintings, installations and cut-outs. Her work asks us, guides us, and nurtures us. Most importantly, it demands that we radically rethink the world we live in.

Words: Zara Aftab