A Wild and Passionate Uproar: Nan Goldin’s Life and Work in New Laura Poitras Documentary

Ten years old. Five words on the spine of a heavy rectangular book.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

Sex, I thought. This should be good.

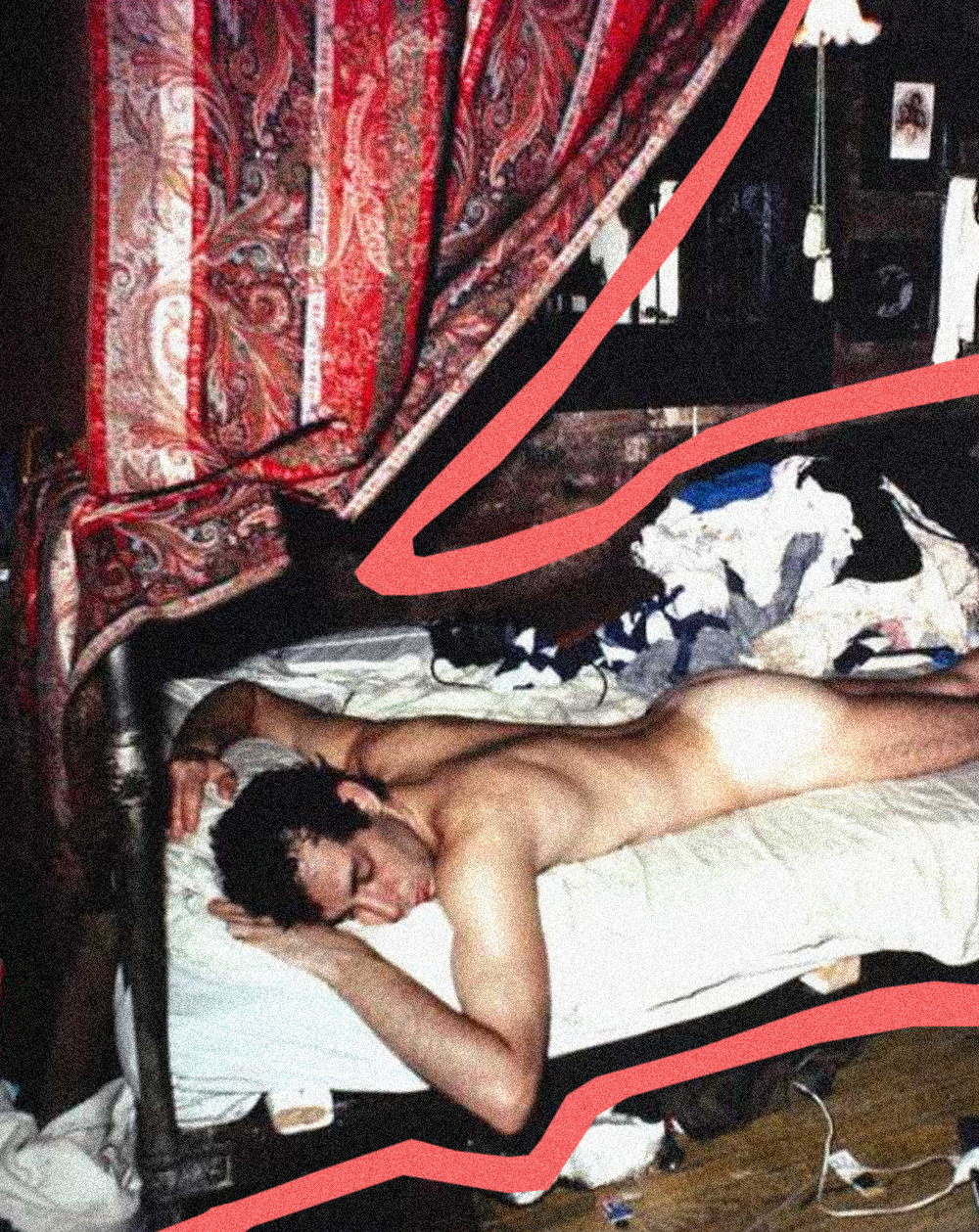

The photo that I flipped to wasn’t explicit but it was intimate. A young man sleeps nude on his stomach, ankles crossed. His room is so so messy. Off white clothes in heaps on the bed, on the floor, tumbling from shelves. Piles of books and records. On the wall is a family portrait above a photograph of a cow. A pair of elegant white opera gloves are neatly folded on the bed frame. I wanted to catalog the items to discover where the sleeping man had come from, what his dreams were.

The title was blunt: Kenny in his room, NYC, 1979.

Kenny’s portrait was my introduction to the work of Nan Goldin, an American photographer and activist who gained recognition in the 1980s for documenting the lives of herself and her friends in the queer party scenes of New York and Boston. Her photographs brought the everyday lives of communities many thought to be illegitimate into museums and prominent galleries as stunning visual explorations of intimacy, sexuality and power.

Goldin is the subject of the new film, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, directed by Laura Poitras. Moving between two timelines, the film follows Goldin through her early years developing her artistic voice in urban bohemia while also tracing her recent activism around the opioid epidemic. In covering such vast thematic territory the film occasionally falters in narrative concentration especially in the modern day sections. Nevertheless, Poitras’ skill at subtly connecting themes throughout Goldin’s varied experiences grounds the film as a moving meditation on photography, friendship and the importance of bearing witness.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Long before Goldin received critical recognition, she showed her photographs as slideshows in the clubs of downtown New York. The rowdy audience who gathered to watch was filled with the friends who were the subjects of her pictures. Over Goldin’s bootleg soundtrack, they would cheer or heckle depending on whether they liked the images of themselves. Goldin would edit her slideshow based on the crowd's reaction and replace and rearrange slides for the next time she showed it.

The slideshow format shaped Goldin's distinct visual style. She found she could bring out various themes in her photographs depending on how the images were juxtaposed. The lives of the people she photographed didn’t stop once the photo was taken and she resisted stasis in her images to mirror this complexity. Her photos convey humor, danger, lust, jealousy, tenderness and violence all at the same time. It’s slice of life photography taut with narrative tension.

Poitras makes use of large portions of the iconic slideshows in the film layered with thoughtfully excerpted interviews in Goldin’s dry, quick-witted voiceover. In one such section we see a series of portraits featuring Cookie Mueller, writer, actress, New York personality and longtime friend of Goldin’s. Over decades of Goldin’s work, Cookie beams in the arms of her girlfriend in sunny Provincetown, laughs uproariously in a New York night club, and dries her tears with white lace at the altar on her wedding day.

Poitras is not interested in babying her viewers.

The tender 1989 portrait, Sharon with Cookie on the bed, Provincetown, has a more somber mood. In it, Cookie turns her head towards a beam of natural light out of the frame. Her ex girl-friend, Sharon, sits a few feet away. Between them hangs a photo that Goldin herself took of Cookie with her husband, Vittorio Scarpati, on their wedding day. The room is bathed in dense purples and shadows.

In voiceover, Goldin explains that the portrait was taken shortly after the untimely death of Scarpati from AIDS. Sharon, years after her and Cookie were romantic partners, had moved in to provide care in the final months before Cookie too succumbed to the virus. Their faces are older and less carefree than when we met them embracing as lovers on the beach. The wedding photo between them is a stark reminder of time passed. But the undeniable care and tenderness between the two women endures, deep and unwavering.

A less confident documentarian might deploy a troop of talking heads to spell out the poignancy of Goldin’s work but Poitras is not interested in babying her viewers. Instead she allows the audience to experience the unique ability of Goldin’s images, beautiful on their own, to deliver their strongest emotional punch as shifting moments within the ongoing narrative of a complex life.

The modern day timeline of the film follows Goldin’s efforts to hold the art world accountable for accepting huge sums of money from the Sackler family, well known philanthropists and patrons of the arts. Until recently, the Sacklers were less well known as the owners of Purdue Pharma, the pharmaceutical company that made and distributed the highly addictive painkiller, OxyContin. Under the Sacklers, Purdue launched a multifaceted campaign that misinformed the medical community about the risks of Oxycontin and incentivized doctors to prescribe it. Even as the United States reeled from a full-blown opioid epidemic, Purdue reformulated OxyContin in order to maintain sole control over its production and continued to insist that the only problem was irresponsible drug users giving their product a bad rap. The family name graced wings in the Met, the Louvre, the Tate and the Guggenheim, yet their fortune was earned with the price tag of millions of Americans suffering and dying from opioid addiction.

Goldin herself became a victim to the Sacklers’ relentless marketing of OxyContin. Although she took painkillers as prescribed after a wrist surgery, Goldin found herself increasingly dependent on the pills until, as she describes in the film, “my life revolved entirely around getting Oxy.” After a near lethal overdose and heroic recovery, Goldin founded PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) an activist organization to respond to the opioid epidemic by targeting big Pharma and raising awareness about harm reduction models of addiction treatment.

In the film Goldin, arm in arm with fellow activists, throws pill bottles into the reflecting pool at the Met, blankets the Guggenheim in swirling prescription notes and wades chanting into the Louvre fountain. Modern day protests are juxtaposed with archival footage of ACT UP, drawing clear parallels between the radical protests strategies pioneered by many of Goldin’s closest friends and collaborators in the 1980s and 1990s with PAIN’s tactics to bring attention to the hypocrisy of the Sacklers.

While considerable care was taken in the past timeline of the film to paint a clear picture of Goldin’s community and the personalities in her life, this effort is somewhat dropped in the present day timeline. It is explained that PAIN is made up of activists who are themselves survivors of opioid addiction or have relatives who have been affected but there is minimal screen time devoted to fleshing out any of their personalities or backstories.

Despite its less personal tone, the Sackler storyline has some truly moving moments that sharply humanize the opioid epidemic. As I left the theater there was one in particular that replayed in my head. Early in the film PAIN organizers are crowded into Goldin’s New York apartment to discuss the museum protests. Activists are sprawled on couch cushions, leaning against door frames, crouching on the floor. They talk urgently but there is comfort and camaraderie between them, often laughter. Someone finds a fluttering moth trapped inside the house and everyone becomes focused on ushering it out the kitchen window. There are cheers when it finally flies free into the blue night. The moment was fleeting and fragile but somehow it summed up everything.

Words: Evelyn Burke